It was the era of La Belle Époque in late 19th century Paris, a “Beautiful Age” of more than just peace, prosperity and technological advances. The cultural scene had exploded, giving artists, authors, poets, actors, singers and dancers an inspired, vibrant atmosphere in which to showcase their talent.

But it took more than just a stage for creatives of the time to gain renown.

As art historian Bonnie Clearwater notes, there could be more than 350 performances at concert halls, theaters and cafés on any given night in Paris during the 1890s.

“How do you break through the noise and become the star that everyone wants to see?” asks the director and chief curator of Nova Southeastern University’s Art Museum Fort Lauderdale. “How does a new performer get recognized?”

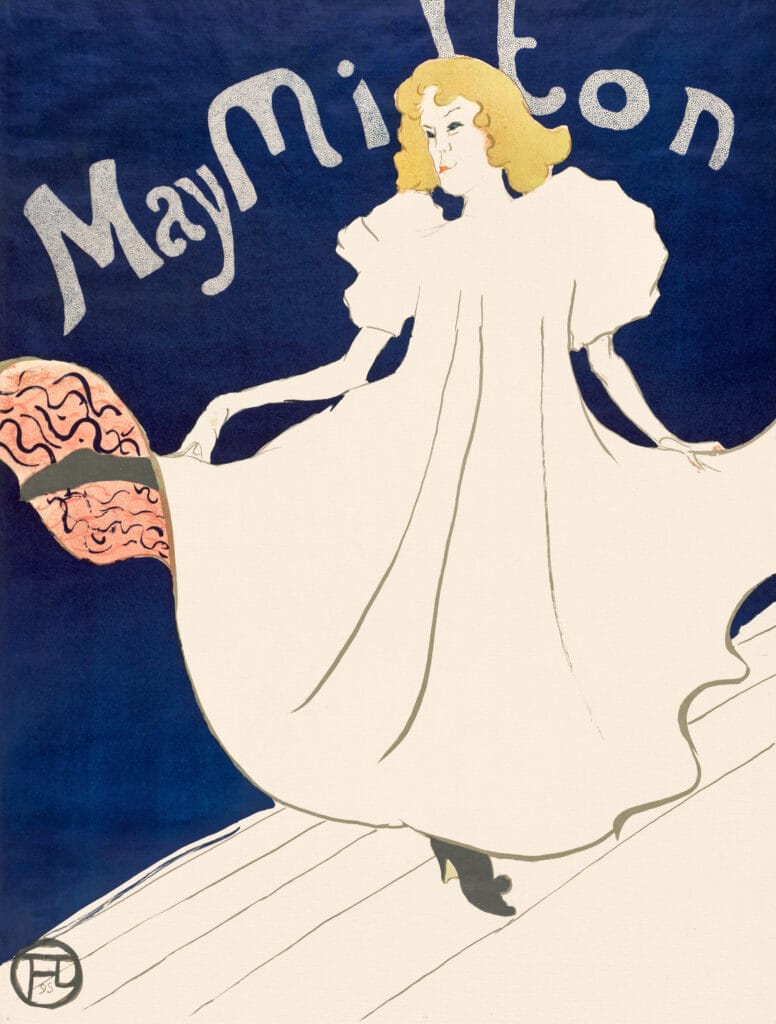

The answer, in this case, involved Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, the post-Impressionist French artist whose promotional posters of performers and the cabaret scene—including the famed Moulin Rouge—adorned the city’s walls and captivated passersby. However, the idea of attracting attention and generating buzz raised larger questions for Clearwater.

“It occurred to me how much Lautrec, with his posters, really created the methods that we use to this day regarding how to market celebrity,” Clearwater says. “I began thinking about how fame is formed, why people crave it, how they use it and how social media has changed the way it’s created.”

Clearwater’s musings on the subject paved the way for “Picturing Fame,” the fascinating exhibition that’s producing its own buzz at NSU Art Museum (nsuartmuseum.org).

The thread of stardom and renown runs through four concurrent exhibitions that comprise the show, but each forum explores different avenues of the umbrella theme.

- Toulouse-Lautrec and the Follies of Fame: Through his drawings, etchings and flamboyant, caricature-style posters, museum guests can see the creative foundation for today’s celebrity-driven marketing strategies.

“Lautrec had a way of capturing the personality and spirit of the celebrity,” Clearwater says. “But he also captured this intriguing connection between the bohemians and the aristocrats who came to their performances—and how each was getting what they wanted from each other.”

- Hooray for Hollywood: Drawn primarily from the museum’s collection, pieces like a Frida Kahlo self-portrait and Catherine Opie’s photo series of Elizabeth Taylor’s intimate possessions touch on our fascination with celebrity and notions of desire, voyeurism and obsession.

“This exhibition looks at the traditional Hollywood star-making machine. How was a Marilyn Monroe created? An Elizabeth Taylor?” Clearwater says. “Andy Warhol recognized that there was no difference between how Hollywood created this celebrity and how a politician used the same methods to create a cult of personality. So, in the exhibition, we have both Warhol’s [1973] print series of Chairman Mao [the founder of the People’s Republic of China, named by Life magazine at the time as the most famous man in the world].”

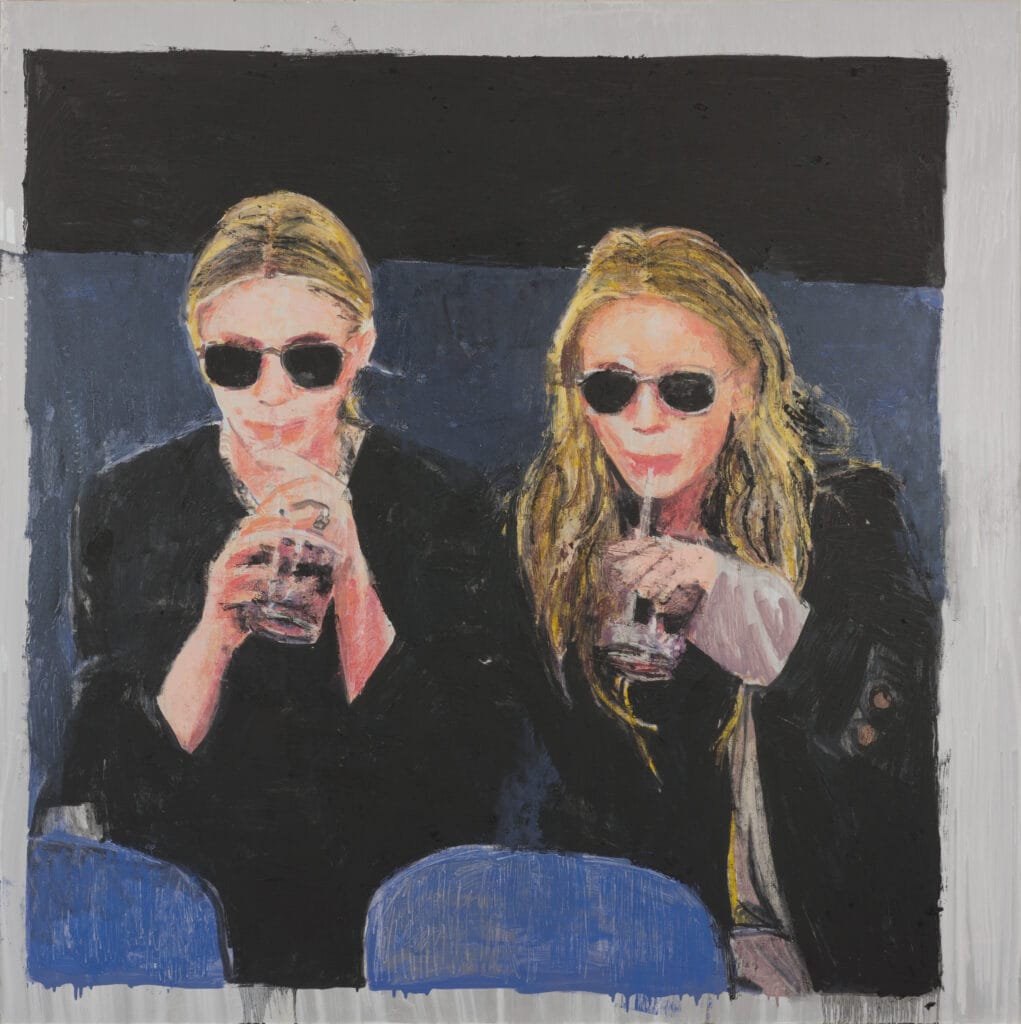

- The Swans—Karen Kilimnik and Stephanie Seymour Paintings and Dresses: The romantic paintings of mid-career artist Kilimnik, paired with selections of vintage haute couture from the collection of supermodel Seymour, serve to reimagine the golden age glamour of turn-of-the-century Paris. “The Swans” speaks to writer Truman Capote’s description of high-society women in the mid-20th-century.

“It represents the type of woman who was famous, basically, for being famous,” Clearwater says. “Capote was fascinated by celebrity—but also by women who were desired by men and admired by the general public in a way that tapped into our aspirational dreams. Fashion was so much a part of creating that image—and that fashion, in turn, contributed to the fame of designers like Yves Saint-Laurent and Christian Dior.”

- Van Gogh, Lautrec and Me by Emilio Martinez: Clearwater is especially excited to showcase the work of Martinez, the Miami artist whose artistic journey she’s followed—and whose collage work involving Van Gogh the museum ultimately purchased.

“He was born in Honduras and came to South Florida when he was about 12,” Clearwater says. “So much of his childhood was indebted to his imagination. His grandparents would tell him about monsters in the woods, and those monsters have stayed real to him in his mind.”

And in his work. Martinez’s deep connection to Van Gogh—inspired by the 2018 Julian Schnabel film about the artist, At Eternity’s Gate—led him to cut up reproductions of Van Gogh’s art and re-contextualize the pieces as monsters in the collage series that NSU bought. In addition, this exhibition features a series of multimedia paintings and collages connected to Lautrec.

“[Martinez] learned that Van Gogh and Lautrec were friends; they met in art school,” Clearwater says. “That led Emilio into exploring Lautrec more deeply. He felt a relationship to his own life—particularly that Lautrec felt he never lived up to his father’s expectations. [That resonated with] Emilio; his parents divorced when he was young, and he felt somehow that he was the reason. The monsters were a way of Emilio getting out his own inner demons, his own feelings about his relationships with people.”

“Picturing Fame” runs through Sept. 3 at NSU Art Museum (1 E. Las Olas Blvd., Fort Lauderdale).