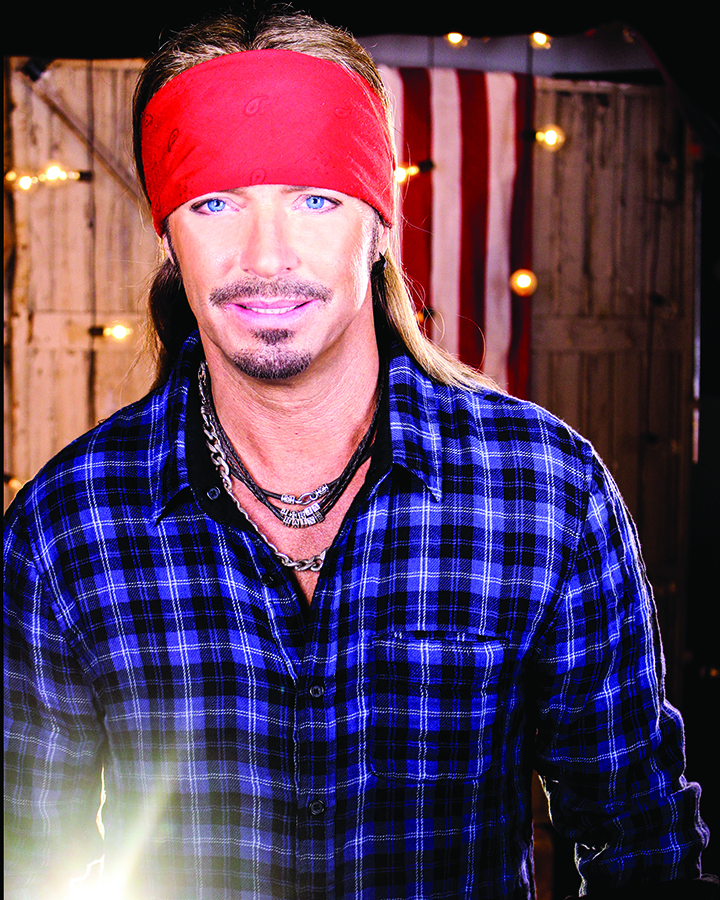

Bret Michaels won’t be working from a set list when it comes to his official duties as grand marshal of the 48th annual Seminole Hard Rock Winterfest Boat Parade (Dec. 14). But the longtime front man for the rock band Poison—and, for the reality generation, star of VH1’s “Rock of Love” dating series (2007 to 2009)—already knows what he’ll be bringing to the show.

“I can tell you this,” says the 56-year-old Michaels, whose rock résumé includes more than 50 million albums sold with Poison and a prolific solo career. “I’m there to help raise the energy of the party level, and to bring awesomeness and fun. So, I believe my duties are to meet a lot of great people, have a great time, and add to the ‘Greatest Show on H2O.’ ”

If Michaels is savoring life a bit more these days, it’s with good reason given his health challenges over the past decade. Last year, Michaels was in and out of emergency rooms for issues related to the type 1 diabetes he’s had since age 6; in 2011, he had surgery for a hole in his heart; and in 2010, Michaels underwent emergency appendectomy surgery—and suffered a massive brain hemorrhage that left him in critical condition.

Through it all, Michaels has maintained the infectious high energy and positive outlook that shine during his live performances—which South Florida fans can catch the night before the boat parade at Hard Rock Live (Dec. 13).

“I’m grateful to get to do what I love to do—which is being on the road and making music,” he says. “The passion is the same and the energy level may actually be better.”

You’ve said that the new song “Unbroken,” which you wrote with your youngest daughter, Jorja Bleu, resonates with both of you for different reasons. In what ways?

You’ve said that the new song “Unbroken,” which you wrote with your youngest daughter, Jorja Bleu, resonates with both of you for different reasons. In what ways?

Jorja is a young spirit and an old soul. She was going through a tough time in her young teenage life. She goes to a school for arts and music—so, I said, ‘Let’s get on the piano.’ I told her how I’ve been through a lot of stuff in my life—and not just the brain hemorrhage and diabetes, but I’ve run up against walls of criticism and harsh words.

You know what? You have to be stronger than the storm. So, why don’t we write something where, in the end, the chorus is powerful and gives people hope. And gives you hope. It’s quite personal, but I also think people relate to finding triumph over tragedy.

Your oldest, Raine, was featured in this year’s Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue (she’s also studying music at Belmont University in Tennessee). How do you reconcile the pride you have for your girls with your protective instincts, knowing what you know about the business?

As fathers, we always say do as we say, not as we did—or do, right? Here’s the thing for me. If there’s one thing I want, it’s to be a good dad. I’m supportive but also very protective. I keep a close eye on them, but at the same time you have to let them learn to fly. They have to learn how to handle stuff that comes at them. What has worked for me is telling the girls to always go with their gut. As a dad, you hope you’ve instilled in them a kind of intuition. If you feel like something isn’t right, it usually isn’t—so react before it goes bad. If Raine is in a situation where she feels uncomfortable, for example, recognize that and deal with it. … At the same time, I also tell her to have fun—you want to enjoy your life and find that balance.

Both girls are really humble, and I’m so proud of both of them. Listen, they’re going to get crazy. But I tell them to just try and make occasionally good decisions in their teenage life.

You had a tight relationship with your father (Wally Sychak), who died this summer at age 85. He served with the U.S. Navy during the Korean War and loved his Pittsburgh teams. What about his example had the most impact on you?

Both my dad and my mom had a strong work ethic. My parents liked having fun—they loved tailgating at Steelers games—but at the same time, they got stuff done. My dad advocated for veterans. My mom helped to form the first diabetic youth camp in our area. Talk was cheap for them. You have to rock the walk.

Their sense of adventure also stays with me. Our summers were getting in the car, driving to Florida, and having the time of our lives along the way. We got to see all the great sights, including Gatorland in Orlando, which I loved. These were big doings, and we enjoyed all of them—and on a budget.

So, what they instilled in me was the journey. That’s the pot of gold.

Did Dad appreciate your music? You don’t think of a Korean War vet when you think of Poison.

When I was kid, my parents knew there were two things I loved—sports and music. On the wood-paneled wall in my bedroom at age 16, I had a poster of Steelers quarterback Terry Bradshaw—flanked by a poster of Jimmy Page from Led Zeppelin.

There was always music on in our house, all kinds, including country and big band. My mom played acoustic guitar, so I’d also hear a little John Denver in the house. But rock always hit my soul. And the rock music I grew up on was diverse—I listened to everything from Rush to AC/DC to Kiss to Yes. There was Jim Croce, Harry Chapin, James Taylor. The beauty of music is that there’s a song for everybody at any given emotional time. Music is the soundtrack of my everyday life.

But getting back to my dad. The first time I played Hersheypark Stadium [in Pennsylvania], he was so blown away—and not just by the show. He was blown away by the amount of road crew and semi-trailer trucks we had. Everybody on the road crew loved my dad. He’d be like, “How does this thing run?” and he’d get up under the hood of the truck and look around.

But he was also like: “You’re my kid. You used to play in our basement. And now you have all these people working with you, and you have eight semi trucks?”

He was proud of all of it.

In your recent interview with Dan Rather, you talked about how being a diabetic not only made you grow up fast, but it was a driving force behind what you would become. Can you unpack some of that?

Being a diabetic is a daily struggle. You have to go twice as far to get half the distance. I accepted the card I was dealt. Five insulin injections a day. That doesn’t mean that I loved it. But it became my backbone. It made me realize that I’m going to have to put my work in as a diabetic. It helped to carve out a never-give-up spirit. To stay in the fight.

With Dan, we talked about the critics’ [reaction to Poison], and I said none of that will ever be as harsh as diabetes is for me. So, it helped me to rise above all that.

Why do you think that the era of metal with Poison took such a critical beating?

I don’t want to speak for other artists, but for me, we lived in sleeping bags behind a dry cleaner for three years. Any odd job we could snag to survive in Los Angeles, we’d take just so we could play original material. We put in our time.

We also liked to put on an incredible show; all of us have this crazy built-up energy. We liked to take what would be considered anger and turn it into a positive force. I think the visible energy threw them off. What the critics also never realized is that they were just adding fuel to my fire. In other words, had they embraced us, I probably wouldn’t have lasted more than one record.

In Australia, you can buy the “unedited” version of “Rock of Love.” Is it safe to say there’s some interesting footage in those DVDs?

“Interesting footage” is the exact way to leave that one.