He doesn’t mind being knee-deep in algae. In fact, scientist H. Dail Laughinghouse will tell you it’s where he feels most comfortable. But Laughinghouse admits to having his “Oh, my gosh. This is what I do for a living?” moments from time to time.

He doesn’t mind being knee-deep in algae. In fact, scientist H. Dail Laughinghouse will tell you it’s where he feels most comfortable. But Laughinghouse admits to having his “Oh, my gosh. This is what I do for a living?” moments from time to time.

“So, there I was at Lion Country Safari [in Loxahatchee] sitting in the moat with chimpanzees and I thought, ‘Well, this isn’t somewhere I would ever dream I would be.’ ”

The Coconut Creek resident was there because the park’s monkeys and apes had developed cancer. “They were wondering if the water quality was contributing to their bad health.”

That water quality might have included harmful algal blooms, toxic formations that come from a rapid increase in the population of algae. This is what Laughinghouse lives for—a passion that has led him around the world over the past 15 years to study the effects of algal blooms. “South America, Central America and Europe. It’s a worldwide problem,” he says. Before arriving in Florida three years ago, he conducted a two-year study in the Norwegian Arctic. “Guess what the average temperature was? Forty degrees below 0.”

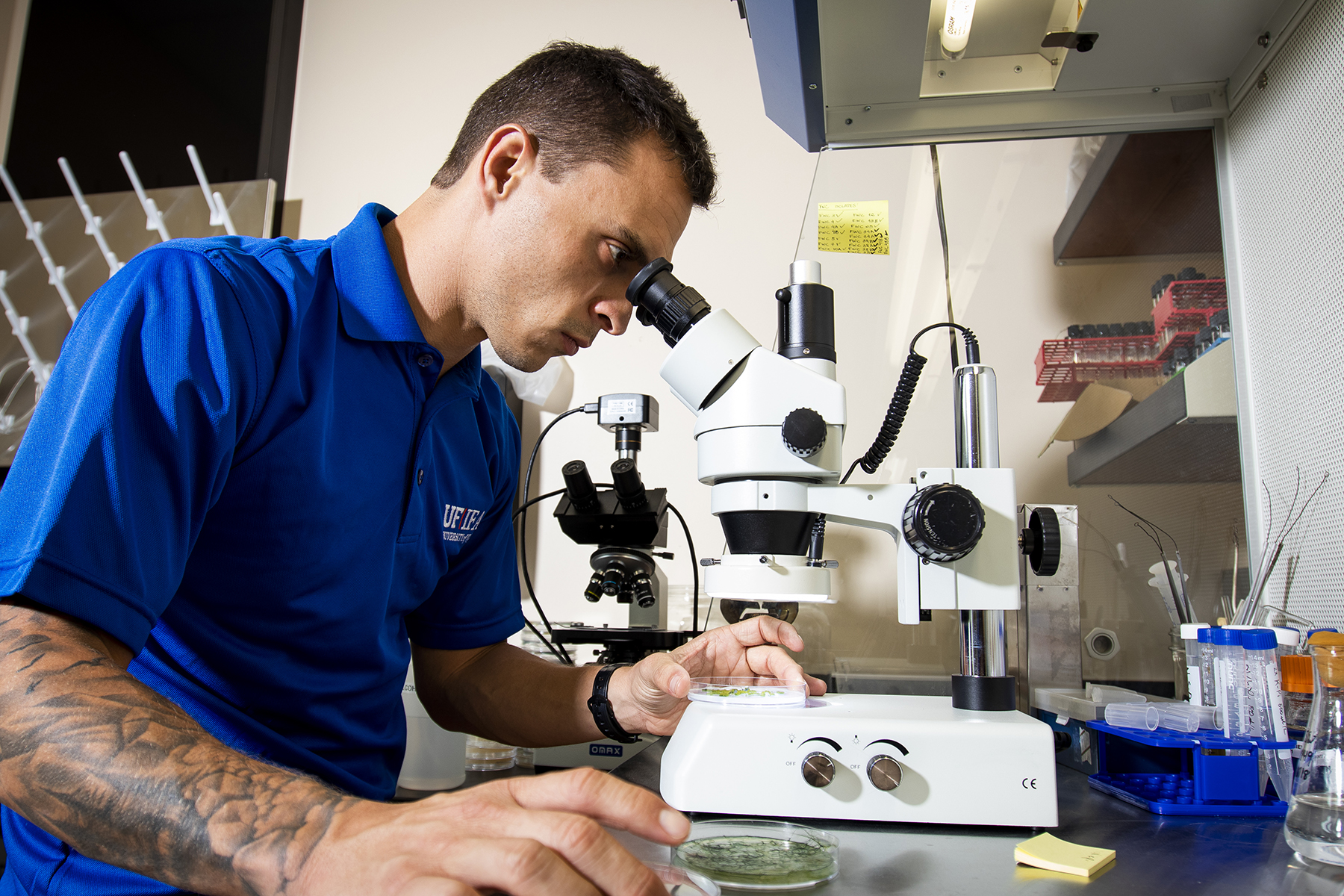

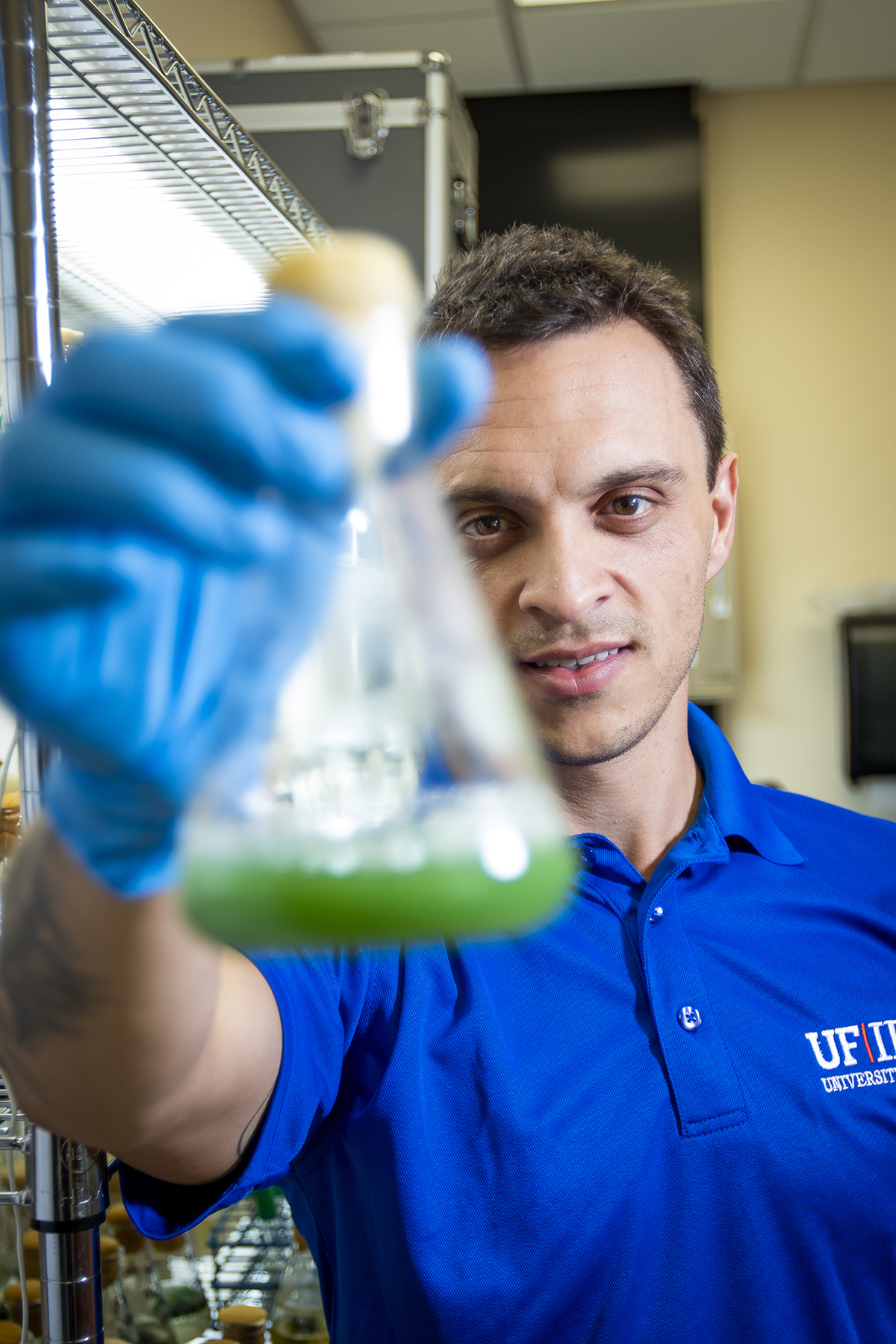

It’s obvious Laughinghouse will go to great extents for algal blooms. In the Laughinghouse Lab at the University of Florida/Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Center, located in Davie, he has more than 400 different strains in his culture collection. He also studies what triggers algal blooms as well as algae control.

You won’t find the assistant professor in applied phycology lecturing in a classroom. “I don’t teach Biology 101,” he says—although he does work with master’s and doctoral students. “My formal appointment here is that 30 percent of my time is devoted to working with county agencies and other forums to get this information out to everyone,” he says. “To educate the public.”

When he was an undergraduate majoring in biological sciences at Brazil’s Universidade de Santa Cruz do Sul in his hometown of Santa Cruz do Sul, he had received a small grant to research fungi. He happened upon a workshop being conducted by an expert who was giving a talk: “Algae as Bioindicators of Water Quality.” He decided to check it out as he was interested in water and different organisms.

That workshop brought up for him how affected Brazil was years earlier with a public health crisis when algae had sickened people at a medical clinic.

Algal blooms weren’t much on the radar as a cause of global concern, Laughinghouse recalls. It was 1996, he says, when what became known as Caruaru syndrome got international attention. In this case, 116 people who had received routine treatment at a hemodialysis clinic were exposed to cyanotoxins from water that had not been treated, filtered or chlorinated. One hundred developed acute liver failure. “The microcystins were found in the water as well as the blood and livers of the patients.” Laughinghouse says it was a wakeup call to the world. “That’s when the World Health Organization really started to care about these blooms,” he says.

Learning more about algal blooms combined so many facets of his interests that, after that workshop, he was hooked.

“I realized how nutrients in water, changes in climate and our direct effect on water have an impact on public health. That grabbed my human health interest together with interest in environments. I wanted to know more about these organisms. ”

His interest bordered, and still does, on obsession. He remembers after his introduction to algae, he couldn’t get enough of trying to figure out these living organisms that have been around for 3.5 billion years. Laughinghouse, who holds a doctorate in estuarine and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland, says there is so much to discover that the research could continue another billion years.

For the layperson, trying to understand algal bloom is complicated. There’s a lot of scientific terminology—words like microcystins and cyanobacteria—but the bottom line is that the algae gets so thick in water that it causes contamination, killing fish and marine life and spreading toxic poisons into the water and the air. Algal blooms are an “urgent threat” threat to the ecosystem, he says.

Remember the red tide?

Laughinghouse recalls 2011, when Lake Erie experienced a harmful algal bloom, and then the levels showed up in drinking water tests in August 2014 leaving 400,000 people in Toledo, Ohio, without a water supply for days.

Closer to home, most everyone in South Florida remembers a year ago in October when “red tide” covered beaches in Fort Lauderdale. Red tide is one of the most well-known harmful algal blooms. Not only does it kill fish, but it can also be absorbed by shellfish or ingested by fish, putting it into the human food chain if the fish are eaten by people. Red tide also can cause respiratory problems as well as it washes up on beaches, spreading toxic poison into the air.

Blue-green algae is one of Laughinghouse’s focuses. These are cyanobacteria blooms, a microscopic bacterium found in freshwater lakes, streams, canals, ponds and standing water.

“They produce a group of toxins known as a microcystin. Exposure can lead to problems like liver failure, tumors, jaundice and headaches,” he says. “Neurotoxins in the blooms can cause dizziness and paralysis and other neurological problems.”

This isn’t to say that all algal blooms are bad. In fact, Laughinghouse says some are vital because the tiny plants provide food for fish in the ocean. “It’s when there’s an imbalance that it gets out of control.”

He likens it to drinking alcohol. “I like a bloody Mary now and then—it makes you feel happy. The aquatic system nutrients are that way,” he says. “The nutrients [mostly phosphorous and nitrogen] are necessary. However, if you have too much alcohol, you start feeling sick. So, too many nutrients in the water, then the water starts getting sick.”

For anyone who questions climate change, Laughinghouse says the algal bloom is direct evidence that it’s increasingly becoming an ideal world for the organisms. “What’s happening is you have higher light and higher temperatures, which allow for the proliferation of algal bloom,” he says. “Then you get this input of nutrients from land-use change—yards and gardens, agricultural, sewage, septic tanks. Everything contributes. The thing is, we are a huge population on the planet. People like to point fingers, but I say point fingers to yourself. Humans eat and then they produce excrement. Sewage. What kind of car do you drive? That makes a difference in the climate. Do you use electricity? Yes, you do. You make the impact.”

The Good and the Bad

Laughinghouse emphasizes, however, that when properly managed, the blooms can be beneficial. “We’re discovering more and more every day,” he says. “They have bioactive compounds that can be a boon to public health.”

He cites the use of the algae for pharmacology such as nutraceuticals, and in chemistry as biofuel. That’s what fascinates Laughinghouse about his field of study.

“These beings have been here 3.5 billion years. Not million—billion,” he says. “They were here before we came, and they’ve stayed around when so many things have become extinct. I’ve seen them thrive under ice in the Arctic and in the geothermal springs in the geysers of Yellowstone Park. They have this ability to survive and we don’t understand yet what they have that makes them so resilient. They’ve existed in so many different environments—in soil, water, trees, on the back hairs of polar bears and on the shells of turtles. They create terrible toxins that can cause death, but they also have compounds that are anti-cancer and anti-tumor.”

While he continues on his quest to learn more, Florida offers him plenty of opportunity for studying. In fact, he takes his work home with him. “Sometimes you’ll see me at Banyan Bay [his apartment complex in Coconut Creek], or some of my associates, back at a pond. I’ve told the management company to not be alarmed. If you see people wearing latex gloves and collecting samples, it’s just us.”

Lab photos by Eduardo Schneider

Become a VAMP

In St. Lucie and Martin counties, Laughinghouse was instrumental in developing UF/IFAS’s VAMP, the Volunteer Algae Monitoring Program. He’s considering kicking off the Broward segment in Coconut Creek. Volunteers will learn how to sample the waters in their neighborhoods and then send them for testing to the Laughinghouse Lab.

“We have these trained scientists, water stewards, that are helping us, and they are getting a better understanding of what’s going on in their community waterways,” he says.

To find out more, contact

Laughinghouse at 954.577.6382 or hdail.laughinghouse@gmail.com.