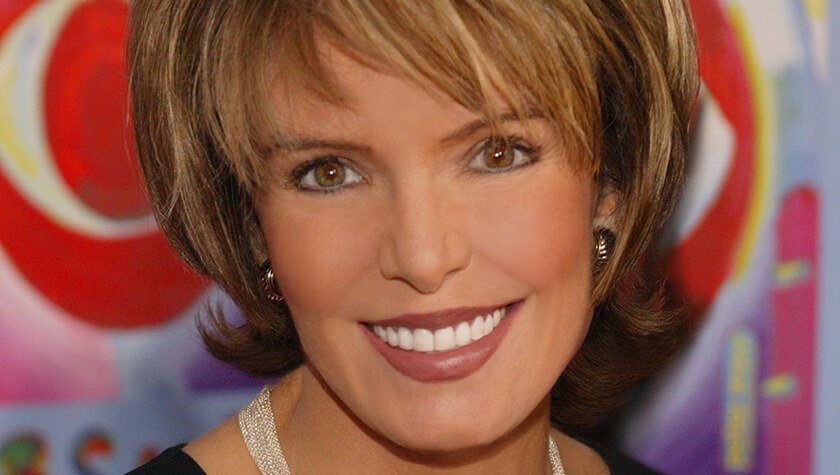

Lesley Visser had her armband. It was Jan. 1, 1980, the dawn of a new decade and, so it seemed, a new era. After being denied postgame access to locker rooms for player interviews early in her career as a sports writer for The Boston Globe, the armband meant that Visser—already the first woman to cover an NFL team as a beat writer (the New England Patriots in 1976)—could join male reporters inside the locker room of the victorious Houston Cougars, who had defeated Nebraska at the Cotton Bowl Classic.

Lesley Visser had her armband. It was Jan. 1, 1980, the dawn of a new decade and, so it seemed, a new era. After being denied postgame access to locker rooms for player interviews early in her career as a sports writer for The Boston Globe, the armband meant that Visser—already the first woman to cover an NFL team as a beat writer (the New England Patriots in 1976)—could join male reporters inside the locker room of the victorious Houston Cougars, who had defeated Nebraska at the Cotton Bowl Classic.

But Houston coach Bill Yeoman had other ideas.

“[Yeoman] yells out for everyone to hear, ‘I don’t give a damn about the Equal Rights Amendment; I’m not having her in my locker room!’ I was mortified,” Visser says. “He took my shoulders and marched me out. I didn’t want to lose it in front of the [other reporters and cameramen], so I walked to the top row of the Cotton Bowl, and I cried.”

As chronicled in her new book, Sometimes You Have to Cross When It Says Don’t Walk, being a pioneer in print and on television comes with its share of challenges. But it’s also provided the longtime CBS sports reporter with the kind of life she only could dream about when she dressed up as Boston Celtics great Sam Jones for Halloween as a child.

“I still dress up as Sam every Halloween,” Visser notes. “He calls me. ‘Lesley, you’re 64. Give it a rest.’ ”

On television, she was the first woman to cover the World Series. The first woman to report from the sidelines on “Monday Night Football” and during a Super Bowl broadcast. And, in 2006, Visser became the first and only woman enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame (via the Pete Rozelle Radio-Television Award).

The South Florida resident, also a member of the National Sportscasters and Sportswriters Association’s Hall of Fame, spoke to Lifestyle about her trailblazing career.

What sparked your original interest in sports?

I did a story a few years ago about these fraternal twins, Darion and Darius Atkins. Both are like 6-foot-7. One played basketball for Virginia; the other [studied] at the Joffrey Ballet School [in New York]. Their mother said to me, “That was their passion pool.” Same for me. If sports wasn’t in my gene pool, it was in my passion pool.

What makes sports so great is that it’s unscripted. Maybe you and I could get hired by a TV show, but they would be in control of where it goes or how it ends. In sports, you don’t know. And, from time to time, you get surprised.

When did the idea of becoming a sports writer become tangible?

It never seemed probable. But it didn’t mean I didn’t want it. I would say, around age 10, I started to read Sports Illustrated and Sport magazine. The writing appealed to me, and I already liked sports.

Athletics weren’t going to be open to me; I didn’t think I was going to become Billie Jean King. … I remember playing in the media tennis tournament at Longwood [Cricket Club] in Boston with Bud Collins [the late sports writer for The Boston Globe and legendary tennis announcer], and we won. And the way we won was that Bud told me, “Go to the net, and don’t touch the ball.”

But I could always talk the language of sports. I found it easy. In the neighborhood, I had an opinion on the Red Sox. We played pickup football games in the streets. I was a total tomboy.

My dad wasn’t from the United States [he was born in Amsterdam under Nazi occupation]. The three things I loved—football, basketball, baseball—he had no clue. But when I told my mom I wanted to be a sports writer, she said, “That’s great. Sometimes, you have to cross when it says don’t walk.”

Could it be that sports provided an escape given how often your family moved (11 times, Visser writes in her book) and how your parents eventually divorced?

I wouldn’t say escape. I would use the word embrace. I could move to any community and embrace that team. Pro team, college team, high school team. The Baltimore Orioles weren’t going to replace the Red Sox [as my favorite team], but I could embrace the Orioles and then talk about the team to people. I try to tell my single female friends: This is the language men speak. And it’s a nonthreatening language.

You’ve inspired many other women to enter sports reporting, but you didn’t have that trailblazer to follow in the 1970s. What kept you driven?

At that age, and try to think of yourself in your 20s, you’re protected by your innocence. Back then, I thought I would have made it anywhere. Maybe that helped me at the Globe. You weren’t going to study more than I was. You weren’t going to report with more intensity. I was going to make the Globe proud. And I was going to make the name Visser proud.

Was it important to go above and beyond so that your gender never came into question?

There are simultaneous truths here. One, yes, I was really prepared. No one was going to say that I didn’t understand the Washington Redskins’ counter trey play. But, two, I never accepted the notion that women should get something different or better.

I do feel that I’ve had a billion-dollar career. I’ve been behind the Iron Curtain. I was at the fall of the Berlin Wall. My first salary at the Globe was $10,000? $12,000? But I was also going to the Final Four. I never took that for granted. I always had an attitude of gratitude.

Has the Me Too movement cast new light on experiences that maybe you view differently now?

I had the blessing of four men who I owe my career to: Vince Doria, [former sports editor at] the Globe; Ted Shaker, [former executive producer for] CBS Sports; Sean McManus, now my boss [and chairman of CBS Sports]; and Les Moonves, the CEO of CBS. None of those men sexually harassed me. Or economically harassed me. Nor did I fail to get an assignment because I was a woman.

Now, many, many players hit on me along the way. And what the movement has done, after reflecting on it, is make me think that maybe I shouldn’t have laughed it off [every time]. I’d say to a player, “Now, your mother didn’t teach you to talk like that.” That immediately changes the dynamic; no player wants to embarrass his mother. But I never went to the head coach or my boss or my lawyer to complain. I used humor to deflect.

As one of the first women through the door, did you feel it was important to handle awkward situations without drawing attention to yourself?

You can represent a lot by the way you carry yourself. I wasn’t there for any other reason than to see what happens on the next play. I wasn’t flirting with players. I was covering the team. I was trying to be a pro.

Here’s the difference. If [Carolina Panthers quarterback] Cam Newton had [disrespected a female reporter as he did at a news conference during the 2017 NFL season] back when I started? Everybody would have sided with Cam. The reporter asked a legitimate question; the fact that [Newton] had to apologize … that made me emotional.

It’s only 40-some years, but we’ve come a long way.