By Kevin Kaminski

The Starbucks near his west Broward County home is empty, save for a few employees doing their final cleanup before closing. After an hourlong conversation, and three cups of oatmeal with trail mix, Tyrone Spong wants to say a few words about the tragedy he initially declined to discuss.

His friend, Jordan Parsons, would die the following afternoon at age 25. The two men chased their respective dreams at JACO Hybrid Training Center in Boca Raton as part of the famed Blackzilians mixed martial arts team. Parsons was a rising MMA star in the featherweight division; Spong is a seminal figure in the sport of kickboxing, a 10-time world champion who, at age 30, has set his sights on the most prestigious combat title of all: the heavyweight boxing championship.

In this moment, Spong’s thoughts are not on what might be, but on what could have been. Parsons, the victim of a hit-and-run accident in Delray Beach that made national headlines, will soon be taken off life support. Earlier in the day, Spong and several other MMA fighters bid a final farewell to their friend at Delray Medical Center. It’s a reminder, says the father of four, that every day above ground is a blessing.

“One moment you have everything, the next you have nothing. Or worse: You’re gone,” Spong says. “We think we own the world, but we don’t. We live by the mercy and the grace of nature. People like to act like they’re this or that. But I try to be humble. I’m not better than anyone … until I step in the ring.”

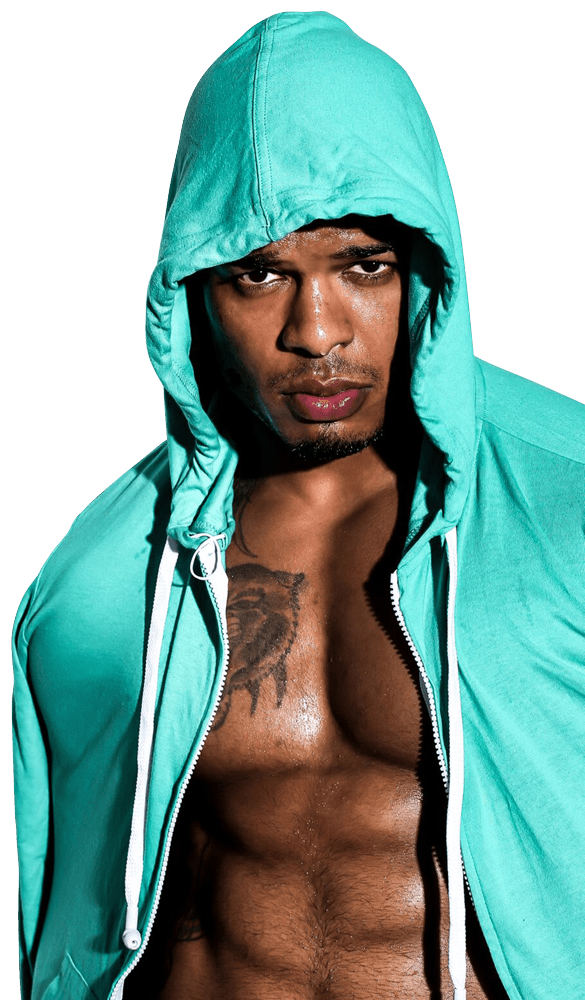

At nearly 6 feet 3 inches and roughly 225 pounds, the heavily tattooed native of Suriname looks every bit as imposing as his kickboxing résumé would suggest—more than 80 knockout victories alone, by Spong’s count. “When I connect,” he says matter-of-factly, “it’s over.” But there’s more to the man who dismantled one of his 2013 opponents in only 16 seconds than meets the eye.

In many ways, it starts with the rich tapestry of Amazon rainforest-inspired animals, artifacts and flora painted on Spong’s body, tattoos that speak to the beloved South American country in which he was born and briefly raised, until his mother moved him to Amsterdam when he was 6. His father, a high-ranking police officer at the time, would stay behind—for good.

“It was tough on my mom being a single parent and tough on me,” Spong says. “I’m a nature person; I love to be outdoors. To be ripped away from the jungle, to leave that freedom for a third-story apartment in the toughest neighborhood in Amsterdam? I felt trapped. At that age, I didn’t understand.”

Spong knew enough to stand up for himself when older kids picked on him for being quiet—or when they discovered his fondness for birds, of which there are more than 700 species in Suriname. “You always had to prove yourself,” he says. “I got into a lot of street fights in Amsterdam. I couldn’t accept being bullied.”

After losing interest in the disciplines as a child, Spong became obsessed with karate and taekwondo at age 13, never missing a practice. Two years later, he won his first amateur kickboxing fight by knockout. He would turn professional at 18 and capture his first world championship shortly thereafter.

Fighting mostly in the Netherlands, Spong wouldn’t visit the U.S. until he was in his early 20s. Once there, he trained briefly in Las Vegas with Floyd Mayweather Sr. According to Spong, so impressed was the father of Floyd “Money” Mayweather Jr. with the martial artist’s potential as a boxer that he and promoter Bob Arum offered the kickboxer a contract.“I was so young and so on top of my game as a kickboxer that I was scared to leave my trusted environment,” Spong says. “It wasn’t my time.”

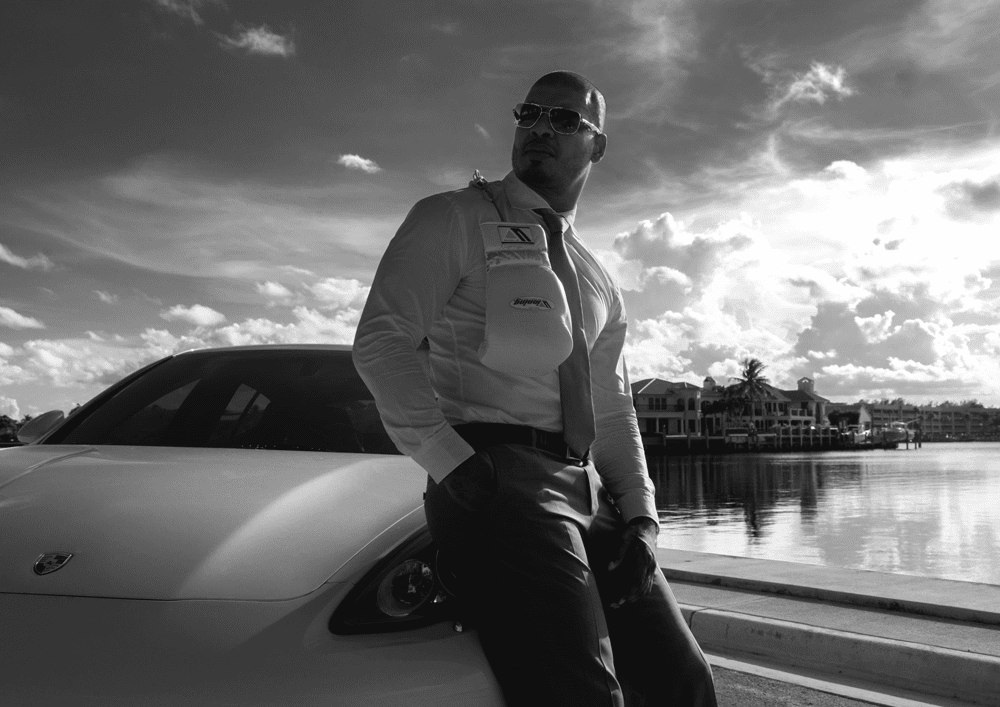

Spong eventually moved to South Florida to help Boca-based MMA fighter Rashad Evans, one of the signature Blackzilians, train for his 2011 light-heavyweight fight with Tito Ortiz. Though he continued to win world titles in kickboxing, there were few challenges left for Spong, who could see the sport losing its luster compared to MMA (which he tried and won two fights) and boxing.

In 2014, during the first round of a kickboxing battle in Istanbul against Gökhan Saki, Spong fractured his tibia and fibula. Ten months later, on the same day (March 6) that Mike Tyson made his professional debut in 1985, Spong stepped into the boxing ring for the first time, disposing of a Hungarian fighter named Gabor Farkas in a little over a minute. Since then, he has reeled off three more victories, all by knockout.

When asked why he believes his martial arts skills will translate to the boxing ring, Spong puts down his oatmeal spoon and inches forward in his chair. “I’ve been kicked in the body by guys who weigh 270 pounds; I’ve been kneed in the jaw by guys who weigh 280 pounds,” he says. “I’m not saying I’m Superman, but there aren’t a lot of guys who are better warriors than me. That doesn’t always guarantee a win. But the toughness? The heart? The mental strength? The balls? It’s all there.”

Nearly 10 years after being courted by Mayweather Sr., Spong believes his time as a boxer finally has arrived. He’s not trying to win the heavyweight championship belt, he’ll tell you; he will win it.

“Had I become a boxer in my early 20s, I’d be the biggest star in the sport,” he says. “I would have done the same thing that I did in kickboxing. I would have been a multiple champion in different weight classes. But I can still show that I’m a champion—and one of the best combat sports athletes, period. That’s my goal.”