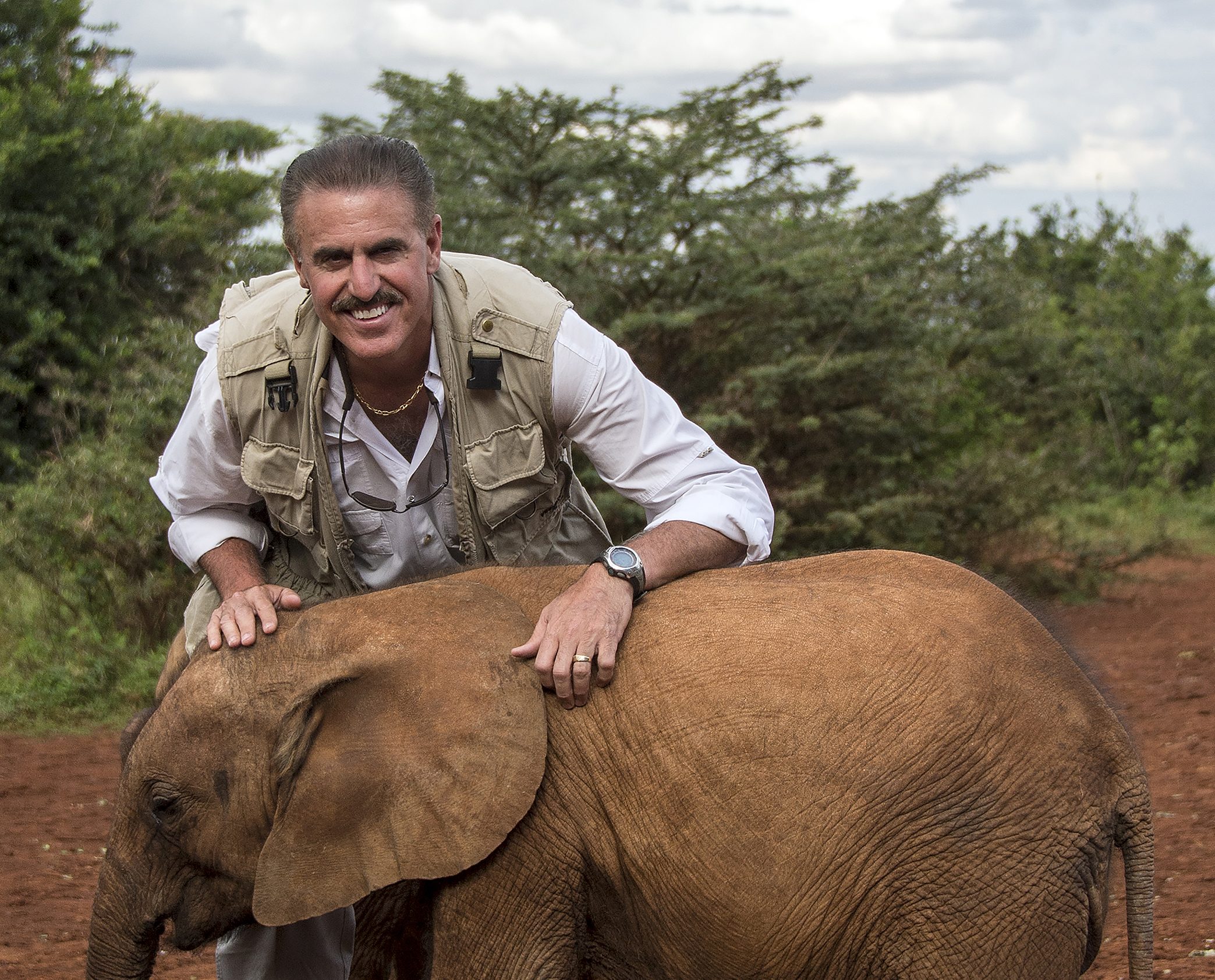

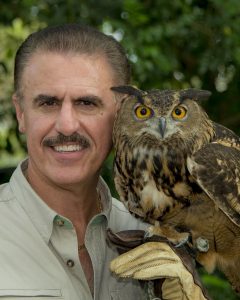

If there’s anyone who can claim that they’re living their best life, it’s Ron Magill, whose job as Zoo Miami’s goodwill ambassador and communications director has taken him around the world.

“I’ve put radio collars on lions in the Serengeti. I’ve tracked tigers … in India. I’ve tracked polar bears in the Arctic. I’ve gone swimming with killer whales in the Galápagos,” Magill says. “[When] I look back on it, I cannot believe I’ve been able to do these things. So I’m really living the dream.”

This year marks Magill’s 40th year at the zoo, the longevity of his career a sign that he never gets bored because, as he puts it “no day is exactly the same.” He’s shown off animals on national TV, made nature documentaries, entertained audiences with appearances on the variety show “Sabado Gigante,” become a wildlife photographer—and even helped Disney animators capture animal movement during the production of “The Lion King.” Before he started at the zoo, he was a curator at the Miami Serpentarium (the popular attraction on South Dixie Highway that closed in 1984) and an animal handler on the set of “Miami Vice,” a job he held concurrently with his zoo job in the early ’80s.

Magill’s current projects reflect how his love for animals started—watching “Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom” every Sunday night and visiting the Bronx Zoo with his family while growing up in New York City. Today, he has his own nature show, “Mundo Salvaje con Ron Magill,” which premiered last year on Hispanic network HITN. And he furthers his belief that today’s zoos must be “vectors of conservation” through the zoo’s Ron Magill Conservation Endowment, which supports conservation projects around the world. It provides for such things as an SUV for cheetah research in Kenya and a new motor for a boat for Audubon Florida to research the Everglades.

We asked the Miami Palmetto Senior High graduate, 59, more about his career and his favorite animal.

1. What do you remember about your trips to the Bronx Zoo?

1. What do you remember about your trips to the Bronx Zoo?

“I certainly remember that connection that occurred when I looked at an animal, whether it be a tiger or a bison or a bird—eye-to-eye [with] a large exotic animal … . It was something that made me know that I always wanted to be able to work with and for these animals. … You can say all you want about reading a book, watching a documentary, looking at a photograph. But there’s something that looking at an animal eye-to-eye in person does. And that’s the importance of the zoo. It offers these great windows where kids especially can connect with animals, because that’s what happened to me at the Bronx Zoo.”

2. Have you ever felt a personal connection to an animal?

“There are certainly animals that I have connected with in the sense that I feel that they like me. And I know that only because I see how they dislike others. But I need to be always very careful, because that’s where you get sucked into a trap and that’s when you get hurt. … Having said that, there are animals that I do have a connection with.

“I had a connection with the first tigress at the zoo named Natasha. One of the most emotional moments I’ve had working at the zoo is when Natasha had the first tigers ever born at the zoo. … She had her cubs back in a den, and I sat outside the area where there was an enclosure in front of the den. She saw me getting there. She chuffed at me. She went back into the den. She carried one of her cubs out in her mouth and brought it to me and laid it down right in front of me and just lay down there as if to show me her cubs. It’s one of those things that you just never, ever forget.”

3. What are some South Florida wildlife issues people should pay attention to?

“The Everglades is such an incredible treasure that so many of us take for granted because it’s in our backyard. I tell people all the time, ‘People travel from around the world to come see this treasure.’ … It’s the source of so many things that are a reflection of the quality of life of South Florida. We’ve got a lot of challenges facing us, whether it be climate change that’s leading to sea-level rise, or saltwater intrusion that can affect fresh water availability.

“We have real problems with invasive species. … People have heard about things like the pythons and the lion fish that could be tremendous detriments to our environment. But they don’t hear a lot about some of the invasive plants and invasive insects that economically could be catastrophic to South Florida, whether it be removing agricultural crops or causing infestations.”

4. What sets your show apart from other wildlife shows?

“One of the things that I get a little disappointed in when I see today’s programming is sensationalizing animals, and trying to put that fear factor into [audiences]. I’m seeing a lot of shows like ‘When Animals Attack!’ or ‘World’s Deadliest’ or ‘River Monsters’—these are all shows portraying animals as something that’s going to kill you. It’s the wrong message. … [My show] is different from other shows in that it shows this incredible footage of wildlife done by some of the best cinematographers in the world. I introduce it and describe what’s going on in a way that gets people fascinated about it. It’s not going to make you be afraid of it. It’s going to make you want to learn more about it.”

5. What’s your favorite animal?

“An animal called the harpy eagle. [When] I was a little kid, I never saw one alive. The only one I ever saw was a stuffed one at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Fast forward in my life, I marry this woman of Panamanian descent, so I go to Panama to visit family, and I hear they have a small zoo there that has live harpy eagles. It was one of the most bittersweet moments; it was sweet because I got to see my first harpy eagles alive and it was amazing. It was bitter because they were in the most horrific cage I’ve ever seen in my life. To make a long story short, I met with the mayor of Panama City who was in charge of the budget for that place. I was able to get sponsorships from American Airlines and Visa and Sony Corporation, and I built a million-dollar center for the harpy eagle in Panama, the largest harpy eagle center in the world [which opened in 1998]. And, more important, I was able to become part of a grassroots effort where we presented to the Panamanian congress on April 10, 2002; and on that date the congress passed a law officially designating the harpy eagle the national bird of Panama. … It is one of the things I’m most proud of in that we started a conservation movement that became part of the fabric of a culture.”