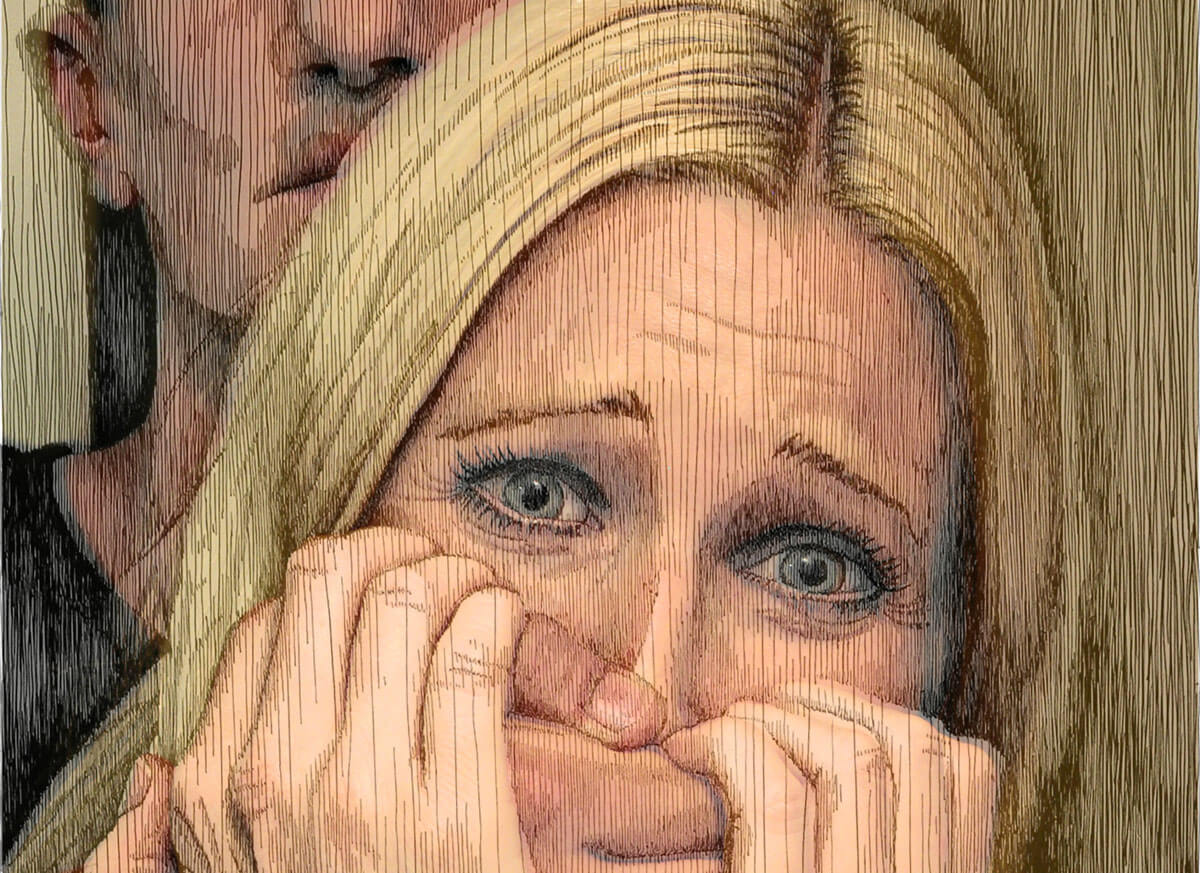

On an unseasonably cool September night, a 16-year-old girl with a Kewpie doll face, curly brown locks and hazel eyes sat in the kitchen of her mother’s spacious single-family home inside a gated community in western Broward County. After finishing her math homework, Chloe grabbed a snack out of the stainless-steel refrigerator, quietly packed her book bag with some personal belongings and sneaked out to meet a girl from school.

It was more than a year before she returned home.

Compared to many of her friends, Chloe (whose real name is being protected by Lifestyle because of the nature of her story) already had dealt with her share of drama. Her mother, a native of Haiti, fell apart after Chloe’s stepfather died. Chloe had to be shuffled between family members; she even spent time in foster care.

Still, by the start of her junior year of high school, things had improved. Chloe was back home with her mother, a businesswoman who had just earned her third college degree. She was making straight-A’s in school, enjoyed an active social life and lived in a beautiful home—which is why what happened that night took everyone, including Chloe, by surprise.

After she sneaked out, her friend drove her to meet a man “who had a clothing line.” She told Chloe that the man could help her pay for college, that he would give her a car—whatever she wanted. Chloe was intrigued.

“She took me to this huge house with a pool and marble floors,” Chloe says. The man “came out in a robe like Hugh Hefner. Then a girl who lived there, and who looked like a Playboy Bunny, came in and handed him $1,000 from her night’s work.”

The man sat with Chloe and asked about her life. More important to her, he listened. No one ever listened to her. He told her the people who lived in the house were like family, that many of them had come from abusive homes. He told her he understood how difficult parents could be. He really did understand her. He told her how special she was when he had sex with her. No one ever complimented her.

What he didn’t tell her was that he was a sex trafficker.

Chloe, the honor student from a solid middle-class home in Broward, soon was working as a dancer at a local strip club. The man in the robe was now her pimp. Before long, he transitioned her into prostitution.

“You don’t have to be uneducated to become a victim of human trafficking,” Chloe says. “I didn’t even know I was a victim. I didn’t think I was being forced into prostitution because I was manipulated and brainwashed. [Even] if my family had tried to take me out of there, they would have lost me and I would have taken his side.”

As hard as it may be to believe, Chloe isn’t alone. She’s one of the new targets being lured into an age-old criminal enterprise, targets who break with socioeconomic stereotypes. Chloe wasn’t a runaway recruited at a bus station. She wasn’t a troubled teen from a low-income neighborhood. By her own admission, Chloe was happy at that point in her life. Yet, somehow, that wasn’t enough.

“Today, community children, middle-class girls are being trafficked more than runaways or foster and homeless children,” says Jumorrow Johnson, president of the Broward Human Trafficking Coalition and a victim advocate at Florida Atlantic University. “These are kids with family connections, values and morals.”

Today’s sex trafficking doesn’t discriminate based on age, education, gender or class, Johnson adds. Barriers once considered impenetrable—wealth, schooling and upbringing—are now breached with the help of social media, high school “friends” who work as talent groomers, and pimps posing as boyfriends. It’s happening in tony towns, gated communities and seemingly stable homes.

Just ask the parents of Abby.

Preying on Weakness

“It started out very innocently,” says Abby’s mother (Editor’s note: Although her parents spoke on the record for this story, Lifestyle is withholding the entire family’s identity because of the nature of their daughter’s experiences). “She met him at a high school football game, and she started dating him. We met him once when he came to pick her up one night. He was a few years older, he dressed well, and he had a nice demeanor.

“But something about him made my red flags go up.”

The family lived in a middle-class neighborhood in Plantation; they worked hard to provide a loving, safe environment for their daughter. Abby, 17 at the time, was home-schooled and had never been in trouble. However, things changed after she met “him.”

“You would never think that a girl like her would become a victim of trafficking,” her mom says. “But if community kids aren’t secure with who they are, and they want to ‘fit in’ and be liked, they become an easy target for these animals. The pimps find the weakness in the girls and the family structure, and they prey on it. Our [weakness] was having our barriers and guard down.”

“You would never think that a girl like her would become a victim of trafficking,” her mom says. “But if community kids aren’t secure with who they are, and they want to ‘fit in’ and be liked, they become an easy target for these animals. The pimps find the weakness in the girls and the family structure, and they prey on it. Our [weakness] was having our barriers and guard down.”

Abby’s parents noticed changes in her behavior, the clothes she wore, and the new friends she started hanging out with. One night, her father caught her in a lie and then saw messages on her cellphone from Backpage.com, a classified advertising website that includes “dating” among its categories. Often, those ads are thinly veiled sex-for-money hookups.

He confronted her. She was drunk and told him she “didn’t want to be here,” and she walked out the door.

Abby’s father says his daughter was pretty but gullible, and able to be manipulated.

“He controlled her every move. He kept her in a hotel and didn’t start prostituting her until she was 18,” her dad says. “He gave her attention, gifts, anything she wanted—even though we gave her everything. He ‘groomed her’ until she became his puppet. She did it out of fear and manipulation until she no longer knew who she was.”

Mom had a prayer room in Abby’s closet; every day, she called on a higher power to bring her daughter home. After two years, her prayers were answered. Abby returned, but she wasn’t the same bubbly, high school girl who had walked out. Her identity, it seemed, had been erased. It took six months of intense therapy, but she slowly regained her footing in the world she once knew and loved. Abby is now sober and starting a new life as a flight attendant.

The trafficker who took their daughter is in jail—but Abby’s parents believe she is still emotionally attached to him. On some level, experts say, she might always be.

Behind the Numbers

According to Carmen Pino, special agent in charge of the Department of Homeland Security’s investigations unit in Miami and the head of the federally funded South Florida Human Trafficking Task Force, Florida has the third highest number of reported human trafficking cases, behind Texas and California.

In 2016, the National Human Trafficking Hotline recorded 556 trafficking cases in Florida; 406 of those reports were classified as sex trafficking, an increase in that category of 98 cases compared to 2015—and more than double the number of sex trafficking cases (170) from 2012. In Broward County, 173 allegations of trafficking/sexual exploitation were accepted by the Florida Abuse Hotline between April 2016 and April 2017; 52 of those cases were verified—nearly 20 more than in calendar year 2015.

Part of the recent increase is attributed to traffickers targeting girls from middle-class and even wealthy families. Just how does a popular high school girl from a loving family fall into the clutches of a sex trafficker? How is it possible that a straight-A student doesn’t understand that she’s being forced into prostitution?

“Traffickers look for victims who are vulnerable for many reasons, and not just [related to] economic or social standing,” Pino says. “[It can be] psychological or emotional vulnerability. When someone lacks confidence or has low self-esteem, no matter how much you build them up, they can fall victim to these guys.”

In the case of Chloe, initial contact involved a recruiter, typically someone who blends in to the victims’ social network, such as boys or girls from their high school or teenagers working at a local retail outlet. Recruiters are paid per successful target; they don’t have sex with the pimp, and they’re not prostituted, so they can remain in circulation and replenish the “inventory.”

Captors are equally adept at exploiting their victims’ vulnerabilities through manipulation, deception and seduction. They control targets by isolating them from reality until the victims believe that they’ve made a conscious decision to abandon their friends and family, and that they’re committing sex acts for money, under the age of 18, of their own free will.

Johnson, of the Broward Human Trafficking Coalition, says victims are being “Romeo-pimped”—groomed by traffickers for several months and through distinct phases. This new breed of pimp—no longer content with pursuing dislocated, solitary youth, whose nomadic lifestyle doesn’t allow for a methodical grooming period—increasingly look to higher-value targets.

“People with nothing to lose can’t be controlled, so the traffickers target girls that they can leverage by using threats about their family” or naked photos of the victim that the pimp threatens to release, Johnson says. “It annoys me that people are shocked at what’s happening in their own neighborhoods. But that’s partly because the girls usually don’t come forward—and parents don’t know how to read the signs that their girls are becoming victims.” (See sidebar)

Tricks of the Trade

Traffickers trolling for victims in such waters are adept at staying a step ahead of law enforcement. Authorities admit flushing them out is a challenge. It doesn’t help that some victims decline to cooperate with the police when an arrest is made.

Then there are the hundreds, if not thousands, of cases that either go unreported or are not considered sex-trafficking that the National Human Trafficking statistics for Florida do not take into account. As in many rape cases, victims often are afraid or too embarrassed to come forward. Other victims disconnect with reality and succumb to Stockholm syndrome, a psychological condition in which a person taken hostage sympathizes with or becomes emotionally involved with his or her captors—so much so that they don’t try to escape, don’t report their captors, don’t cooperate with police, and, sometimes, even defend the trafficker in court.

“Sometimes, the [girls] are so traumatized that they don’t even realize they are victims,” Pino says.

Looking back, Chloe can now see the manipulation. She understands that if a parent doesn’t give their daughter a material item, the pimp will give her three. That he plays on targets’ low self-esteem by showering them with praise, complimenting their sexual prowess and putting them on a pedestal—until the pimp takes it all away.

By the time victims realize what’s really happening, it’s too late. They either convince themselves, or allow the pimps to convince them, that they now have a better life. Or, like many, they slowly tumble into a numb trance, disconnected from their own identity; they rely on drugs, alcohol and random sex to cope. Traffickers rarely engage in physical abuse, because they usually don’t have to. Threats and persuasion are their passive-aggressive weapons of choice.

“He dressed nice; he dressed us nice,” Chloe says. “He was a smart, successful rap musician and record producer, and we lived in a fancy house. People should know just because he didn’t look like a stereotypical pimp, and we didn’t look like hookers, that this still wasn’t sick and twisted. I was like a zombie [at a certain point]. He made me take anti-depressants and do drugs. I had two abortions, and I wasn’t allowed to have contact with my family for over a year.

“Being sex-trafficked was not my choice or my fault. Just because I wasn’t kidnapped or beaten doesn’t mean I was there on my own freewill. It’s hard to explain why I was a victim. I’m not a bad person. I had a loving family and lived a good life, but [deep down], I had no self-confidence. I let [the pimp] take everything from me.”

Chloe, who’s now in her 20s, was able to emerge from her ordeal. She’s an advocate for foster care improvement and helps to educate foster children about their rights and benefits. She also mentors young girls who were victims of sex trafficking, using her experience as a teaching tool to help them reclaim their identity and independence.

Today, when she sits in her mother’s kitchen and grabs a snack out of the fridge, there is no thought of sneaking out. Instead, she pulls the textbooks out of her bag and focuses on her studies.

Chloe is in her first year of law school.

Editor’s note: Special thanks to Nelson Hincapie, president and CEO of Voices for Children Foundation in Miami-Dade County, for arranging Lifestyle’s interview with Chloe—and to all the expert sources who spoke to our reporters for this feature.

Warning Signs

Victims of sex trafficking often are so brainwashed or manipulated that they are not aware they’re being victimized, which makes it difficult for friends and family to detect.

“Victims of trafficking don’t always cry for help,” says Jumorrow Johnson, president of the Broward Human Trafficking Coalition. “They feel it’s their fault and are not likely to come forward. They struggle with shame and guilt, especially if they are attached to a reputable family. They develop coping skills that make them not react as expected, and they shut down emotionally.”

Here are some of the signs that your child may be a victim of sex trafficking:

- Injuries, bruises or other signs of physical abuse.

- Unexplained new circle of friends or older acquaintances.

- Branding tattoos that reference money, “Daddy” or a man’s name.

- Controlling “boyfriend” or intimate relationship with an older person who is not age-appropriate.

- Unexplained new items such as cellphones, jewelry and clothing.

- Hiding their computer, phone communications or details of their whereabouts.

- Being a chronic runaway.

- Late night telephone calls, or having multiple phones.

- Isolated and secretive about whereabouts.

- Having a sexually explicit online profile.

- Referencing sexual situations that are not age-appropriate.

- Refers to trafficker/pimp and associates by familial titles such as “Daddy” or “family.”

—Compiled from sharedhope.org and bhtc.us