It’s been more than a half-century since Paul Rodgers was playing bass in a garage band whose lead singer couldn’t handle Little Richard. The band turned to Rodgers, 14 at the time, and asked him to step up to the microphone and take a crack at “Good Golly, Miss Molly.”

The die had been cast.

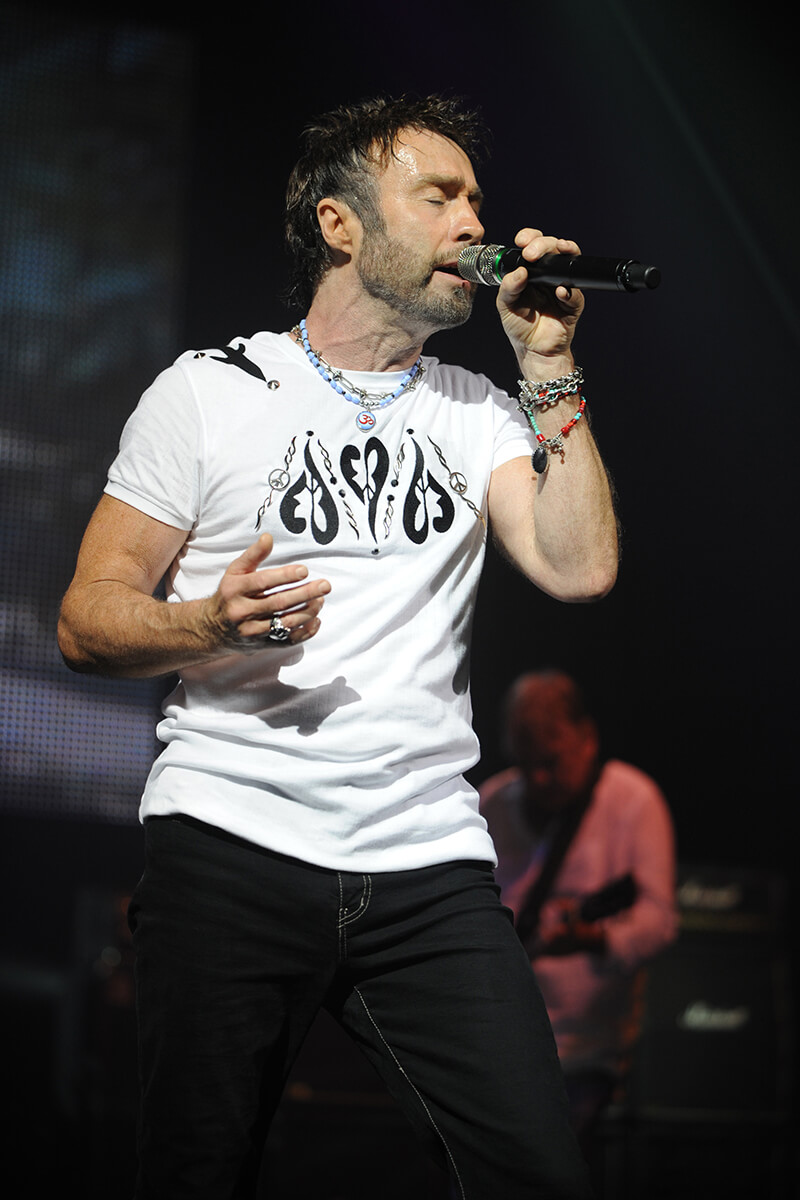

In the 48 years since his band, Free, scored a No. 1 hit with the song, “All Right Now,” Rodgers has enjoyed the kind of career as a front man that most rock musicians can only dream about. During his original incarnation with Bad Company (1973-82), the band released four albums that reached the Billboard top five in the U.S. He then joined forces with Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page in the band, The Firm; later, starting in 2005, he toured for four years with Queen. Along the way, Rodgers released various solo projects and, eventually, returned to play with Bad Company from time to time.

“I’ve reached an age where I realize what a great life I’ve had,” says Rodgers, 68. “I have all this music, and people are still interested. It’s a joy to put a show together from all that material—and have the crowd become part of what we’re doing.”

Rodgers, who takes the stage with Simon Kirke from the original Bad Company lineup this month at Hard Rock Live, reflects on his rock-n-roll journey with Lifestyle.

You’ve paid tribute to the blues and R&B music that influenced you as a youth on a couple of your solo projects. What is it about that music that resonates with you?

Whatever it is, it’s still influencing me. I think of Albert King, I think of B.B. King and his testifying about relationships. The whole thing was so amazing to me coming from the northeast of England, where emotions, really, are kept under wraps. These guys were expressing such deep feelings; it’s such a release. When I first heard that, I thought, “That’s for me.”

When you first broke big with Free in the late 1960s, British rock was at its peak. How did the blues and other influences play into that explosion?

The Rolling Stones were a blues band initially, so what evolved was this blues boom. Out of that came Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix and so much great music. We were being influenced by guys from the States, but it was a different pressure cooker in the UK. So we’d turn around the sound, and that music would go back to the States. The influences were very mixed, and going back and forth across the Atlantic.

Then there were The Beatles; they weren’t really a blues band, but they were so melodic and so creative, so some of that seeped into our work.

You were a teenager when Free released its first album. Were you ready to handle what was coming down the road?

We thought we were all grown up. We weren’t. It’s a heavy-duty business. There were record executives, managers, lawyers—a whole business set up, just waiting for the next big thing. They were ready to sign it, take it, use it, abuse it. And you’re just kids. We were totally a garage band, and we were ready to sign anything. We were so young that we weren’t legally entitled to sign the contract; our parents had to sign in order for it to be binding.

After Free disbanded, we went our different ways. There was a road manager who worked for Free who went to work for Led Zeppelin. He encouraged me to call Peter Grant, who managed Zeppelin. Eventually, I got my courage up and I called Peter. I said that I heard he was interested in managing other acts. He said (in a deep voice), “Well, I’m interested in you.”

I said, “Well, Peter, I come with a band—and we’re going to be called Bad Company.” There was a little to-do about the name; Peter thought it was a little too heavy. But you know what, it kind of worked.

Bad Company’s first three albums all charted in the top five. What made that band stand out amid the crowded rock scene of that time?

It’s interesting, there were so many great bands in that era—Led Zeppelin, Queen, Bad Company. We were all striving to be very different from each other. But, now, we’re all put into that category of classic rock. That’s strange to me because we spent so much time trying to create a unique sound.

One of the things that I strive to do is leave space in the music. It’s not filled with a million notes a second. There’s room for the listener to step inside the music, to enter it spiritually. I like that.

Lifestyle recently spoke to Roger Daltrey, and he talked about being the only sober person in The Who at a certain point. Can you relate, given the initial break up of Bad Company?

There was a point where it was getting insane. I don’t know if I should say, but there were so many drugs around. I just felt, no, I’m going to stop doing that. I wanted to keep my health. I felt very separated from the band at that point. And really, they went their way, and I went mine.

I like to live clean, I really do. I’m not interested in going on stage with a hangover. The thought of that is just devastating. The party is on stage. That’s where it’s happening, and that’s what you save your energy for. … You have to organize things with military precision [during a tour]. In order to be wild and free when you walk on that stage, you can’t spend the rest of your time under a table.

It came out in 2011 that The Doors wanted you to replace Jim Morrison after he died in July 1971. Had you known about it, at the time, what would you have done?

I didn’t even know until many, many years later. I played in the ’80s or ’90s with a later version of The Doors. (Guitarist) Robbie Krieger came up to me and said, “You probably don’t know this, but after Jim died, the rest of the band flew to London and we were looking for you. We were going to ask you to join the band—but we couldn’t find you.”

I was buried in the country, in a little cottage, and I was working with (guitarist) Mick Ralphs on the first Bad Company album; at the time, we were keeping it all under wraps. So, no one knew where I was.

The Doors were fantastic. They were one of those bands that went off into jams that would last 20 minutes; every song was like this musical journey. It was flattering to hear that, but I don’t know what my reaction would have been. Mick and I were very focused on what we were working on at the time. [When I’ve made] career moves, it’s always more of a “feel” thing. You have to follow your heart.

When you and Jimmy Page launch The Firm in 1984, it’s the first major project for both of you since Bad Company and Led Zeppelin. Looking back, do you think that collaboration would have been different had you both put more distance between your past bands?

Maybe. It’s hard to say. After I left Bad Company, I didn’t really want to tour. I had a studio in my house, and I just wanted to make music. Jimmy would pop around and listen to what I was doing. Eventually, as musicians do, we started to jam. And we started to write songs together. And all of the sudden, it was a collaboration.

We got a call from Eric Clapton’s management at the time, and they heard we were in the studio. How they heard, I don’t know. They needed another band for the ARMS (Action into Research for MS) charity tour in the U.S. We told them it was just the two of us, and we only had about 30 minutes of material. They said, “We’ll provide a rhythm section, and you only have to play a half-hour.” So we kind of ran out of excuses.

Jimmy was very keen to get on stage again. I was less keen, I must admit. But I felt we should go for it. And from that, The Firm was born. It’s one of those things, as often happens to me, that evolves out of a connection to someone.

Jimmy Page is one of the greatest guitar players in the world. When Led Zeppelin took on Bad Company (their management handled the band), it was a fantastic boost for us. They were the biggest band in the world, and they gave back by signing young bands. I felt a really strong desire to do something with Jimmy.

How did your collaboration with Queen come about?

We had played a TV show together in the UK; they wanted me to sing “All Right Now,” and Queen was going to play, “We Will Rock You/We Are the Champions.” Brian knew I didn’t have a band for the show, so he suggested that Queen be my band for “All Right Now,” if I would be their singer. It was fantastic. We had an amazing rapport.

He called me afterward and said, “How would you fancy doing a small European tour, just for fun?” Prior to the TV show, my reaction probably would have been: I don’t think we’re close enough [in sound to handle Queen songs]. But having played with Queen, I felt there was a point at which we did connect. At the very least, it was in the ballpark.

So, I said yes. We went into rehearsals, and the next thing I knew four years had passed. We went around the world twice; we made a studio album. At that point, I was ready to step away and do my own thing again.

What was the challenge of tackling songs with Freddie Mercury’s indelible stamp on them?

I tried not to worry about the expectations, otherwise, it would have been overwhelming. I thought a lot about how to handle it. And the only way to do it was to be myself. What does that mean? It means taking the Queen songs and singing them my own way and letting the music speak for itself. That was my guiding principle.

What does it say about the enduring appeal of rock that so many bands of your era continue to successfully tour?

We have a lot of experience with the magic of playing on stage. And it is a magic. There are so many aspects of music—the songwriting, the rehearsing, the recording. And then there’s the stage. You only get a feel for that after doing a lot of touring. You understand that people come from miles around, from different lives, and they come together in this one space. And they become one field of energy. That’s the attraction of any kind of show, really. Comedy. Theater. It’s a coming together. It’s almost primeval, a gathering of the clan around the campfire.

And it’s a beautiful thing. From the soul to the soul. You can’t really fake that. That’s what our music has, I’d like to believe.

Bad Company

When: Feb. 13, 8 p.m.

Where: Hard Rock Live, Seminole Hard Rock Hotel & Casino, Hollywood

Tickets: Starting at $50

Contact: seminolehardrockhollywood.com, ticketmaster.com