It’s late in a riveting and revealing interview with Kate Mulgrew when the award-winning actress who brings such nuance to her portrayal of “Red” Reznikov on “Orange is the New Black” unexpectedly pivots. She wants to correct a misconception about the more-than-three-year journey that resulted in her recently released book, How to Forget: A Daughter’s Memoir.

It’s late in a riveting and revealing interview with Kate Mulgrew when the award-winning actress who brings such nuance to her portrayal of “Red” Reznikov on “Orange is the New Black” unexpectedly pivots. She wants to correct a misconception about the more-than-three-year journey that resulted in her recently released book, How to Forget: A Daughter’s Memoir.

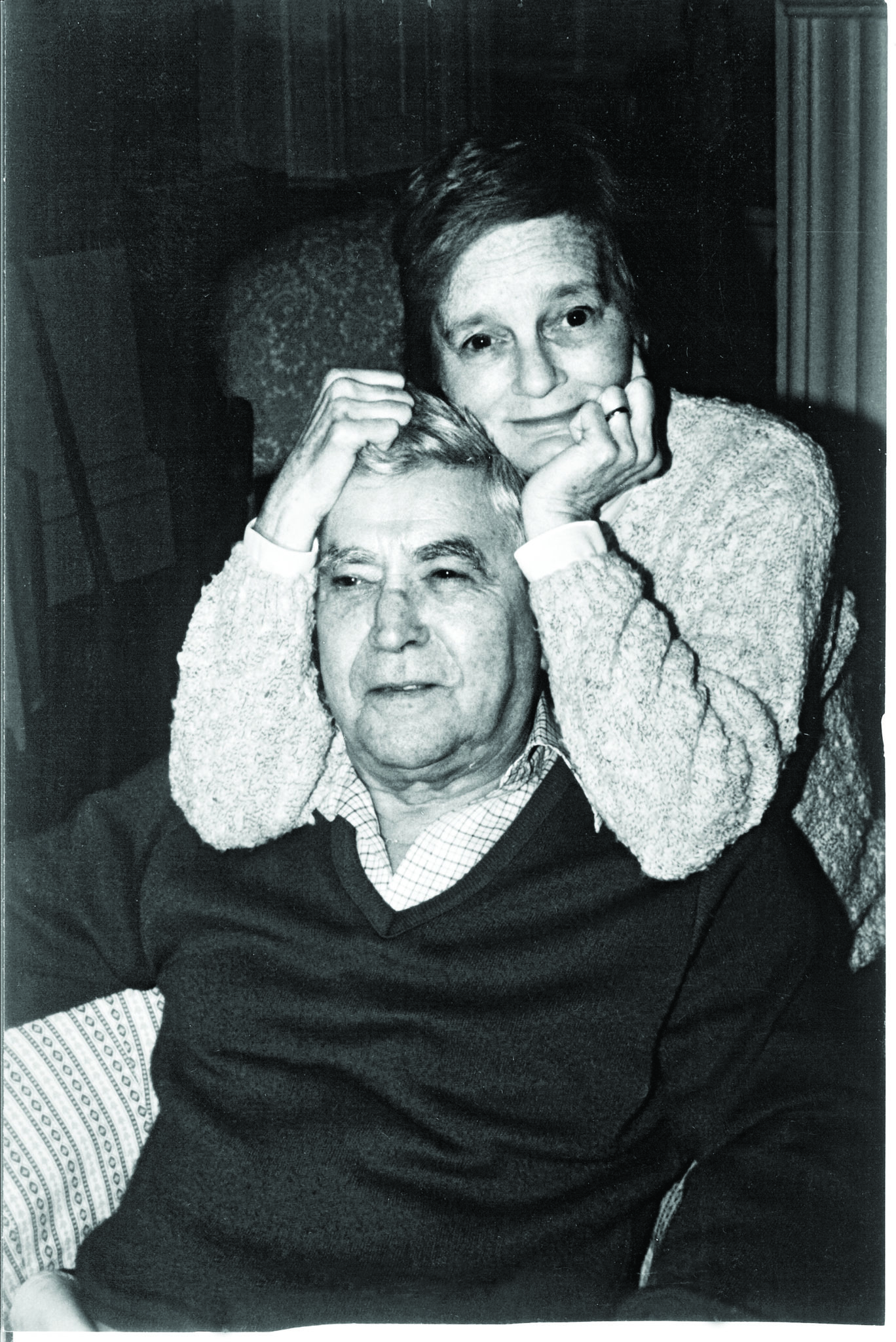

In it, the native of Dubuque, Iowa, reflects on a two-year period more than a decade ago during which she returned home for the final days of her cancer-stricken father, Tom, and for a long and heart-wrenching goodbye to her mother, Joan, who died in 2006 of Alzheimer’s disease. Along the way, Mulgrew writes candidly and eloquently about the joys, frustrations and complexities of her relationships with both parents, creating a narrative that’s filled with deep examination, startling revelations and great affection.

But, as the 64-year-old mother of three notes, the process that resulted in her second memoir (following Born With Teeth in 2015) was anything but cathartic.

“It’s not therapeutic to write about your parents’ deaths and their lives,” says Mulgrew, who fans of “Star Trek” recall as the franchise’s first female captain in a leading role (Kathryn Janeway on “Star Trek: Voyager” from 1995 to 2001). “It’s an excavation. It’s an archeological dig. That’s really what it felt like. Every day was another day of going deeper into something I knew was going to be difficult.

“Catharsis comes if you’re writing about a love affair that went wrong, or something like that. But I don’t know that catharsis can ever come when it’s been resolved by the deaths of two people who you loved deeply. In particular, when it involves something as pernicious as Alzheimer’s disease.”

It’s a memoir that will resonate with readers in South Florida who’ve lived through a parent’s disease and death—and one that Mulgrew was gracious enough to speak about with Lifestyle.

You write so beautifully about your opportunity to have “the talk”—in this case, a fireside chat with your father on the night he discovered he had only weeks to live. Did you say everything that you wanted to say—and hear everything that you wanted to hear—that night?

From the moment my brother called me in West Palm Beach [where Mulgrew, in 2004, was performing her one-woman play, “Tea at Five,” based on Katherine Hepburn’s memoir], I was working on the “curriculum,” so to speak. I had speculated on my way to Dubuque for the meeting with the doctor that the diagnosis would be terminal. And I was hoping I would have that night.

The questions that came to me were indeed the profound and philosophical questions that had been left hanging between us for years. If we shared some vodka in front of the warm fire, and death was hanging over him, maybe he would [speak openly]. And he did. I was delighted that he was present to me that night. It was all I could have asked for and more.

Most siblings and most children don’t get this opportunity. First of all, they don’t ask for it. Nobody wants to say, “You’re dying, this is it.” But I did. I asked. And he answered absolutely directly—I don’t welcome death, he said, but I don’t fear it. So, let’s get down to business.

About your father, his upbringing and the post-World War II generation of parents, you write, “Fathers like you are not to be known. Isn’t that why you are so loved?” Can you unpack some of what’s folded into that sentiment?

My father was Irish-Catholic, a member of the Greatest Generation. They were soldiers. They were brought up with a certain kind of courage and stoicism and privacy that neither you nor I know anything about. It stamped that generation. It was a time when people did not reveal themselves; it was considered in poor taste—and it showed weakness. Particularly in my father’s case, it would indicate a kind of garrulousness or even an ignorance.

So, in his withholding—one might even say, in his recalcitrance—there was great power. By being silent, they could rule the fort. Everything was kept inside. It’s no wonder he was riddled with cancer in the end, not to mention the fact that he smoked two packs of Pall Malls a day. But they held it all in. That’s who they were.

And, boy, he had us in the palm of his hand. He was 5-foot-6, but he was huge. When that car pulled into the driveway at night and the back door slammed shut, we would just scatter. He had an intensity and a presence that was unparalleled in my experience.

If you’re on the wrong side of that silence, it can produce great hurt. That pain is tangible when you write about the indifference he had toward your career. How did that disappointment impact you, and why do you think your father felt that way?

Of course, I had to deal with it. I had to learn how to dance around it. I had to learn how to deflect and be charming. I never complained, I never wept, and I never stood up to him in a petulant manner.

But when he was dying, I asked him. I was quite a successful actress at that time. “Why did you show such disdain for my work, Dad?” He told me that he thought it was goofy.

I didn’t buy it then, and I don’t buy it now. I think there was resentment there; I don’t know why. Maybe because my mother loved it so much. And she was often taken away from him because of it. Early in my career, I was financially successful, so I could pay for her to come [and visit Mulgrew or see her perform]. I think that really rubbed him the wrong way, got to his pride.

It doesn’t haunt me. It doesn’t pack a terribly wild punch today. But I write the truth in the book. It always stung. Especially when the sobriquets began to change from “Kitten,” which I adored, to “Big Shot” and “Hollywood.” That’s when I knew he was angry and resentful.

There was so much between you and your mother. She was your friend and the biggest supporter of your dream to act. You were her confidant involving her laments and her secrets. As Alzheimer’s sets in, did something from that mosaic rise above the rest?

That I promised to be her mother [when the time came].

That saved me in the end, because that’s the way I could see her out. Having to say goodbye to my mother in that way was more harrowing and more awful than I could write in any book. She was the great force and love of my life. She shaped me and defined me in many ways. And ours was an unusual and dimensional relationship. I made that promise to her when I was 14, and I was going to keep it.

To the best of my ability, this woman would go out with as much comfort and love as [the family] could provide her.

This is something I would advocate for [when dealing with a parent diagnosed with Alzheimer’s]. As sons and daughters, we have to get tough. Someone has to take over. That person should be the one with seniority or authority in the family and [if possible] some degree of means. That was me. I had my mother sign the health care guardianship; I put everything in place, and I told my father, you do not have a leg to stand on. I’ve got the caregiver, she’s going to live in the house, and here’s the doctor to explain to you that this must be the way it is.

I hoped against hope that my father would be able to see this for what it was. But he never said another word to me about it. That was the final shutting of a door, and it broke my heart. But I had to overstep my bounds. It was so clear that there was something wrong with my mother.

What makes Alzheimer’s so insidious for the loved ones dealing with the transformation?

A poison settles [over the relationships with your siblings] because the letting go is so very hard to do. And everyone wants to do it individually. But there’s no time or way to arrange for that because she’s no longer cognizant. So, all kinds of things come to the surface. Resentment percolates. There are deep feelings of great loss and almost a kind of muted howl from some of my siblings about what they would never have.

[Her mother was] the hapless pawn on this awful chess board. And we were just as hapless because we knew there was nothing to be done to help her in the end.

She’s been given a death sentence. So, nobody wants to complain about it and show any kind of petulance regarding her Alzheimer’s. But it did manifest itself at certain times. The finger pointing. The things that lie dormant that rise to the surface. There was a lot of that. There were a couple of years where it was very intense.

How have your brothers and sisters received the book?

[Her brother and the oldest of the siblings] Joe, I suspect, has some problems because he’s a private person, and he’s featured in part one because of his deep and important relationship with my father. He misses him, and he loved him. And I understand that he would resent my illustrating that on paper when it’s his relationship with Dad. But I asked him, and he gave me his blessing. So, there you have it.

It’s a memoir; these are my memories, and they’re deeply subjective. You can’t win ’em all.

Kate Mulgrew photo by Max Schwartz