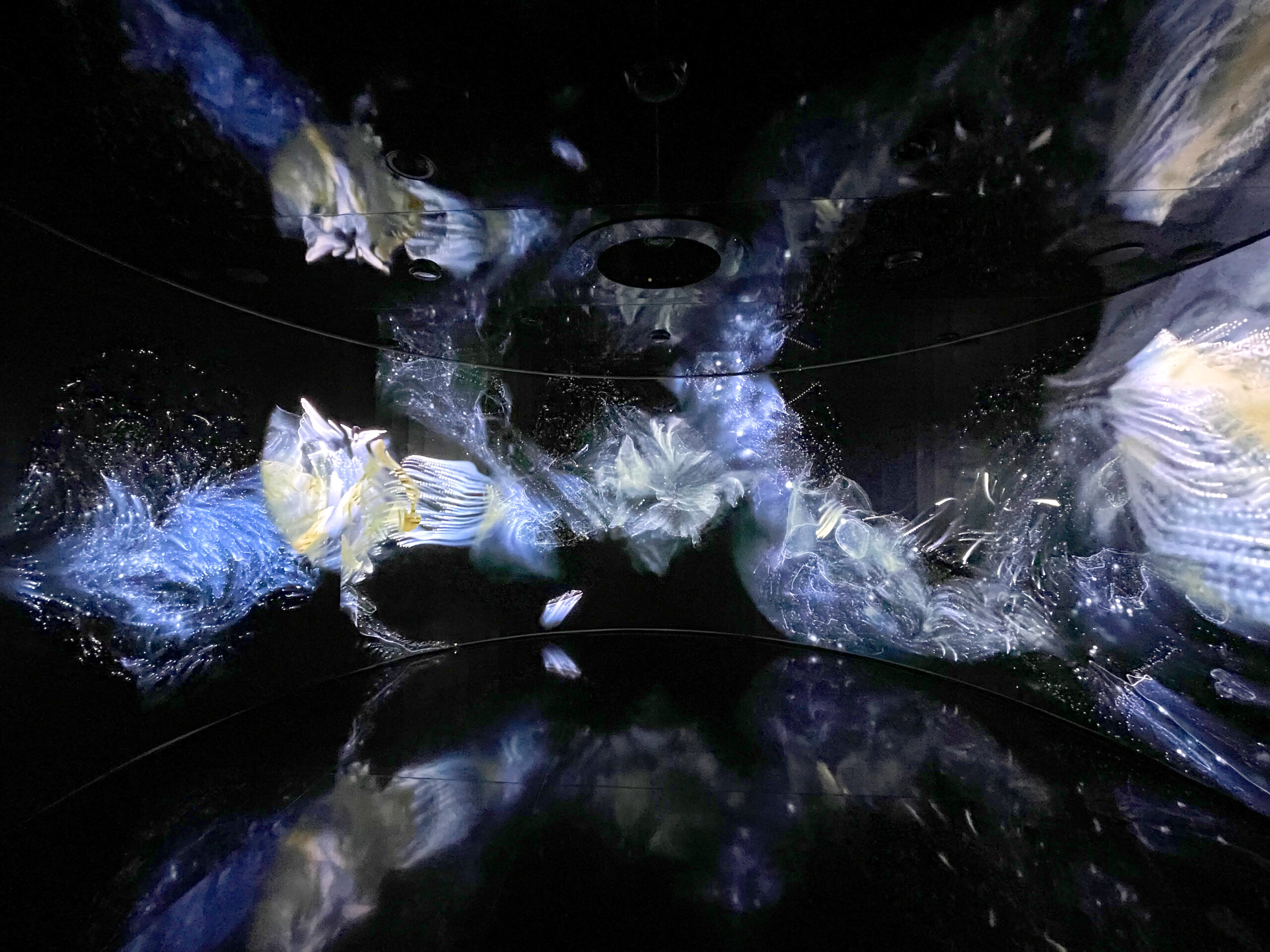

Pictured above: Connor Serrano with his mom, Jessica

On a humid summer evening, Julie, a single mom clad in a blue dress, black blazer and sensible pumps, enters a meeting room at the Boca Raton Community Center.

It’s where a transgender support group is about to begin.

A mix of transmen, transwomen and nonbinary attendees mingle and grab snacks from a folding table before choosing from chairs arranged in a large circle. The air-conditioner hums in the background, but as Julie nervously runs a hand through her blonde bob, a droplet of sweat runs down her back. She scours the room for a seat.

She cannot believe she is there.

Other than seeing Caitlyn Jenner on TV, she didn’t know anything about being transgender. She had never met a transgender person—at least none that she was aware of.

And yet here she is sitting in a group and desperate for insight. Her chest tightens just acknowledging the bewildering incongruity of her situation. She wants to run but instead inhales deeply, slides into an empty chair and nods politely at those around her. When attendees start sharing stories of trials and triumphs, she leans in, focusing on every word as though they hold the meaning of life.

Because for Julie—whose 14-year-old-daughter Samantha just told her she was really a boy—they do. And she has so many questions.

Toward the latter part of the meeting, she finally musters the courage to speak. But before she begins, Julie breaks down and starts crying uncontrollably.

“My beautiful girl says she’s male!” she manages to blurt through tears. “I don’t know what to do. Please help me!”

They’re Coming Out

Transgender (aka “trans”) awareness is at an all-time high, with contemporary trailblazers such as Jenner, Laverne Cox, Chaz Bono and Jazz Jennings paving the way for younger generations. Richly complex characters are featured on popular TV shows like Pose, Supergirl and Euphoria, while Variety magazine dedicated an entire volume to being “trans in Hollywood.” National Geographic published a special issue about trans kids and their families, and for the first time in U.S. history, four trans candidates were voted into public office, most visibly Danica Roem, who was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates in 2017.

And the population is growing. According to the Williams Institute, a UCLA Law School think tank, there are an estimated 1.4 million transgender individuals living in the United States—double from 2011. Florida is home to the sixth-largest population, with 100,000 trans residents, the biggest percentage being ages 18 to 24. These figures are expected to rise as awareness increases.

Still, in a binary society where biology traditionally dictates who’s male or female, discovering a child is trans can send even the most confident, competent parent into a tailspin. They experience confusion, disbelief and helplessness. They mourn dreams of grandchildren and white weddings and may feel shame, isolation and marginalization. They worry their kids will be bullied at school or shunned by their extended families and religious communities. Some experience guilt for not realizing sooner that their child was trans. Others may have their own internalized transphobia to confront. Mostly, parents fear for their kids’ safety and what the future holds.

“My immediate reaction was to be extremely upset for my child,” says Mary of Boynton Beach, whose 19-year-old trans daughter, Amy, came out via email at 14. “The fact that she had to write a letter to express all the emotional pain she’d felt since she was 11 broke my heart.” Mary was accepting but also panic-stricken. “I didn’t know how I was going to help her,” she recalls. “It’s one thing to say you want to be a girl. It’s another thing to present like a girl, try to look like a girl and become that girl. I didn’t know where to find resources. I was just sitting at a computer staring at the screen trying to find people.”

Helene of Deerfield Beach has two trans daughters. She recalls the moment in 2004 when her first biological son came out at 17. “We were on the couch and Jackie was resting her head in my lap. She’d been acting odd for a while so I asked what was wrong,” Helene says. “She didn’t answer so I assured her I’d love her no matter what. Then to lighten the mood I tried to think of the most outrageous possibility and joked, ‘Even if you’re a transsexual murderer.’ She looked up at me with big green eyes and said, ‘Well, I’m not a murderer.’ ”

“I just went full deer-in-headlights,” she admits. “I was very judgmental back then, but I had to learn to accept that I didn’t own my child, and that she didn’t owe me anything. My job as a parent was to make her a happy, productive human being, not impose on her who I wanted her to be.”

When her younger daughter, Roberta, came out last year, she was a lot more accepting. “Roberta was such an uptight human as a man, with her shoulders wrapped around her ears all the time,” says Helene, who started the Facebook support page, Parents of Transgender Children, which has more than 8,000 members. “She’s so much more affectionate and expressive in her emotional range now. It’s like it freed her.”

The Search for Answers

Even Jeanette Jennings, well-known mother to I Am Jazz star and trans activist Jazz Jennings, initially feared for her child’s well-being. “When Jazz first said she was a girl, I thought it was cute. But when she became ‘insistent, consistent and persistent,’ I looked it up and she hit all the markers,” recalls Jennings, a South Florida resident and original member of Helene’s Facebook page. “I diagnosed her before ever taking her to see a professional and then had it confirmed. It was very difficult to digest. My husband and I were devastated at the time. We worried about her future and if she’d be ostracized.”

Resources were scant back then. Jeanette remembers going to the library seeking books about raising transgender preschoolers. “There was nothing,” she says. “I could not get my hands on a single resource other than for older kids and about suicide rates. It was horrifying, and there were no parents to talk to who had children as young as mine.”

What helped most, she says, was finding a qualified gender therapist. It wasn’t easy. “We had no idea where to go. We eventually found someone who evaluated Jazz and confirmed she was transgender female. She said she’d never seen someone display such outward signs,” Jeanette recalls. “But she explained that she couldn’t work with us because she specialized in adults. Jazz was 3 years old.”

Eventually, she found clinical sexologist Marilyn Volker, whom she called “instrumental” in who Jazz is today. “She gave us the initial courage to allow Jazz to transition socially [starting when she was 5 years old],” Jeanette says. “She made us feel like we were doing the right thing and what was in Jazz’s best interest. Without her I don’t know where we’d be.”

Volker is a trailblazing gender therapist who began teaching about gender issues back in the 1970s, when she coordinated the Sexuality Division of the Institute of Sexism and Sexuality at Florida International University. “I believe there are no accidents in life,” says Volker, 73, who also has degrees in working with special-needs populations. “As a minister’s kid and former minister’s wife, I was taught we value all people—not just white, cisgender, heterosexual, married people with children.

“Because of my special-needs degrees and experience working with many children and teens who felt different or marginalized, I was drawn to those who learned and expressed themselves in different ways. Safety for all children has always been my passion.”

Fact & Fiction

Brandy, 12, is a wispy trans girl with expressive hazel eyes and a big smile. As early as age 2, she wore her sisters’ princess dresses over clothes. As she grew older, she asked for a Cinderella bike, then only girls’ clothing. Later, she requested she be addressed by female pronouns.

Still, it took her mother awhile to realize her little boy identified as a girl. The epiphany came while watching a Dateline documentary about a trans child.

“I just cried and thought, ‘So this is what’s going on.’ I cried because I felt I let her down,” says Brandy’s mom, Jenny Burak of West Palm Beach. “I never put two and two together. Honestly, back then I thought she was gay.”

People often confuse gender identity with sexual orientation.

“That’s frequently an initial thought because coming out as gay or lesbian seems more acceptable,” says Jamie Weiss, therapist and transgender image consultant in Deerfield Beach. “I explain to parents that a child can be transgender—but also may or may not be gay. Sexual orientation is to whom one is sexually, romantically or emotionally attracted. Gender identity is one’s psychological self, or how one internally identifies. It’s apples and oranges.”

Another common misconception is that a transgender child can be “fixed.” According to the Human Rights Campaign, trying to change a child’s gender identity is dangerous and can cause permanent mental health issues. This includes “reparative” or “conversion” therapies, which are typically faith-based and condemned as “psychologically harmful” by the American Psychological Association, American Medical Association and other, similar organizations.

“When parents bring a child to therapy, they’re at the end of their rope after trying to resolve things themselves,” explains David Wohlsifer, a Boca Raton therapist and clinical instructor at Florida Atlantic University’s Sandler School of Social Work. “They’re vulnerable and need to be met where they are and not judged. I teach them their child isn’t broken and help them create a new narrative.”

Parents often take “blame” for their child’s trans identity—as if playing more sports or playing with more Barbies would have made a difference. It wouldn’t have. Rather, gender experts cite a combination of nature, nurture and culture.

“I reassure them that gender is not a result of parenting,” says Miami therapist Carol Clark, director of the International Institute of Clinical Sexology and president of the International Transgender Certification Association. “I explain that the word ‘transgender’ includes a huge variety of gender identities and expressions, and that no one event causes any of them. I tell them they don’t have that power.”

How to Know

While there is no official test, there are diagnostic criteria to tell if your child is trans. According to the American Psychological Association, trans children “consistently, persistently and insistently express a cross-gender identity and feel their gender is different from their assigned sex.” The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, states that for a child to be diagnosed with gender dysphoria, they must have “a marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and assigned gender” for at least six months; experience “clinically significant distress or impairment in social, school or other important areas of functioning” and must experience at least six of eight designated symptoms.

However, “You can’t know with 100 percent certainty whether or not someone else is transgender unless they tell you themselves,” says Miami therapist Maylin Batista, dean of students for the International Institute of Clinical Sexology.

Further, it’s important to note that gender therapists don’t have agendas. “We have parents concerned that because we’re pro-trans we want their kids to come out as LGBTQ,” says Michael Alexander-Luz, lead youth therapist at SunServe, an LGBTQ community center in Wilton Manors. “We remind them that we get no benefit from a kid confirming or coming out as LGBTQ. If a kid’s journey leads them to be cisgender [someone whose identity corresponds with their birth sex], heterosexual, nonbinary [someone whose gender identity is not strictly male or female], etc., then that is where the journey goes. We just help guide them.”

Similarly, while parents may be anxious to know where their child’s journey winds up, it’s imperative they follow their child’s lead. Patience is vital. According to the World Professional Association for Transgender Health’s Standards of Care, children as young as 2 may exhibit features of gender dysphoria—but this may not continue into adulthood. In contrast, continuation of gender dysphoria in adolescents into adulthood is much higher.

The Standards of Care also states that not all trans adolescents display gender-nonconforming behaviors as young children. It’s one reason that when a teen comes out to parents, they assume it’s “just a phase” or attribute it to “rapid-onset gender dysphoria,” the latter being a controversial theory.

“Clients find this extremely frustrating,” says Nikki Saltzburg, a therapist and assistant director of counseling and psychological services at FAU, who often works with trans teens and young adults. “When parents say things like, ‘We know you better than you know yourself’ and ‘How do you know this is who you are and how you feel?’ kids experience that as intense rejection at a time during a developmental phase like late adolescence when they’re transitioning into a different family role. This is no longer their little child. This is their young adult child.”

Lucas O’Ryan is an advocate and the transgender youth services coordinator at Compass Community Center, an LGBTQ center in Lake Worth. “I meet a lot of parents who come in scared their child will be unsafe, unhappy or unsuccessful in their lives, but that’s not usually the case. We are happier and will be more likely to be successful because we can live authentically, and that alone makes us better human beings,” he points out. “Can we get great jobs? Yes. Can we have amazing, flourishing relationships? Yes. I’ve met many transgender young people and adults, and they are creative, sensitive, intelligent, successful people. We have empathy and balance because we’ve lived as both genders. We have integrity and a passion to help others. We’re doctors, therapists, architects, law enforcement officers and firefighters.”

Being Proactive

Still, it’s not easy being different. Add stigma, self-consciousness and the gender dysphoria associated with puberty to the mix, and for trans kids, it’s a recipe for depression, anxiety or worse. When parents reject their transgender child, the results can be devastating. Kids are at risk for dropping out of school, homelessness, substance abuse, depression, self-harm and other mental health problems. Some become sex workers, end up with sexually transmitted diseases or in jail. Others get kidnapped and forced into sex trafficking. Or dead.

The suicide rates are alarmingly high. A 2018 study of 617 adolescents conducted by the American Academy of Pediatrics found that transgender boys reported the highest rate of suicide attempts at a startling 50.8 percent. This is followed by nonbinary adolescents at 41.8 percent, transgender girls at 29.9 percent and kids questioning their gender at 27.9 percent. These numbers are in stark contrast to just 17.6 percent among cisgender girls and 9.8 percent among cisgender boys.

“It’s your prerogative not to accept your child,” says Jessica Serrano of Coral Springs, whose son Connor, 17, came out as trans male a year ago. “But if you don’t, then point them in the direction of someone who will. If you’re not going to do your job, let someone who cares do it for you,” she says, giving her child a bear hug.

“My mother would rather have a healthy child than a dead one,” Connor adds, smiling.

Parents are urged to advocate for their child at school, often a difficult environment for trans kids. A national survey by GLESN, a nonprofit organization that examines the experiences of LGBTQ students, found that 75 percent of trans youth feel unsafe at school. Those who are able to persevere have significantly lower GPAs, are more likely to miss school out of concern for their safety and are less likely to plan on continuing their education.

Call the principal, or a guidance counselor—or both—and request a meeting in order to inform them of your child’s gender-affirming name and pronouns, and to discuss whether your child chooses to be out or in stealth mode, to ensure there is a safety plan in place for your child, and locker room and bathroom use.

“A lot of kids express anxiety about using the bathroom at their school,” says Alexander-Luz. “Some don’t use it at all, which can cause health issues. Some students have to use the bathroom in the school clinic or main office, which singles kids out. One kid explained that the bathroom he’s allowed to use is way across campus, so he ends up 15 minutes late to class and the teacher gives him a hard time for taking so long.”

If a child’s school environment proves toxic, have a backup plan, urges O’Ryan. “Most of our kids deal with bullying and a lot of them attend online school or are home-schooled. It’s incredibly important to have a second option if the school is not a healthy environment for the kids. A lot of kids don’t have that so they drop out or get in a lot of trouble because they can’t go to school to learn and feel safe.”

Support System

There are other ways a parent can provide a supportive, nurturing setting for their trans child.

Help them navigate the coming-out process, especially to siblings (who also will need understanding and attention) and extended family members and friends, and if someone is not accepting of their child, be prepared to cut them off.

Allow them freedom of gender expression, which includes reversible steps such as wearing gender-affirming clothing, accessories and hairstyles.

When age-appropriate, explore a medical transition which may include puberty blockers, cross-sex hormone therapy and gender-affirming surgeries (puberty for a trans kid can be devastating, and with it comes greater risk for self-harm).

Honor their gender-affirming name (as opposed to their birth name, also frequently called their “dead name”) and preferred pronouns (he/him for trans boys; she/her for trans girls; they/them or ze/xe for gender-nonconforming kids).

That last point is paramount, explains Boca Raton therapist Jeffrey M. Landsman. “It’s crucial in terms of the child feeling accepted. It also sets the tone and leads by example to siblings, as well as extended family and friends.”

It also can prevent suicide, points out Alexander-Luz. “It really can save a life. But it’s not about change overnight. It’s about your child seeing you’re trying.”

It’s also vital that parents find their own emotional support, be it through friends, support groups, other parents, gender therapists or online resources. “If you’re not all right, you can’t help your child get through this,” says Julie, who attended that summer support group a year ago.

Julie’s trans son Sam (formerly Samantha) wears his once-long hair cropped and neat. Since he began testosterone, he’s grown facial hair and wears a binder under his shirts to flatten his breasts. His plans include “top surgery”—a procedure in which breasts are removed and a male chest is formed. Julie supports Sam’s transition but still worries. She fears for the challenges he’ll face moving forward, if he’ll be able to have romantic relationships, if he’ll be safe.

And while she loves him, she sometimes grieves for her daughter.

“You have to realize it’s like dealing with the loss of a child,” she explains. “There is a real sense of mourning.”

Parents often undergo what is called the Kübler-Ross five stages of grief, which include denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. Not everyone experiences all five stages, or in any particular order. But the ultimate goal is the same: acceptance.

Writer and psychotherapist Felicia Levine is a licensed clinical social worker and board-certified transgender care therapist with a Ph.D. in clinical sexology. She has a private practice in Deerfield Beach and co-facilitates transgender support groups in Boca Raton and Wilton Manors, as well as a support group in Deerfield Beach specifically for parents of trans kids. Her website is felicialevinelcsw.com.

Lead photo by Eduardo Schneider

Trans Basics

Transgender (or trans) is an umbrella term that describes people whose gender identities are different from the ones with which they are assigned at birth. Simply put, their biological bodies don’t match their gender identities (the gender they feel inside). Trans people often describe feeling “trapped in the wrong body,” which results in gender dysphoria, the clinically significant distress that occurs when body and gender don’t align. Kids are especially vulnerable when they reach puberty and begin developing secondary sex characteristics of what they feel is the wrong gender.

There are many variations on the gender spectrum:

If a person’s biological body and gender identity match, they’re cisgender.

A biological female who identifies as male is a transgender male (pronouns he/him).

A biological male who identifies as female is a transgender female (pronouns she/her).

A person who identifies as neither fully male nor female—no matter their anatomy—is nonbinary, also described as gender nonconforming, gender variant or genderqueer (pronouns they/them or ze/xe).

Gender transition is the process people undergo to start living in their identified gender; this may include social, physical, medical and legal steps.

Local Resources

Compass Community Center in Lake Worth offers trans services, including a weekly transgender youth group for ages 12-18 and an “Authentically YOUth” support group for trans children and their families. Visit compassglcc.com.

The Pride Center at Equality Park offers weekly and monthly trans support groups. Parents/family members/allies are welcome to meetings held on the fourth Friday of the month. Visit pridecenterflorida.org/calendars.

SunServe in Wilton Manors offers trans services, including the “Different Drummer” family group for kids ages 3-12 and their parents, and “SOFFA” for significant others, family, friends and allies of trans individuals. Visit sunserve.org.

Yes Institute in Miami offers education and advocacy throughout schools, businesses and communities worldwide, as well as resources and support for families. Visit yesinstitute.org.