The Federal Bureau of Investigation honors its fallen on a Wall of Honor at agency headquarters in Washington, D.C., and at field offices around the country. As of 2020, 81 agents and employees who lost their lives in the line of duty had been memorialized.

Two more names soon will be added to the wall in the aftermath of the Feb. 2 shootout in Sunrise that claimed the lives of two FBI agents—Daniel Alfin, 36; and Laura Schwartzenberger, 43—and wounded three others. The incident with a lone gunman, who was being served a court-ordered search warrant for a case involving violent crimes against children, was described as the most violent in FBI history since another South Florida shootout.

That incident, 35 years ago this month, occurred on a residential street behind a shopping center in a part of Miami-Dade County known for its impeccably manicured lawns, grand homes and comfortable level of privacy and safety.

It took only five minutes to set in motion events that would change the South Florida landscape—and forever alter tactics at the FBI and for law enforcement throughout the nation. Similar to the deadly shootout in Sunrise, this one also started early one morning.

Ready and Waiting

Ready and Waiting

April 11, 1986.

Unknown to residents of what was then an unincorporated portion of Miami-Dade County, one of the most well-traveled roads in the area was teeming with members of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Early that morning, Special Agent Gordon McNeill of the Miami FBI, supervisor of a task force intent on stopping a six-month spree of armed bank and armored car robberies, had dispersed 14 agents in 10 unmarked cars to stake out agreed-upon areas covering a nearly six-mile stretch of South Dixie Highway.

The day before, McNeill told fellow Special Agent Benjamin Grogan that he had a hunch.

McNeill wanted his teams in place by 9 a.m.—0900 hours, in FBI speak—on that Friday. Over the course of successful and botched robberies since October 1985, two suspects described by bank workers and armored car couriers had been consistent enough for FBI agents to detect a pattern. They typically struck on Fridays, mostly before noon, and always in the South Dixie Highway area, from Dadeland to Southwest 147th Street. What wasn’t clear was whether the two men were acting alone or were part of a larger gang.

At 9:32 a.m., Grogan alerted the dispatch operator that FBI unit 2960 had a black car under surveillance going north on South Dixie. “We believe it’s the black Chevy we’ve been looking for,” Grogan announced. “Tag number is November-Tango-Juliet 891.”

Grogan, a 25-year veteran, had joined the FBI as a special agent in 1961. His brother, Pat, said that Grogan dreamed of being part of the agency as a boy—yet, his high school years suggested otherwise. After finishing eighth grade, the Georgia native attended a Catholic seminary in Pennsylvania to become a priest. He later taught Latin and biology at Marist College before leaving the priesthood to join the FBI.

This was slated to be Grogan’s final year with the FBI before his retirement.

“Verifying 891,” the dispatcher replied. “It’s got a hold on it for a robbery unit.”

The dispatcher alerted other units in the area of Grogan’s plans to stop the black Chevrolet Monte Carlo and the two men inside. Law enforcement would later identify them as Michael Lee Platt, 32, and William Russell Matix, 34.

Two of a Kind

According to FBI documents, Matix and Platt first met in the early 1970s while serving in the U.S. Army at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. Both had been part of the Military Police Unit during their time at Fort Campbell, and both were honorably discharged from the Army by the end of the ’70s.

Matix moved to Miami in 1984 on the invitation of Platt, who was working in a landscaping business with his brother, Tim. On Dec. 30 of the prior year, Matix’s wife, Patty, had been brutally murdered, along with another employee, while working in a cancer research lab at Riverside Hospital in Columbus, Ohio. The victims, bound and gagged in the laboratory, were stabbed numerous times and had their throats slashed. Matix told many of his friends that police were harassing him as a prime suspect in the murders and that’s why he wanted to move out of town; he was never charged. To this day, the murders remain unsolved.

Matix received $350,000 in insurance money from his wife’s death. FBI reports indicate that Matix invested the major portion of the insurance money in a trust fund for his daughter, Melissa. Patty had given birth to their daughter two months before she died.

Platt’s wife, Regina, also met a violent demise, albeit self-inflicted. On Christmas Eve in 1984, she killed herself with a shotgun while in the couple’s bed at their home. It was later suggested that Regina had been depressed, in part, because Platt had forced his wife into sharing herself sexually with Matix. Her death was considered a suicide. Her husband was considered a suspect, but there wasn’t enough evidence to convict.

When Matix moved to Miami, Platt broke off from his brother. Matix and Platt opened their own landscaping and tree removal business, called Yankee Clipper. Investigators believe it served as a front for them to scope out the businesses that they would later rob. Both men lived not far from the South Dixie Highway area, where most of the banks and businesses they were robbing were located.

In the month leading up to April 11, Miami homicide detectives had a nickname for the two yet-to-be-identified suspects. They called them the “rock pit gang”—a fitting tag with a deadly backstory.

The Dark Side

The Dark Side

Grogan and other FBI agents had been on the lookout for the 1982 black, two-door Monte Carlo, which had been used in a bank heist. The car had been taken on March 12, 1986 from a man named Jose Collazzo. The Miami resident drove to a lake near Tamiami Trail, where he enjoyed target-shooting with his Smith and Wesson Combat Masterpiece Model 14, as well as a .22-caliber rifle.

Two men pulled up in a white Ford pickup truck and struck up a conversation with Collazzo; it wasn’t unusual for people to chat each other up while target shooting. But the two strangers had ulterior motives. They drew their guns and demanded that Collazzo give up his wallet, his guns and his car. Even though Collazzo willfully complied, the two men shot him at close range at least three times, then tossed him into a rock pit.

Collazzo was still alive, but he played dead. After the two men drove off, Collazzo, bleeding and in serious condition, somehow struggled to walk 3 miles and get help. He provided a description to police of the two men and the car they had stolen.

A few months later, in May, a fisherman in the Everglades discovered the bones of another man, who had been missing since early October of the previous year. The man had told his family that he was going to a rock pit south of Tamiami Trail to target shoot; his gold Chevrolet Monte Carlo had been used during the robbery spree. The man’s remains were identified as Emilio Briel. Platt and Matix had shot and killed the 25-year-old.

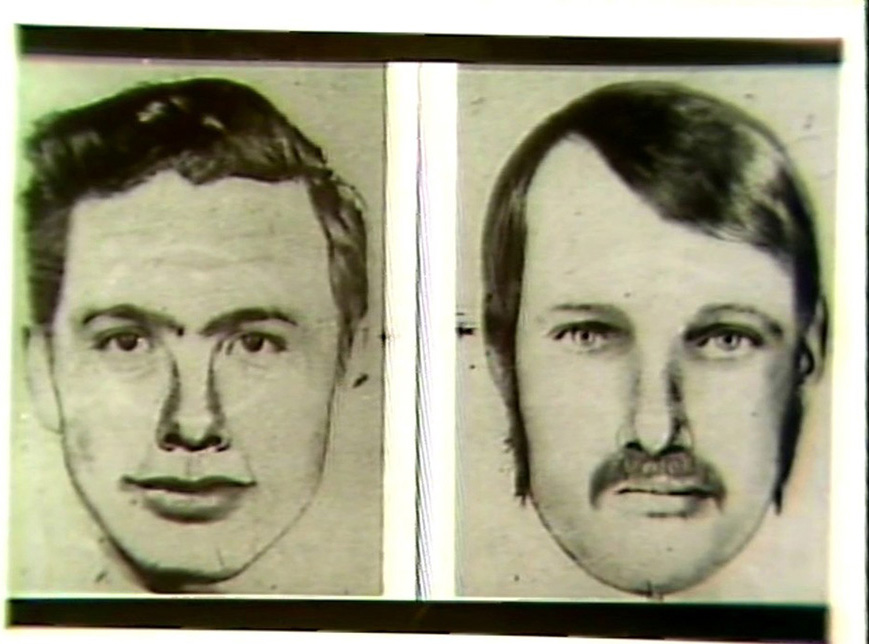

On the morning of the surveillance, the Miami FBI didn’t yet know the names of the suspects—nor did it know Briel had been murdered. But they had composite sketches of the two men based on Jose Collazzo’s interviews.

“April 11, 1986, was just a routine day,” says FBI Special Agent Edmundo Mireles. “I mean, I guess now looking back, it was the quiet before the storm. But, you know, nobody knew then that the storm was coming.”

The Chase Is On

Mireles only had been with the Miami FBI bureau since April 1985, after being transferred from the Washington, D.C., field office; it was his fifth year, overall, with the FBI. His wife, Liz, had been assigned to the Miami bureau; the two had met in Washington, and the transfer allowed them to work in the same city. Mireles was the passenger that day in Unit 55, a Dodge, with Special Agent John “Jake” Hanlon.

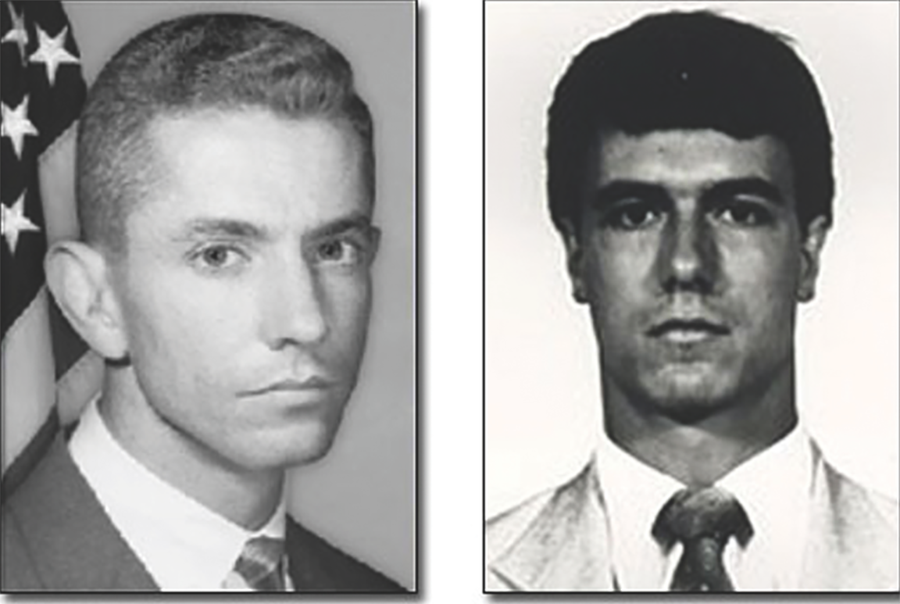

Riding with Benjamin Grogan that day was FBI Special Agent Jerry Dove (Dove is pictured left; Grogan, right). The 30-year-old native of Charleston, West Virginia, had graduated from two colleges in his home state—he received his bachelor’s degree at Marshall University, then earned his law degree at West Virginia University in 1981. A year later, he joined the FBI.

Hanlon and Mireles were assigned to keep watch at the Professional Savings Bank at 130th Street and South Dixie Highway. “We found a good spot in a shopping center where we could see the bank parking lot, and the front and side entrances,” Mireles says. Not long after they had set up surveillance, they heard Grogan’s call: “Attention all units.”

Hanlon threw the Dodge into gear and rolled onto South Dixie. Mireles had been prepared to load his shotgun, strap on his body armor, and put on his raid jacket with FBI printed on the back in big yellow letters. But there was no time for that. Hanlon accelerated, and they were able to catch up with Grogan and Dove, and the black Monte Carlo, at 117th Street.

A third car, driven alone by FBI Special Agent Richard Manauzzi, joined the pursuit. By now, Dove had placed a blue bubble light on top of the dashboard.

“That and the siren caused a reaction,” Mireles says. “I could see the two men in the Monte Carlo turn around to see who was behind them.”

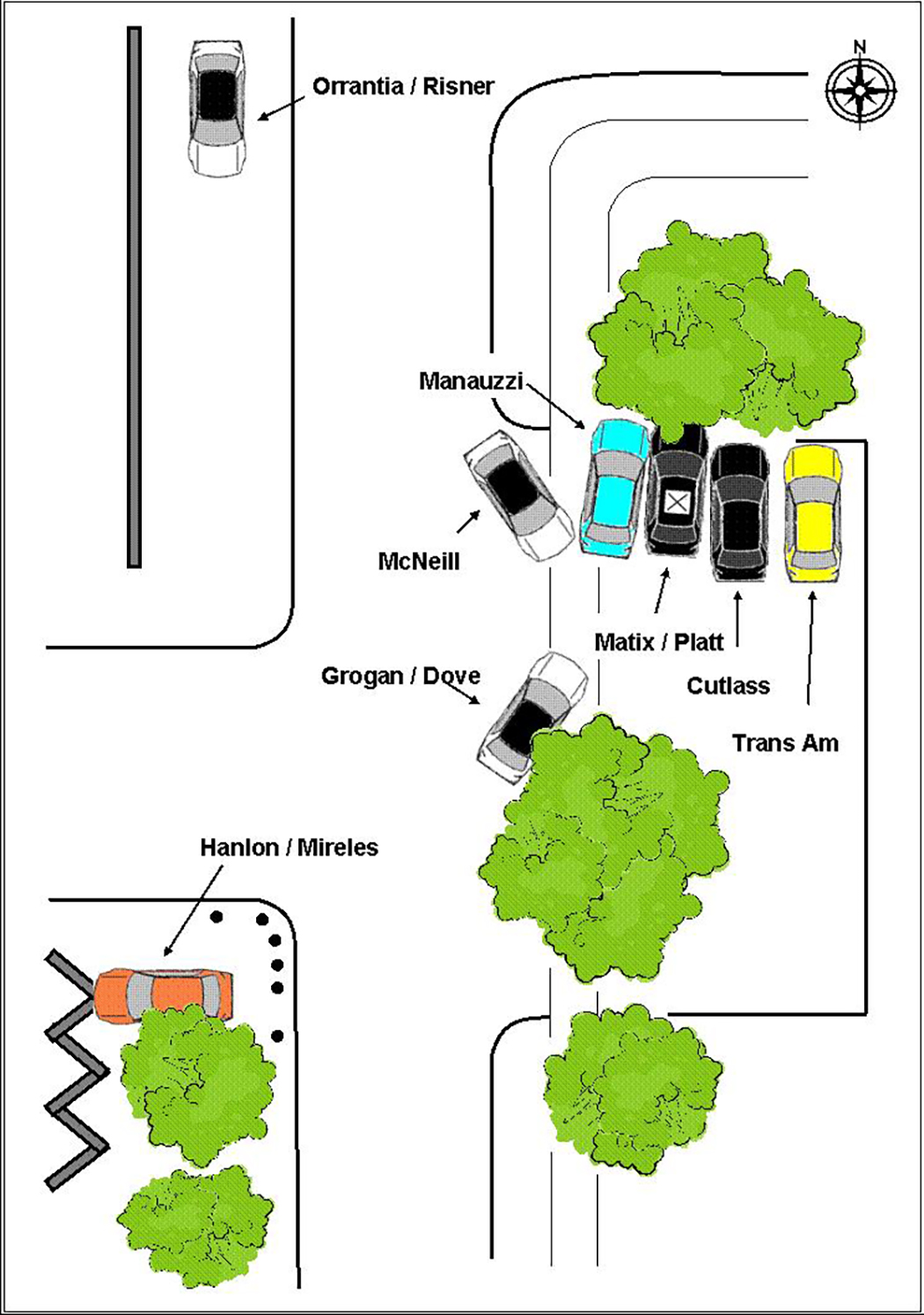

According to Bureau File 62-121966, the Monte Carlo turned onto Southwest 82nd Avenue, near the intersection of Southwest 122nd Street. That’s when Manauzzi attempted to stop the Monte Carlo by slamming into its driver’s side; he then rammed it a second time. The Bureau File reports that “the vehicle chase came to an end with the subjects’ vehicle wedged between a parked car, an FBI vehicle and a tree facing northbound in the parking area of a front yard in front of 12201 SW 82nd Avenue.”

The car that Grogan was driving made a U-turn and parked behind the back of the stolen car. Meanwhile, Hanlon had smashed his car against a wall on the west side of 82nd Avenue.

Task force supervisor McNeill pulled up in a car alone. Two additional special agents, Gilbert Orrantia and Ron Risner, arrived in separate cars and were positioned across the street.

“There was a point when all the cars came to a rest,” Mireles says. “Manauzzi had pinned them in. [McNeill] came in from the north and parked next to Manauzzi’s car. Then, everything [went quiet]. No engines revving, or cars crashing or tires screeching. Everything was just dead silence.”

The silence didn’t last long.

Shots Ring Out

Mireles remembers McNeill taking cover and yelling, “Police, FBI. Put your hands up.” As soon as McNeill spoke, the two suspects began firing their weapons.

“They were shooting at [McNeill], and [Grogan and Dove] parked behind the Monte Carlo,” Mireles says. “I decided to run across the street to reinforce [Grogan and Dove].”

Mireles recalls the scene beginning to play like a slow-motion movie. He could see Platt behind the driver’s side door, which was pinned in, with his weapon up and firing.

“I could distinguish his gunshots because he had a semi-automatic, so his gunshots sounded more like pops, and I could see the casing as it was ejected,” he says.

“Then I heard, ‘Kaboom! Kaboom! It sounded like a cannon. I thought to myself, ‘Someone’s got a shotgun, and they’re using it against us.’ It was an intimidating sound.”

At 9:35 a.m., the dispatch operator alerted all units of shots being fired at the scene. She tried to radio Grogan’s car.

“2960? 2960?” the dispatcher asked. But Grogan wasn’t answering. Another car did.

“Officers down!”

The dispatcher echoed the report over the airwaves: “Officers down! Officers down!”

Raging Fire

“With most gunfights, most police shootings, they happen in five to 10 seconds,” Mireles says. “It’s a car stop. ‘Hey, sir, can I see your license.’ And then someone runs, or someone’s down, that’s how fast it happens.

“But this went for five minutes.”

It was later discovered, from witness interviews, that unsuspecting residents continued driving around the neighborhood as the shootout was happening because they thought a scene from Miami Vice, a top-rated TV show from that era, was being filmed. But there was nothing staged about the events of April 11.

Platt, the passenger, fired across the front of Matix through the driver’s side window. Matix was trying to get out of the car, but he was shot by Grogan in his forearm. McNeill then shot Matix in the head and neck. Platt managed to get himself out of the car, and Dove shot him in the chest. Dove hit him twice more, in the thigh and foot, and another agent shot Platt in the back.

Manauzzi was the first agent wounded, taking fire from Matix’s shotgun. As McNeill took cover behind Manauzzi’s car, he was shot in the hand by Platt. McNeill tried to reload his revolver with his other hand, but Platt shot him in the neck with a high-powered Ruger Mini-14 semi-automatic rifle. Orrantia, pinned down with Risner across the street, was wounded in the hail of bullets.

Though Grogan and Dove had wounded the suspects [Platt also had been hit by shots from both Orrantia and Risner], they were trapped and kneeling on the driver’s side of their car. Grogan, the best shot in the field that day, also had lost his glasses when they flew off his face after his car stopped abruptly; they were later found under the brake pedal of the car.

Platt maneuvered around the back of Grogan and Dove’s car. At close range, he killed Grogan with a shot to the chest; he then shot Dove twice in the head, killing him instantly.

Hanlon had run across 82nd Street and into the fray to back up Grogan and Dove, a decision that almost cost him his life. Platt shot him, first in the fingers. When Hanlon saw that Platt had his gun down, he lifted his leg to kick him. “That was when he shot me in the groin,” says Hanlon, who worked as a Broward assistant state attorney among other jobs after he left the FBI. “I could see Platt was dying; he was all shot up by then.”

Hanlon had run across 82nd Street and into the fray to back up Grogan and Dove, a decision that almost cost him his life. Platt shot him, first in the fingers. When Hanlon saw that Platt had his gun down, he lifted his leg to kick him. “That was when he shot me in the groin,” says Hanlon, who worked as a Broward assistant state attorney among other jobs after he left the FBI. “I could see Platt was dying; he was all shot up by then.”

Mireles also had been shot by Platt. His left arm was shattered. He recalls going in and out of consciousness, but he remembers clearly the moment he decided he wasn’t giving up. “I’m thinking, ‘Well, if I’m going to die, I want to make sure they’re dead, too.’ ”

The End

Somehow, Matix had managed to get into Grogan and Dove’s FBI car behind the Monte Carlo. Mireles was able to crawl to the rear of McNeill’s car; he could see Platt’s feet as the killer attempted to move to the front of Grogan’s car. Mireles somehow dragged a shotgun into position: “Twelve .32-caliber pellets fired out of the shotgun barrel, and four hit Platt’s feet,” he says. “He stumbled but kept on moving.”

Mireles peeked around the car and saw that both Platt and Matix were in Grogan and Dove’s vehicle. A witness recalled later that a man, identified as Platt, got out of the car and walked within 8 to 10 feet of a man in a red shirt. That was Mireles. Platt fired four or five times at him before stumbling back to the car and getting in. None of the shots connected.

Mireles made it to his feet and, as he describes, like a walking dead man, took out his revolver, a Smith and Wesson 686, and staggered toward the car. “Stop, set, aim, fire. Every time I fired, I got closer and closer,” Mireles says. Three of his first five shots struck Matix in the face, including one that went into his neck and severed his spinal cord.

Mireles reached the driver’s side door. “I had one bullet left … I [didn’t] need to save it. That’s when I shot Platt in the chest. It was that round for sure [that finally killed Platt].”

In all, more than 140 rounds were fired. With the exception of minor wounds to Manauzzi by shotgun pellets, all serious wounds inflicted were from Platt’s Ruger Mini-14 .223 caliber rifle, including the shots that killed Grogan and Dove. Platt fired a minimum of 40 rounds. Matix fired once and possibly twice from a shotgun, and each of the subjects fired three rounds from .357 magnum revolvers they were carrying.

Nine of the 10 men involved were shot. Matix was shot six times and Platt 12 times. McNeill, Hanlon and Mireles were seriously injured. Manauzzi and Orrantia also were injured. Risner was the only one to escape unscathed.

Mireles was later awarded the FBI’s first-ever Medal of Valor for delivering the shots that killed Platt and Matix. After he retired in 2004, Mireles wrote a book with his wife, Liz, titled FBI Miami Firefight: Five Minutes that Changed the Bureau. The book’s title acknowledges how the incident forced the FBI to reevaluate training, tactics and equipment. Indeed, law enforcement all over the country would update their service handguns to semiautomatic weapons (instead of ones that require reloading) because of Platt and Matix’s ability, though outmanned, to keep eight FBI officers pinned down.

Through the years, FBI directors have come to South Florida to acknowledge the anniversary of the shootout, and the service and sacrifice of Grogan and Dove. A decade ago, then-FBI director Robert Mueller addressed a crowd at the 25th anniversary of the shootout. And six years ago, then-FBI director James Comey attended the naming and dedication of the Benjamin P. Grogan and Jerry L. Dove Federal Building, the new home of the FBI’s Miami bureau, located in Miramar. Mireles’ shotgun, Jerry Dove’s pistol with the bullet hole through the slide, the robbers’ weapons, and the FBI credentials of Grogan and Dove are all part of a display inside the building.

“That was a day that changed not just the FBI, but all of American law enforcement,” said Comey on April 10, 2015 at the building dedication.

“We have worked for three decades to make good come from that, so that lives were saved, people were protected, and the bad guys were brought to justice in a way that was not possible before that day in Miami.”