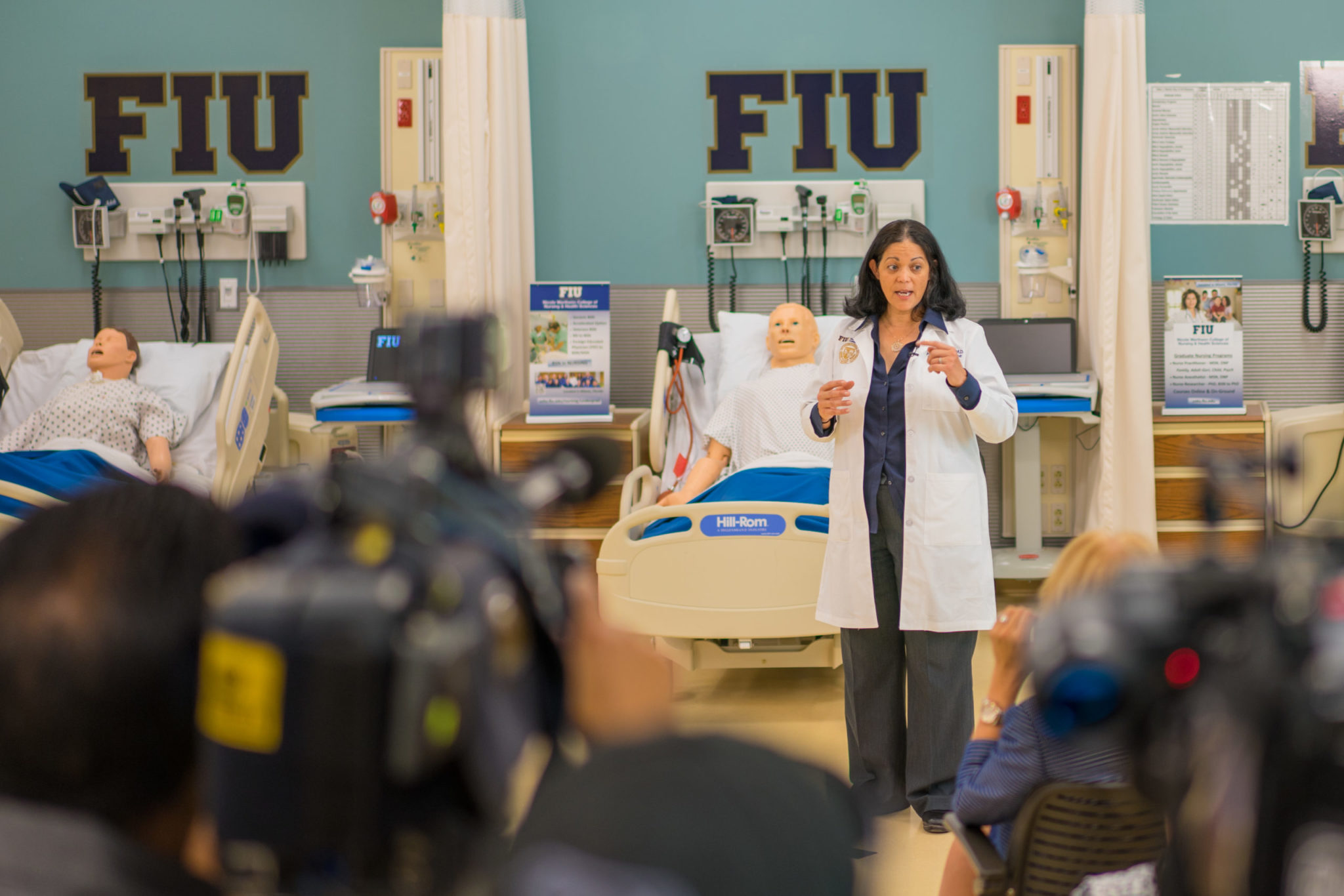

Aileen Marty, M.D., remembers where she was when she first learned about COVID-19. It was mid-January 2020. The infectious disease physician and professor of infectious disease at Florida International University’s Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine was in the Middle East. She was with colleagues from the World Health Organization’s Verification and Inspection Commission. They were invited by Qatar’s ministry of public health as the country prepared for its 2022 FIFA World Cup.

The experts in mass-gathering medicine were strategizing how to manage the millions of people from all over the globe who would be attending the World Cup. Such large-scale events always have a health preparation component, and the area of mass-gathering medicine explores, among other things, the inherent risks when that many people descend on one city. For starters, there’s a higher incidence of injury, illness and catastrophic accidents—plus, the possibility of a mass attack looms.

“Anytime you are preparing for a mass gathering, you look around the world for what could cause problems,” Marty says. “Of course, we were also, at the time, considering what preparations were needed for the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo [which have since been moved to July 2021].

“So,” the graduate of the University of Miami’s Miller School of Medicine recalls, “we receive this information about what was going on in China. I wound up giving my first assessment of the novel coronavirus on Jan. 17 in Qatar to a room full of some 3,000 people [the outbreak had started to manifest in China a few weeks before Marty’s first assessment]. There were very few cases. The Chinese Center for Disease Control had only seen about 44 patients by the end of December. That’s it.”

Three days after Marty’s presentation in Qatar (Jan. 20), the United States confirmed its first case of coronavirus.

“Those of us who have been interested in coronaviruses for decades recognized what one of our colleagues had said back in 2007,” Marty says. “SARS was a ticking time bomb.”

SARS-CoV-2 is the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19. This novel CoV was found to be similar to what was responsible for the SARS pandemic in 2002. On Jan. 30, the World Health Organization declared the novel coronavirus a public health emergency of international concern.

Since then, Marty has become a regular on national television as an expert on the pandemic—and with good reason. She’s traveled the world to study and treat tropical medicine and infectious disease, including a 25-year career with the U.S. Navy, where she specialized in tropical medicine. She also was chief of infectious disease at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, one of many esteemed posts she’s held over the years.

Back in 2014, the WHO notified Marty that she was needed in Nigeria, where a new outbreak of Ebola was threatening more than west Africa. It was here that Marty’s expertise gained national attention. She spent 31 days there in a response that is now historic, with only eight deaths and 20 total cases before WHO declared the country free of Ebola on Oct. 20, 2014. How was that outbreak stopped in its tracks?

“If you can break the transmission, you can control the outbreak,” Marty says.

If there is a way to contain something like deadly Ebola, why couldn’t COVID-19 have the same immediate shutdown?

If there is a way to contain something like deadly Ebola, why couldn’t COVID-19 have the same immediate shutdown?

The World Health Organization’s role is to alert nations to a PHEIC, a public health emergency of international concern, which they did on Jan. 30. By international law, this is when governments are supposed to start acting. This is the time that leaders should immediately put their pandemic plans in place.

[NOTE: The WHO defines a PHEIC as an “extraordinary event” that “constitute[s] a public health risk to other States through the international spread of disease” and “potentially require[s] a coordinated international response.” Since that framework was defined in 2005—two years after another coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome, spread through China—it has been used only six times: for outbreaks of “swine flu” in 2009, polio in 2014, Ebola in 2014, Zika virus in 2016, Ebola in 2019 and, now, coronavirus in 2020. It is meant to mobilize international response to an outbreak.]

On March 11, the World Health Organization declared the novel coronavirus outbreak a global pandemic because they were fed up with world leaders not acting. [Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said at the time that the WHO was “deeply concerned by the alarming levels of spread and severity and by the alarming levels of inaction.”] An epidemic is a large outbreak; a pandemic means it has crossed borders. As soon as there is community spread outside of the original outbreak zone, it is a pandemic. The fact that nations didn’t respond to the PHEIC, that’s the fault of each nation that didn’t respond.

Why was the United States unprepared?

We had a leader who wasn’t basing decisions and responses on science but on personal gut feeling and reaction. We had lessons, we had plans in place. We knew what to do, and we let it slip.

The other situation was stockpile. When I was teaching at the Joint Military Intelligence College [in Washington, D.C.], we went over all this. Pandemic was on our threat list. Many people at the time, myself included, helped to set up the National Strategic Stockpile, which had ventilators, PPE [personal protective equipment] and meds. There were all kinds of equipment to handle outbreaks, and they were strategically placed through major cities in the United States. Every state had several versions of this; the stockpiles were ready for something like this. But they shrank and shrank over the Bush Administration, and then over the Obama Administration, and then over the Trump Administration.

What happened to the stockpiles?

They got used up, and they weren’t replaced. It was a good system, and it was not unmanageable in my opinion. How it ended up shrinking and shrinking and shrinking to the point of only having two sites—one in Maryland and one in California—I can’t explain that.

What countries did better in controlling the coronavirus and why?

Singapore, Japan, Iceland, New Zealand. They waited. You must wait until the virus burden in your community is extremely low. At that moment, that is when you rev up your capability for testing and proper isolation. Anyone who tests positive, regardless of symptoms—and that was another huge mistake we made in the United States, to wait for symptoms of the disease to show up before testing—you isolate anyone who has symptoms. Anyone in close contact [to the person who tested positive]; you quarantine them [even] if they test negative or if you cannot test them. You quarantine close contacts that may turn positive, and you are consistent with that.

What else were some of the steps that could have slowed the virus here in the United States?

Something that was done in many countries that we didn’t do here is, for every positive patient, you test their household members—all of them, from little kids all the way up. Additionally, you must take the virus seriously and convince the public about the importance of doing all the things that everyone’s been talking about for months—respiratory etiquette, physical distancing, masks, hygiene, avoiding crowds. You put these practices in place. Then, when you reopen, you do so while keeping that vigilance to the absolute maximum so that anytime something crops up, you can immediately make a minimal footprint out of it.

What makes COVID-19 so much more deadly than other viruses?

Now you’re getting into interesting host pathogen interactions. This virus has a new way of attaching to the angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE-2) receptor, a protein on the surface of many cell types. How it attaches to the receptor is one that has never been predicted in humans.

You created a program for the U.S. government on the Science and Policy of Bio Warfare and Bio Terrorism. What are your thoughts on the theory that the virus was created in a lab—and accidentally or purposely released?

For one, when we do genetic engineering, there are tools that we use [in the process], and there are residues from using these tools that are not present in this virus. There’s no residue in this virus of having been genetically engineered. There is also a mountain of work that has already demonstrated that this virus recombines frequently in nature and changes up a lot. All evidence suggests that the virus has a natural, animal origin and is not a constructed virus.

Are we entering a new chapter in our history, one where we’re a pandemic nation?

This will pass. The question is how many people will die and how many people will have long-term morbidity from this virus? These things eventually extinguish themselves as changes happen—even natural changes. Bad planning, bad strategy and bad leadership not just here but by so many leaders throughout the world was why this caused so much harm.

I don’t think it’s the virus that will make us a pandemic nation. It’s how we handle it.

Is Florida more susceptible to the virus than other places?

I think any community that doesn’t place science and hard evidence over emotion and devotion to something other than facts is going to be more susceptible.

Some people said that warmer weather would help to alleviate the pandemic. I was one of the few people who said that’s not true. There is good scientific reason to think it would, in the sense that we do know the virus is susceptible to heat and high UV exposure. But the virus also transmits by people being in close contact. And, in hot-weather environments like Florida, people go indoors where the environment is ideal for the virus. We like 74 degrees, which the virus loves, and we like 50 percent humidity, which is ideal for the SARS-2 virus.

Is academia helping to propel the research to assist in taming the virus?

Actually, I have always been the sharing kind, but I’ve never seen so much sharing as I’ve seen during this pandemic nationally and internationally; rival universities are becoming partners, because the need is very clear. So, yes, academic institutions are definitely doing their part to share resources. The sharing of information through medical journals and newspapers is another piece.

Are there ways that we can avoid something like this from happening again?

Let’s remember that Mother Nature is the biggest terrorist of all. And she will hit. It’s unpredictable exactly where or when, so you have to figure out ways to be prepared, like having the National Strategic Stockpile, like doing surveillance and studying nature and the way it works.

One of the things I teach, and the One Health perspective [the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lead One Health efforts in the United States and abroad. One of its priorities is the prevention of zoonotic diseases—diseases spread from animals to humans. Six out of every 10 known infectious diseases in people can be spread from animals, and three out of every four new or emerging infectious diseases in people come from animals, according to the CDC] is to find the outbreak when the outbreak is in animals, before it spills over to humans. Deal with it there.

That takes a lot of vigilance and a lot of interest in our world and a recognition of how things on Earth are interconnected. All disease—and it’s more obvious with some diseases than others and maximally obvious with COVID-19—has a relationship with animals, with the environment, and [with] the social determinants of health and the impact on the economy. It’s really critical to our well-being to recognize that we have to keep the whole thing in balance to the best of our ability in order to live our maximum best life.

How are we going to get the coronavirus under control? Will it be a vaccine?

Part of my problem with the Operation Warp Speed concept is that you still don’t know what’s going to happen in a year until that year has passed with a vaccine. We don’t know how good the immunity is until a year has passed, and you can’t change that no matter how much money you pour into it.

The only reason we need a vaccine is because we can’t behave as humans. If we behaved, we could get rid of the virus without a pharmaceutical. That’s the truth.