Melody Erez admits that she often takes her work home with her. Like others in her profession, the speech therapist notes that she thinks about her patients’ cases after meeting with them—how she can try something different to help them improve. But she doesn’t mind.

“I always wanted to help people, and I feel like [speech therapy] lets me help people the most,” she says.

Erez actually didn’t hear of speech therapy until her mother had a stroke and had to see a therapist to “gradually get her words back.” Knowing she could influence lives with this newfound career, the high school art teacher earned a master’s degree in speech-language pathology from Nova Southeastern University and started working as a speech therapist in schools. Though she loved her work, Erez found she wanted to explore what it would be like to work in a setting where she could make individual plans for children and get to know patients better.

With the help of her husband, the Coral Springs resident choose a spot in Coconut Creek to open Acorn and Oak Speech Therapy, where she has practiced for two years. There, Erez, who is certified by the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, sees children with speech disorders as well as adults affected by strokes and brain damage.

The name Acorn and Oak represents patients’ growth as well as Erez’s desire to help people of all ages (from “acorns” to “oaks”), grounded on the belief that everyone can improve and on her driving force to find what motivates them.

“I have to find that trigger—that motivator, and that’s actually kind of fun for me. I like problem-solving,” Erez says. “I like thinking about what gets that person excited and trying to have it consistently for them. For some kids, that’s crafts; for some kids, they need to be moving … and, for other kids, they just need to be quiet and color while they’re saying their words.”

As back-to-school time arrives, Coconut Creek Lifestyle met with Erez to learn what parents should know about speech therapy and working with schools to help children succeed.

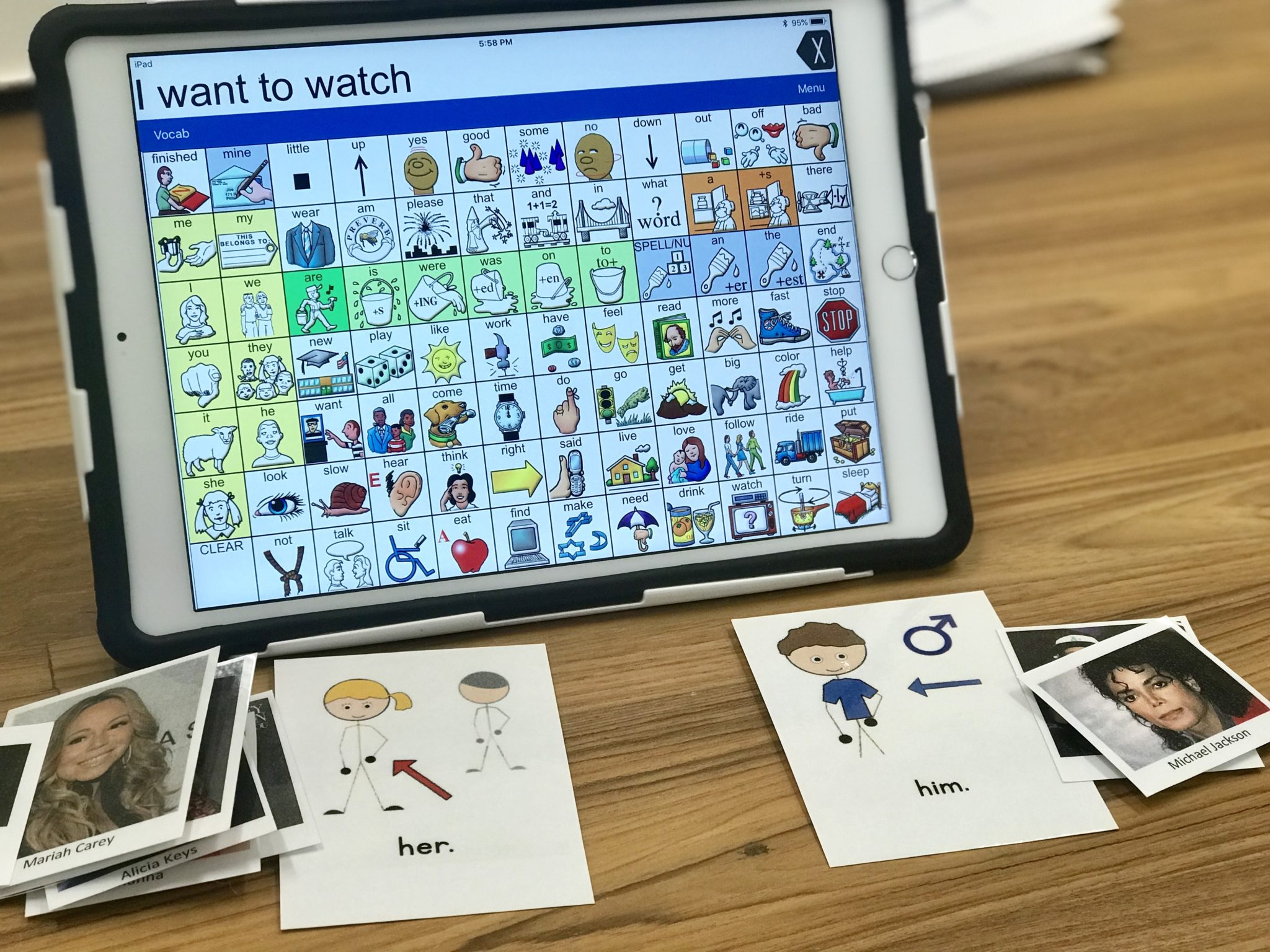

Speech therapists help people with speech disorders such as a stutter or speech-sound errors (making the “w” sound for the “r” or having airflow issues when saying “z,” “s,” “sh” or “ch”). They also help those who cannot communicate verbally to use alternative communication devices. In addition, they assist children who have difficulty with speaking, writing, reading comprehension or social skills and help them sound out consonants and vowels. Some also work on feeding/swallowing disorders.

Special needs and speech errors

The reason for speech disorders might be unknown or can be genetic, such as stuttering. In addition, speech disorders may stem from a special need—but they’re not always connected.

“In terms of speech-sound errors, it may be that they just have those [errors] and they have no other diagnosis. [There’s] not always an underlying condition,” Erez says. “But there are some underlying conditions that do often need speech therapy. A child with Down syndrome probably needs speech therapy because their language is limited and they probably have speech-sound errors.”

Determining the need

Erez notes that identifying a need for speech therapy usually starts with parents noticing their child is not talking or using as many words as other children. This might result in a child acting out to communicate. Or a teacher might notice the child is having a hard time talking or being understood by classmates. Early intervention and evaluation are key, as these children might stop communicating and socially withdraw.

“I would tell a parent, if they’re not sure, to call a speech therapist,” Erez says. “A lot of people like me do a phone consultation, and I help them understand based off what they’re telling me if it sounds like they might need to be tested.”

Erez uses standard tests to compare the child to others of the same age and gauge the severity of the speech disorder. Then, she creates goals for the patient, identifying issues expected to be treated in a limited time. Doctors are informed that the child is being treated. Children come in a few times a week, progressing until they master their goals. The goals might also change to fit the child.

“With speech-sound errors, usually you’re working until you resolve them—until the child is speaking without errors or at optimal ability,” Erez says.

“With speech-sound errors, usually you’re working until you resolve them—until the child is speaking without errors or at optimal ability,” Erez says.

Preparing for school

Whether a child has special needs or a speech disorder, Erez suggests introducing children to teachers with a document listing their likes, dislikes, learning style, challenges with fine or gross motor skills, etc.

“For example, if your child has autism, [they] might have sensory needs,” Erez says. “Maybe they don’t like anything wet, and the teacher needs to know that because they’re going to use glue. Or maybe they need to know that your kid works best in certain period-of-minute intervals, and then they need a reward later.”

Working together

At school, students who receive specialized services have individualized education plans—formal documents that state goals, accommodations and modifications. Erez helps parents understand accommodations (changes to help students with testing) and modifications (changes made to the everyday working environment), suggesting which of these to include in an IEP based on her observations. For example, a child with dyslexia might receive an accommodation to listen to audio files instead of reading.

Erez also works with schools’ exceptional student education departments to add information to a child’s IEP, such as the technique she’s using to treat a speech disorder or what she’s noticed about the child’s learning style.

About exceptional children

Erez finds many parents don’t know about a demographic known as twice exceptional children, or 2E. These children are gifted but also have a diagnosis. A gifted child might have speech articulation problems or have difficulty reading social cues. This can lead to the child being perceived as uncooperative when specific help is needed.

“I have some very young kids [who are] what we call ‘hyperlexic’—they can read at a very young age. … But maybe those same kids have social challenges, or trouble with sequencing, so if I asked them to tell me the steps that make a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, they can’t do it,” Erez says. “So they’re advanced in some ways, and they need help in others.”

Erez recommends parents have students tested for being gifted if they see exceptional abilities and then communicate with the school as 2E children need both an EP (education plan) and IEP to make sure they stay motivated and get support for their challenges.