Just because you have hands, Adam Duritz suggests, doesn’t mean you can paint. It was the same, the lead singer of Counting Crows notes, with his voice in the years before his alternative rock band exploded on the music scene in the early 1990s.

He had one. And it was good.

“But I didn’t know how to do anything with my voice,” the 58-year-old Duritz says. “Learning to be a great singer is a different thing.”

He points to a session with David Immerglück before they were in the Crows together. The versatile multi-instrumentalist asked Duritz to sing lead on the hard-rock album of another musician. “[Immerglück] pushed me to sing in all these ways I’d never sung before. It was difficult, and I was frustrated,” Duritz says. “But he pushed me so hard that I learned about myself, about singing, and about how to express things that I’d never experienced before. There was so much more I could do with my voice than just sound nice.

“I could make people feel things.”

Thirty years after the release of August and Everything After, the Bay area band’s debut album that sold more than 7 million copies in the United States, Duritz’s now-iconic voice (not to mention his personal, introspective lyrics) continues to resonate with fans of Counting Crows. The group that’s scored hits with “Mr. Jones” and “Rain King” (Duritz says the challenging vocals on those two songs off August both required about 60 takes), as well as “A Long December” (off its chart-topping sophomore effect, Recovering the Satellites), is on the road this summer with Dashboard Confessional—including a stop at Hard Rock Live in early August.

In a wide-ranging interview with Lifestyle, the engaging front man touched on the band’s journey, how the pandemic changed his relationship with the audience, and why music isn’t a panacea for the mental illness he’s been so candid about through the years.

Rock bands with core members who’ve been together two, three decades are few and far between. To what do you attribute that sustained connection?

Bands break up for a lot of reasons, but one of them is that there’s always good logic to justify why you—whoever “you” are—deserve more. Early on, I figured out that it doesn’t matter if one person deserves more if there’s not enough for everyone else in the group. What was making me happy, what was giving me artistic satisfaction, was being in this band. So, that was my priority. I wanted to keep the band together.

You don’t dream about having a career that has a big hit and then flops after a couple of years. You dream about playing for the rest of your life. We’re still managing to do that. And I definitely appreciate the rarity of it.

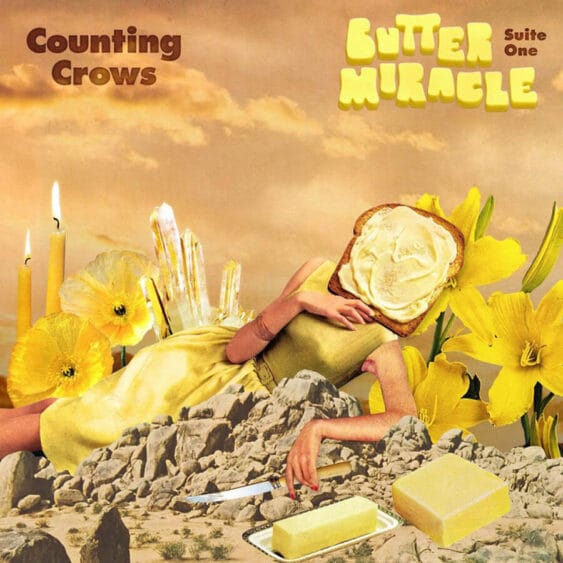

The band also continues to push the envelope. Butter Miracle (released in 2021) is a seamless suite of four songs [the Crows play the entire 19-minute suite in concert]. Are you proud of how it turned out?

I really am—in part, because it was so challenging to write. It was composed to work as one long piece, but you don’t record it as one 20-minute session. You’re doing it as individual songs. What we’d do is, at the end of each song, we’d keep playing into the next song—and then stop a few lines into it. Theoretically, that should work [when it comes to producing the album]. But you don’t know if the sonics of one song will work next to the sonics of another. It wasn’t until the very end—after we mixed every song—that we put it all together. Until that moment, you don’t know if it’s going to work. When it did, it was so satisfying.

I like that we’re not trying to go back and make the sequel to August and Everything After. We’re still chasing art, chasing things that fascinate us.

Do you recall anything about the making of August and Everything After that led you to believe it would connect the way that it did?

I don’t think any of us knows what makes something resonate with listeners. And you can’t really chase that. The mistake artists make is thinking too much about creating music that’s popular. Just make great records that resonate with you—and let the chips fall where they may as far as people liking it. I know records that, to me, are some of the best ever made—and nobody has heard them. And there are records that are terrible that everybody loves.

I did think August was a great record. I also thought Recovering the Satellites was a great record. Sometimes, whatever the zeitgeist of the moment is, the world resonates with you. None of us thought August would be as huge as it was—including the record company. But at that moment, it’s what everybody wanted to listen to.

It’s interesting, speaking to zeitgeist, how the stars can align for an album and a band. What are the challenges, though, when you’re shot out of a cannon like that?

The scary part of that kind of [debut album] is that it’s often [followed] by a backlash. If you’re not careful, that can be the end of your career. You can spend too much time trying to milk it—and find that no one ever wants to hear anything from you again. Even as careful as we were, we still faced a lot of that. We had to weather that backlash.

How many bands have big first albums but don’t survive that second album? We worked really hard to make an entirely different record with Recovering the Satellites. We kept chasing our passions and didn’t make August and Everything After again and again. Looking back, that probably saved our career.

Bono and The Edge have been revisiting early U2 songs with modern-day perspective. Do you view the songs on August through a different prism 30 years later?

Yes, but I viewed them through a different prism three weeks later, too [Duritz chuckles].

I was talking to someone recently who said we should re-record all our records, like Taylor Swift did, so that they’re your versions and not the record label’s version.

All I could think of was that I have no idea how the record-label versions go anymore! I’ve been singing them differently since the first gig. I’ve always felt that’s what keeps songs fresh—and what keeps concerts fresh.

Your life [as a musician] is like a coffee filter. And you pour your songs through it that day. So, every day is a chance to reimagine your songs.

Believe me, “Mr. Jones” became a different song for me once I lived the things that the song was imagining when I wrote it.

You’ve been candid about your depersonalization condition (a type of dissociative disorder in which people feel like they’re living in a dream; they’ll observe themselves from outside their body or believe things around them aren’t real). Has that candor had an impact on people who also live with the disorder?

I don’t really know what the impact has been. Some people have talked to me about it. I do think that one of the hardest parts about mental illness—or anything that makes you feel different from everyone else—is that you feel completely alone in it. So, when you recognize there’s someone out there who understands, someone just like you, I imagine that probably helps.

For me, it was something I didn’t want to talk about when I felt like I was going down a hole. I didn’t want to talk about it when I was in danger of losing it. But I finally felt OK talking about it, in part because it was such a big aspect of my music—and something people weren’t aware of.

It was almost selfish when I started talking about it because it illuminated a lot of things. At that point, I wasn’t better. You don’t necessarily get better. But I wasn’t falling apart anymore.

How important has your music been in working through the issues involved with the disorder?

None. It doesn’t do that. It’s not cathartic. And it doesn’t fix anything.

The weird thing about mental illness is that it’s less like a disease and more like a handicap. There’s no cure, a lot of the time. You’re not necessarily going to get better. But you can learn to live with it, you can learn that it’s not going to overwhelm or crush you.

The thing about the songs isn’t that they fix the mental illness, but they’re what I can do while being someone who suffers from mental illness. And it enables me to have a meaningful, productive life. At one point, that didn’t seem like it would be possible. I felt like I wasn’t able to cope with things the way that other people do—and so I wasn’t going to be able to function. But then I found a way to function.

I’m able to have a career where I’m in charge. I don’t have a boss. I don’t have to feel exposed and vulnerable with my mental illness because I’m free to stay home. I can survive two years of a pandemic. That’s not as easy for a lot of other people.

You’re approaching age 60. Where are you at in life right now, and how does that impact your music?

The pandemic had a definite effect on me. Our career was supposed to be about a two-year thing. Instead, it’s been a 30-year thing. It doesn’t really work that way very often for bands. And I don’t know that I had given that much thought. When I’m on stage, I get lost. I do what I do, and I’m just in the music.

But I did notice, after we began performing again, that I felt so appreciative of the audience. As much as I’ve always appreciated the effort that we’ve made to keep our career going, none of that matters if no one comes to hear you play. During the pandemic, I really did wonder if anyone was going to come back. After two years off, maybe they don’t go to concerts anymore. And if you are going to get rid of a band [to support], it’s not going to be Taylor Swift. It’s going to be a band not at the center of culture. Like us.

When everyone showed up, I found myself getting choked up on stage for the first time in my career. It’s not that I took the audience for granted. But, now, I do think about how much I appreciate the people who keep coming back after all these years.

It’s a weird thing. I also find myself wanting to work more these days. I want to be on tour. I want to play.

When you want to be an artist with your career, it’s a little scary. You don’t know how you’re going to support yourself. You feel like a bum. So, when I got this job finally, I became a workaholic. And all I’ve done is work since then. But when we had two years off, some of those fears came back out of the woodwork. Things from my youth—like not knowing how I was going to take care of myself. I washed dishes and did landscaping and construction work. That wasn’t what I wanted to do, but I didn’t know how to take care of myself doing exactly what I wanted to do. So, there were a lot of fears and insecurities about that in my 20s.

Not being able to work for two years brought a lot of that stuff back. So, that’s part of it too. I appreciate going to work—just because it’s work. Satisfying work.

Counting Crows at Hard Rock Live

When: Aug. 5, 8 p.m.

Where: Seminole Hard Rock Hotel & Casino (1 Seminole Way, Hollywood)

What: According to Adam Duritz, he and his longtime friend and collaborator Chris Carrabba from Dashboard Confessional have wanted to headline a tour—but promoters often balked at the idea of their two soulful bands on the same bill. In the category of better late than never, Counting Crows and Dashboard are on the road together all summer, including this South Florida stop as part of their Banshee Season Tour. Carrabba, who graduated from Boca Raton High School, has Dashboard soaring after a near-fatal motorcycle accident in 2020. Duritz, meanwhile, continues to drive Counting Crows artistically 30 years after the release of the band’s brilliant debut album, August and Everything After.

Did you know: Duritz says that he first met Carrabba doing the Bridge School Benefit, the one-time charity event hosted by Neil Young.

Tickets: myhrl.com