Story by John Pacenti

Steven Kovacs was no more than 5 years old, walking the beaches of Nova Scotia in his native Canada when he found a starfish and “went crazy over this creature.”

“I was just enamored with underwater life from a very young age,” Kovacs recalls. “It was probably watching TV shows such as Jacques Cousteau.”

What began as a childhood interest is now the life aquatic for the Palm Beach County resident, who travels the globe photographing mysterious sea species in all their underwater splendor. Some of his most compelling images, however, are taken in his home waters off Palm Beach County.

Kovacs, 54, specializes in blackwater photography where he dives at night to capture creatures, often in their larval form, right off our coast, creating almost 3D images with the deep abyss as his canvas.

“Blackwater diving is basically going out at night into very deep water and jumping in and seeing what comes up from the depths or floats or swims by,” says Kovacs, who’s a dentist.

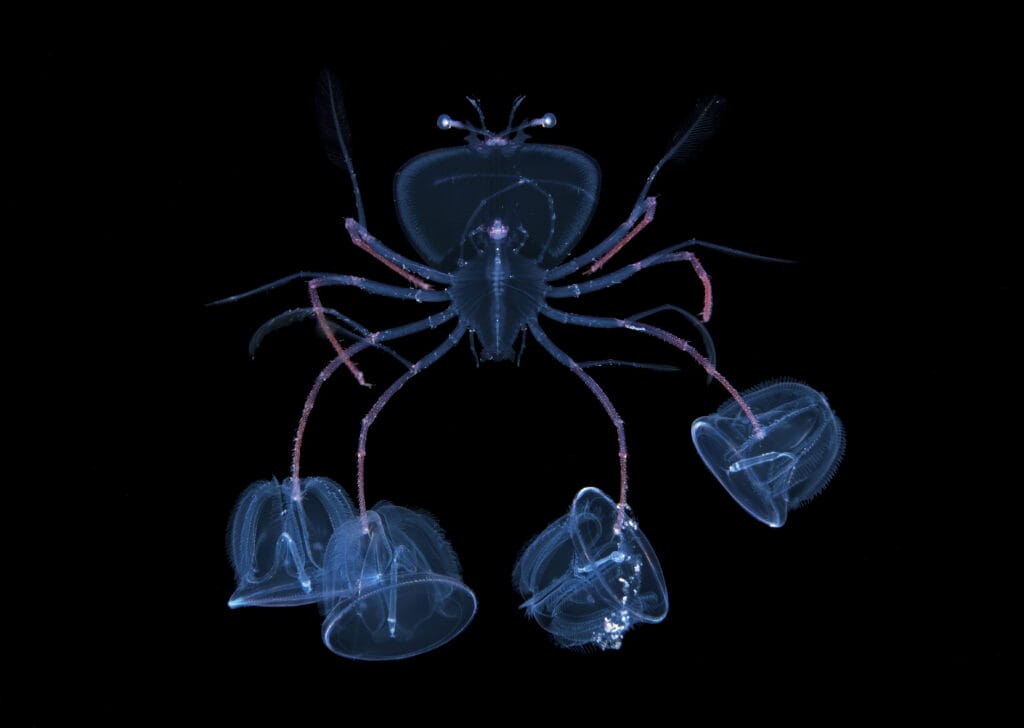

Animals that live deeper during the day migrate toward the surface at night to feed in more nutrient-rich waters, Kovacs says. These include pelagic (open ocean) larval stages of many animals like deepwater fish that would otherwise never be seen.

The diving itself is done at recreational scuba diving limits of no more than 130 feet, but the bottom can be thousands of feet below, depending on the location of the blackwater dive.

In Kona, Hawaii, where Kovacs has recently done photo shoots, the bottom can be 6,000 feet or deeper. Florida depths tend to be in the 700-foot range. For comparison, the Golden Gate Bridge is 745 feet high.

Lights are dropped on a tether, attracting animals at various depths. Kovacs’ camera apparatus looks like a creature itself, with powerful strobes that must recycle once they flash.

The results are striking.

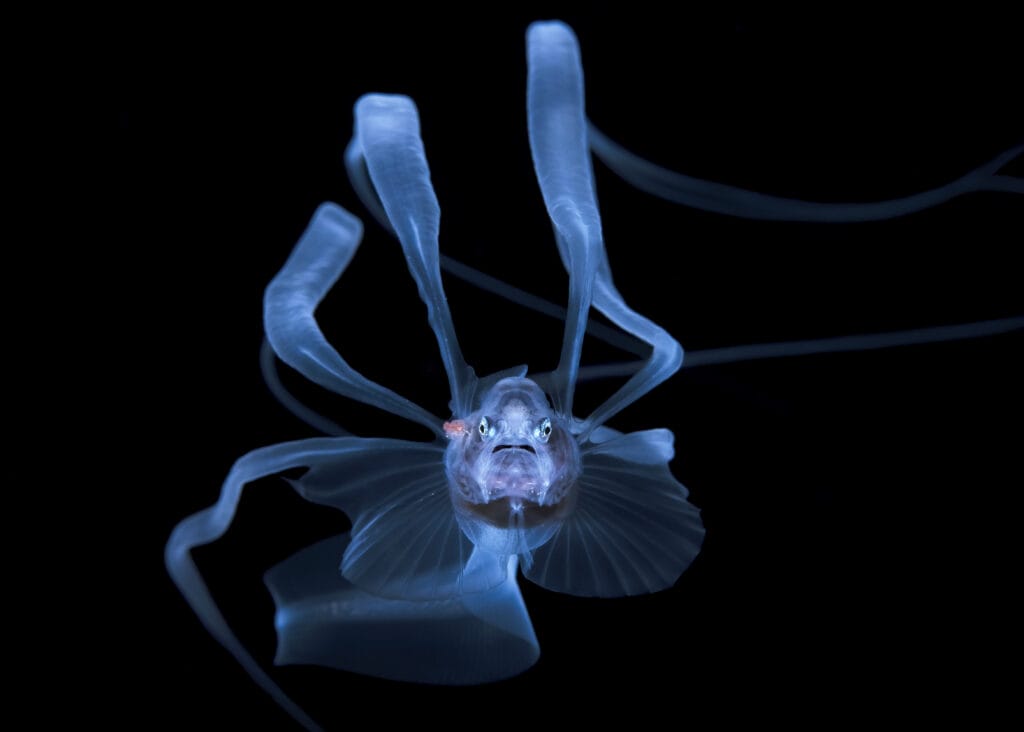

A photo of a ribbonfish is near angelic as its fins float like wings around the specimen, though its reddish, pouty lips give a “Girl With A Pearl Earring” vibe. It is transformed in the light of Kovacs’ camera into something heavenly.

Kovacs’ photo of a diamond squid could be a creature from a blockbuster sci-fi alien flick. With its poised tentacles, it hovers in the dark as if ready to grab the viewer in resplendent red, blue and gold.

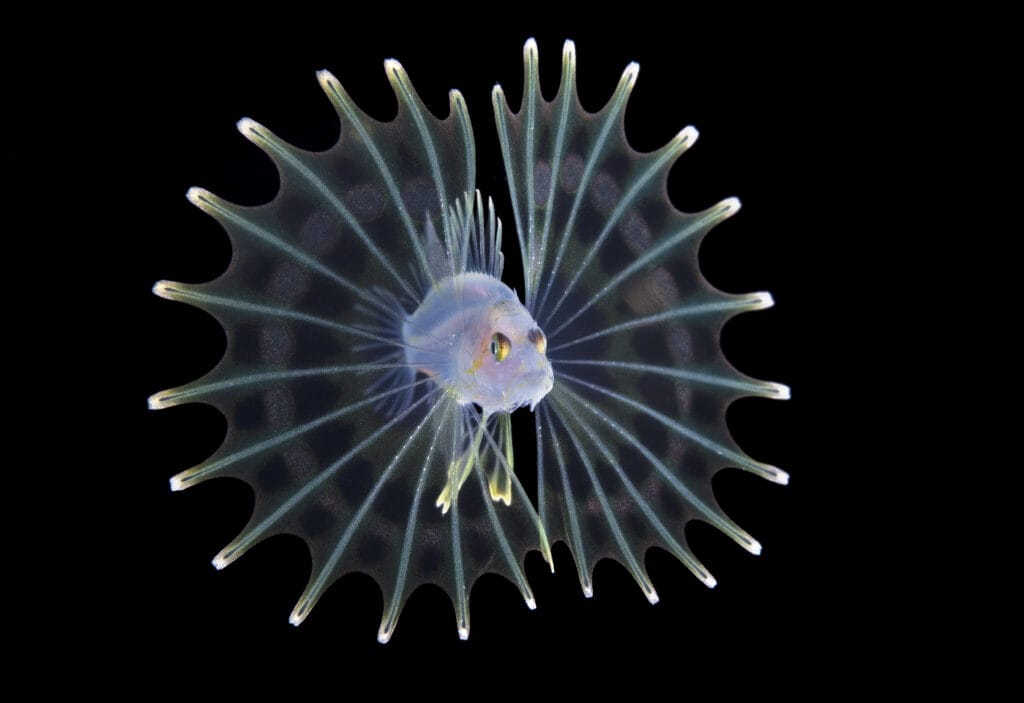

A young lionfish—an invasive species having an impact on South Florida’s reef systems—is rendered in white with gold eyes. It appears startled as it fins fan around its torso.

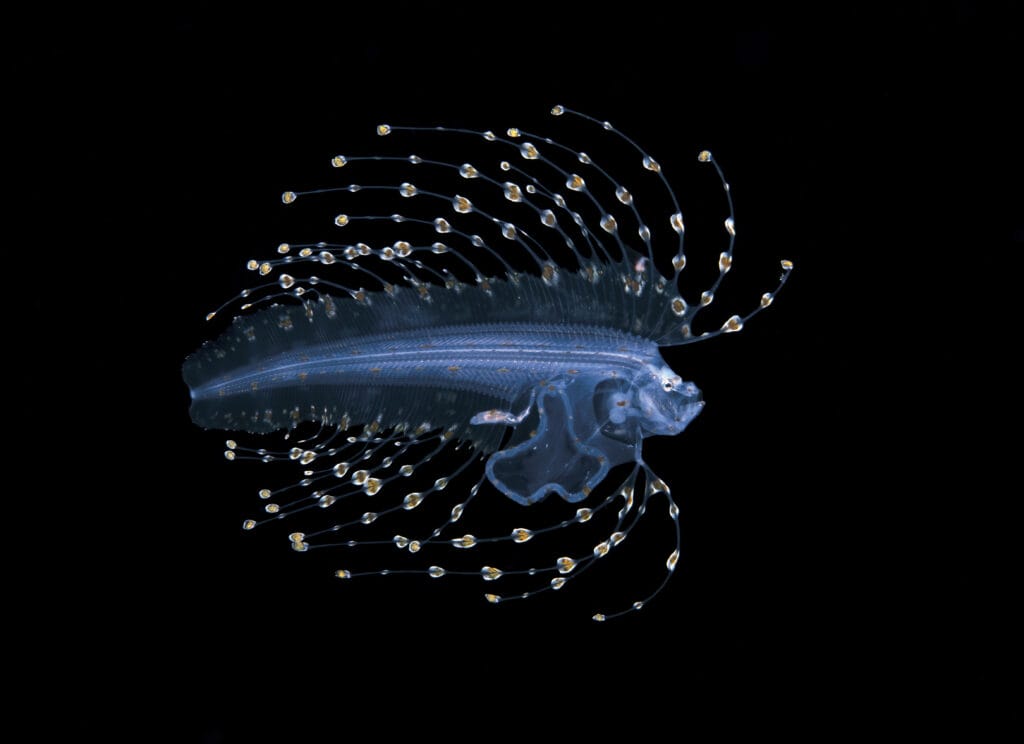

Kovacs’ camera lens has caught elusive creatures such as the cascading blanket octopus, the bejeweled cusk-eel and Acanthonus armatus—aka, the bony-eared assfish, a deep-water cusk-eel species with a grumpy mug that unfurls its fins like flags.

“Acanthonus armatus, is always a highlight,” Kovacs says. “I’ve only seen two larger larvae in 10 years of blackwater diving. To me, it is one of the most stunningly beautiful fish in the sea when it’s in its larval form.”

Beauty isn’t the only element evident in Kovacs’ work. The eeriness of the backdrop leaves viewers to wonder: What’s lurking amid the blackness? As Kovacs knows all too well, there are inherent dangers involved with clicking a shutter deep underwater in the dead of night and miles out to sea.

Sharks, he says, usually mind their own business. However, “swordfish have a nastier reputation for a bad temperament; encountering them is more tense.”

The real photographic challenge, Kovacs admits, is having the patience to dive into the darkness and search for the tiniest sea creatures—with no guarantees.

“You can’t go back the next day and just find a fish in the same place,” Kovacs says. “Encounters are a one-time occurrence—and way too often it may take years of searching before the desired animal is finally found.”