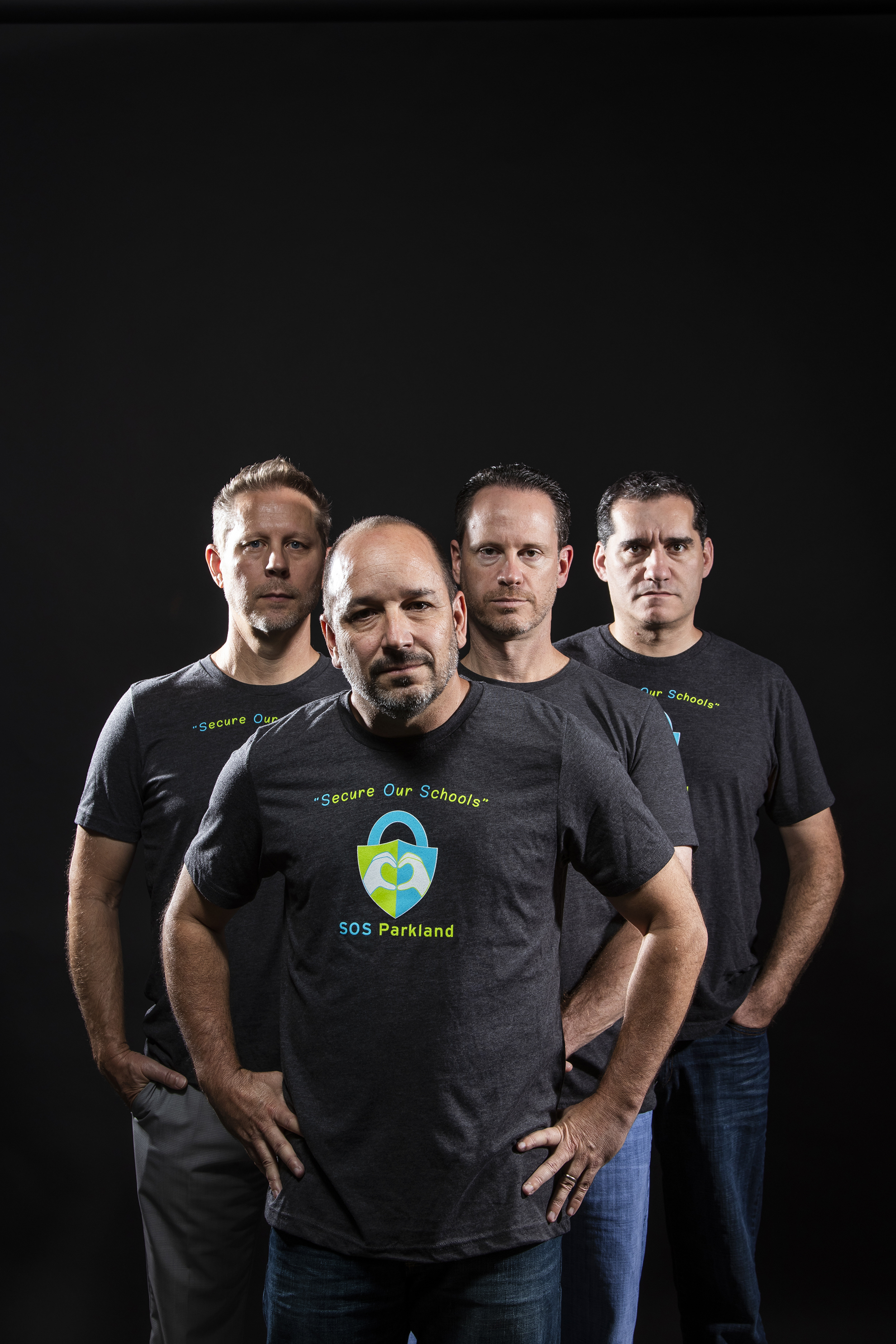

Photo by Eduardo Schneider

Noel Glacer walked into a seminar earlier this year being hosted by a fledgling nonprofit in Parkland. His son, Jake, then a junior at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, had witnessed four classmates being shot (one of whom died). Like so many other parents in the aftermath of the Feb. 14 massacre that claimed 17 lives, Glacer wanted to effect change in his community.

The question was how.

“Everybody used to say, ‘You live in the Parkland bubble.’ Well, that bubble had burst,” says Glacer, founder of the security division at Recruit Group, an executive search and staffing agency. “I was looking for an outlet, but I didn’t know where to go.”

Glacer and two other fathers—Cary Fronstin and Dave Lotz—with children at Parkland-based schools not only found their outlet, but they helped to form the board of SOS (Secure Our Schools) Parkland, a nonpartisan organization created by Bo Landy with a clear albeit complicated mission. In addition to advocating for school security awareness, SOS Parkland is ready and willing to help fund physical safety measures at five Parkland public schools—Park Trails Elementary, Heron Heights Elementary, Riverglades Elementary, Westglades Middle and MSD.

“We didn’t want to be the group that said, ‘Somebody should do something,’ ” says Landy, owner of Landy Marketing, whose two children attend Park Trails and Westglades. “We want to be the somebody that does do something.”

Landy’s relentless persistence, along with some of Glacer’s connections in the safety industry, have resulted in donations of equipment (more than 200 digital cameras) and offers to donate additional products (card-access systems, intercom systems, metal detectors), as well as the labor to install them.

But as Landy and his board have discovered, the politics of school safety don’t lend themselves to a quick fix. Implementing security measures at individual schools, no matter the scope, requires navigating “an unbreakable wire mesh,” as Glacer calls it, that turns any sprint into a marathon.

Efforts to promote ballistic shielding, for example, necessitated involvement by the School Board of Broward County, further evaluation at the district level, acceptance from the principal at the Parkland school, and approval from the School Advisory Council. At press time, ballistic shielding had been installed at Heron Heights thanks to a manufacturer’s donation, and SOS Parkland had donated toward the intial phase of shielding installed at Westglades.

“Why aren’t the schools doing what, to the outside observer, should be done?” says Lotz, chief operations officer at Quality Surgical Management, whose children attend Westglades and Heron Heights. “The quick answer is that we can only do what we have been [approved] to do.”

Landy hopes that the group’s early efforts will bear more fruit after the nonprofit campus-safety group Safe Havens International presents the second portion of its district-wide analysis to the school board. In August, Safe Havens released an initial report that made such recommendations as adding smart cameras, panic alarms and more emergency preparedness training, while arguing against metal detectors. The second and more-detailed phase, a vulnerability assessment of each school’s day-to-day operations, was expected by the end of October.

“Has it been frustrating? Yes and no,” says Fronstin, executive vice president of building management for Foundry Commercial, who has a daughter at Westglades. “It’s still [less than a year] since the events of Feb. 14. And dealing with the district and the school board was always going to be a long and involved process. But we’ve already seen ballistic protection installed. … And once one initiative is complete, we’ll move on to the next. The end will justify the means.”

“Three things have to come together for a security measure to go into place [when it’s not a districtwide initiative],” Landy says. “It has to be advised by a security expert; the district and school board [and principal] have to be OK with it; and you have to have the money [from private donations] to pay for it. When the vulnerability report comes out, and we find out the things that the schools can use, we’ll need to have [private donations] to help fund these initiatives.”

To that end, SOS Parkland is in the process of planning more fundraisers for 2019, in addition to its ongoing efforts to work with manufacturers and integrators in the safety industry. Landy says the passion project has turned into another full-time job, but he’s not complaining.

“If you would have told me on Feb. 13, we’re going to need you to set aside 30 to 40 hours a week for another project—and do it for free—I probably would have laughed,” Landy says. “But we’re talking about the lives and safety of 8,000 kids in Parkland. You have to make it more secure. If not us, who? There’s no one lined up behind us to take on this battle. …

“And who knows? Maybe we inspire someone in another state to start an organization that protects their schools—and maybe that organization saves one child’s life. Then, it’s all worth it.”

Visit sosparkland.org for info about the organization.