Helen Witty remembers the day she heard sirens wailing down her quiet neighborhood block in Pinecrest. It was a clear June afternoon when her daughter, 16-year-old Helen Marie, had left the house to go inline skating on a bike path near the family’s home, something she often did after school.

Helen Witty remembers the day she heard sirens wailing down her quiet neighborhood block in Pinecrest. It was a clear June afternoon when her daughter, 16-year-old Helen Marie, had left the house to go inline skating on a bike path near the family’s home, something she often did after school.

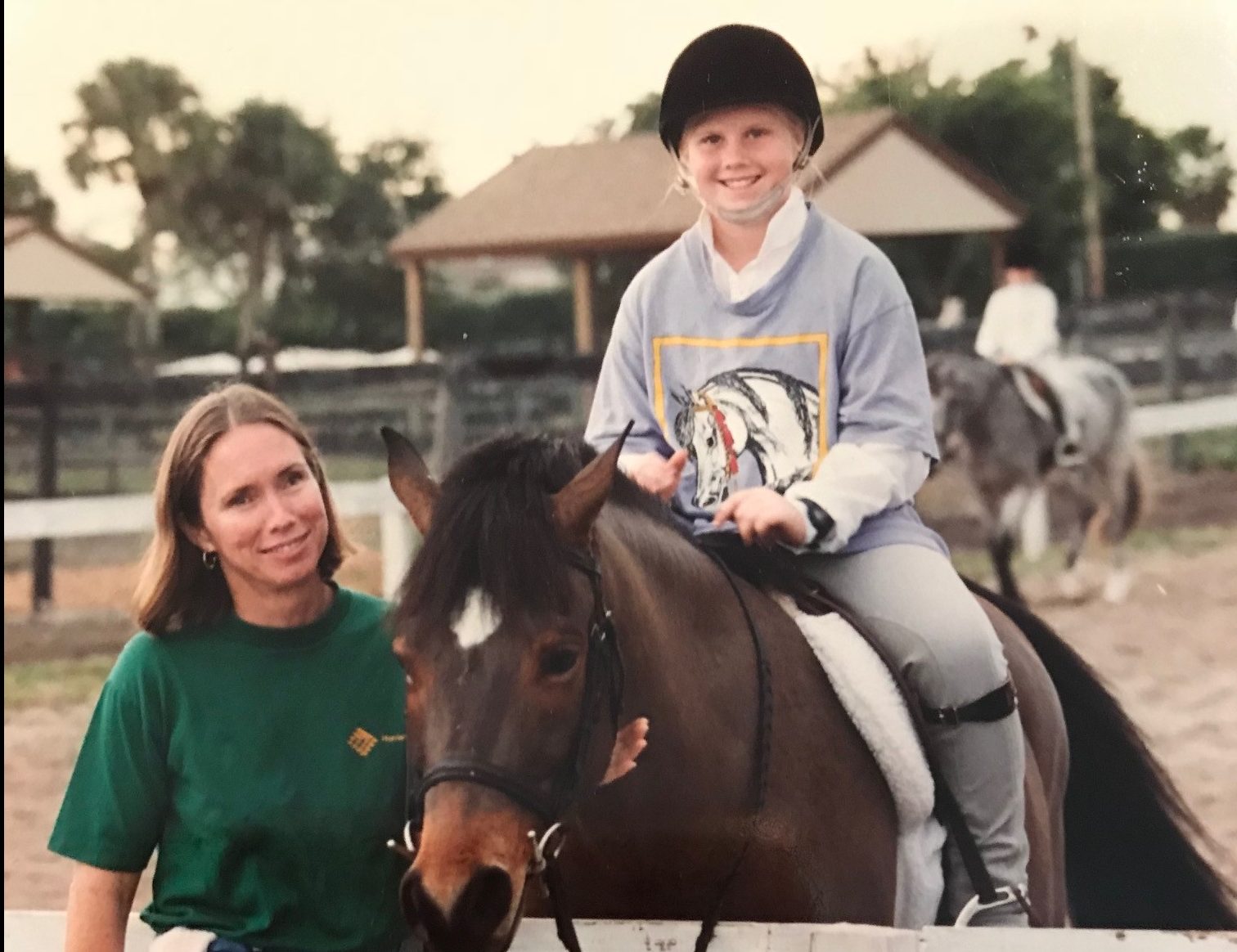

“I had just gotten home from a trip, and Helen walked through the door from school and told me how nervous she was about a play she was directing the next day,” Witty remembers. “So off she went Rollerblading to ease her nerves. She blew me a kiss and said, ‘I’ll be right back, and I love you.’ ”

As Helen glided down the driveway, Witty and Helen’s brother, John, stood on the porch and waved goodbye.

“I remember saying ‘I’ll see you in a little bit,’ ” Witty says. “But I never saw her again.”

Once Witty heard the sirens, she thought “how glad she was that Helen was on Rollerblades instead of driving.” But more than an hour later, when Helen still wasn’t home, the family started to worry.

“My husband went out looking for her,” Witty says. “But when he didn’t come home either, I knew something terrible happened. I called the Pinecrest police department, but they wouldn’t tell me much. Once he returned, his mouth was moving but no sound was coming out. That’s when a police officer, who was with him, said, ‘I’m very sorry, but there has been a horrible crash and your daughter is dead.’

“I remember being upset at her and wondering why she was Rollerblading in the street,” Witty says. “But then I found out the car swerved into the bike path, and ultimately we learned the driver was drunk, drugged and on a cellphone.”

Shattered by the sudden loss, Witty found hope through Mothers Against Drunk Driving, the nonprofit organization founded in 1980, which campaigns to end drunk driving and supports survivors of such accidents. This year, almost 20 years after her daughter’s death, Witty has been appointed president; she will speak with lawmakers around the nation to advocate for victims in hopes of helping to end drunk driving.

Lifestyle spoke to Witty about her involvement with MADD and the organization’s accomplishments.

How did MADD help you cope with your daughter’s death?

Less than a month after [it happened], I woke up one morning and said to myself, “The bad news is I’m going to live, and I don’t know how to live this way.” Everything I thought would be in my future was blown up. My whole life was upside down. I told myself that if I couldn’t figure out how to live again, this would kill me. At the time, I had a friend who knew the president of our local MADD chapter. She told me to call her when I was ready, and now the rest is history. I spent 11 years as a volunteer victim advocate, helping survivors and victims navigate court proceedings. I also would go everywhere and anywhere MADD asked to share my story. I would stand up and talk about my daughter, and then sit down and cry.

What is so unbelievable about MADD is, I remember sitting in a room full of members and looking across the room to a woman smiling and laughing. I thought maybe one day I’d be able to smile, too. And now here I am. I was compelled to continue my involvement with MADD, which is why I spent seven years as a staff member facilitating prevention programs in South Florida and also trained in MADD’s National Death Notification curriculum, which I presented to law enforcement agencies throughout the state.

Where do you see MADD’s focus today?

We have always been and remain focused on alcohol. Many think alcohol isn’t the problem, but that’s not true. Phone deaths are nowhere near alcohol-related deaths. What’s important to note is MADD isn’t against alcohol; we’re just against drinking and driving.

As president, I want to offer hope and encouragement to those personally impacted by this senseless crime. Because drunk-driving deaths have increased over the last two years, it is vital to work with federal and state legislators to strengthen life-saving laws. Florida is third in the nation for fatalities. Currently, there are 32 states and [Washington,] D.C., which have all-offender ignition interlock laws, which means a convicted drunk driver must have a device in his or her car for a certain amount of time to determine sobriety before the car starts. But Florida doesn’t have this.

What must be done to continue to reduce the crime of drunk driving?

If you drink, don’t drive. If you drive, don’t drink. It’s that simple, until you get someone who thinks they’re fine and can drive. That’s the thing about these drugs: They make you feel fine. But you don’t want to be the person facing a grieving family in court and going to prison. No one intends to hurt someone—that’s the difficult part about this crime. That’s why I continue to lobby legislators in Miami and Tallahassee for tougher drunk-driving laws. I also believe in the importance of requiring ignition interlocks for all offenders, and I advocate for high-visibility law enforcement, such as sobriety checkpoints. I also urge parents to talk to their teens about not drinking alcohol until 21.

What are some MADD initiatives and efforts that you’ve been personally involved in?

I joined the bereaved family and friends of Aaron Cohen to help pass the Life Protection Act (in his name) following his 2012 death by a hit-and-run driver. Now, if a driver flees the scene of a fatality and doesn’t stop to render aid or call 911, the driver will be given the same penalty as a drunk driver who causes a fatality. This passed unanimously in Tallahassee. I’ve also had the opportunity to work with wonderful volunteers for the last 10 years for Walk Like MADD, which is our only fundraising event. The funds generated each year keep our mission strong in Miami.

What’s something the public probably does not know about MADD?

People tell us often that MADD has encouraged them to use Uber instead of drive. That’s a big win for me and the organization. I worked in Miami-Dade County schools for years, and I still hear individual stories from teachers and students on good decisions being made. Those are the golden moments. Otherwise, it’s important for the public to know we support victims, and we’re not just an angry group of middle-aged women. We are made up of men and women, brothers and sisters, and families. It’s horrifying, it’s random—and it affects everyone at every age, no matter race, financial situation, or any other factor. And the reality is we know how to fix this crime.

How does it feel to now lead the organization?

In those early, desolate years, I never imagined being in this position. Honestly, I couldn’t imagine being alive. I am honored to add my voice to those who have come before me. Since 1980, due to MADD’s work, the number of drunk-driving deaths has been cut in half. I am among the nearly 1 million victims and survivors MADD has served. It’s still hard to believe I will be representing them across the nation for the next two years. It’s a true privilege. Because Helen Marie was so full of life, I can hear her saying, “Mother, say something. Mother, do something.” MADD has provided the platform for me to do just that. I am grateful.