Like an epic novel, the visual stories of Rolando Chang Barrero traverse time and back again. They require heroes ready to confront the toughest of challenges across the generations.

In his last year at Southwest Miami Senior High School, in 1990, he created graphic T-shirts to raise awareness about heroin addiction, urban wear that would be just as relevant today amid the opioids flooding towns and cities. At the height of the 1990s AIDS crisis, the multimedia and performance artist designed banners and props for New York City marches with ACT UP. He’s resurrecting his fashion shows to protest U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement policies.

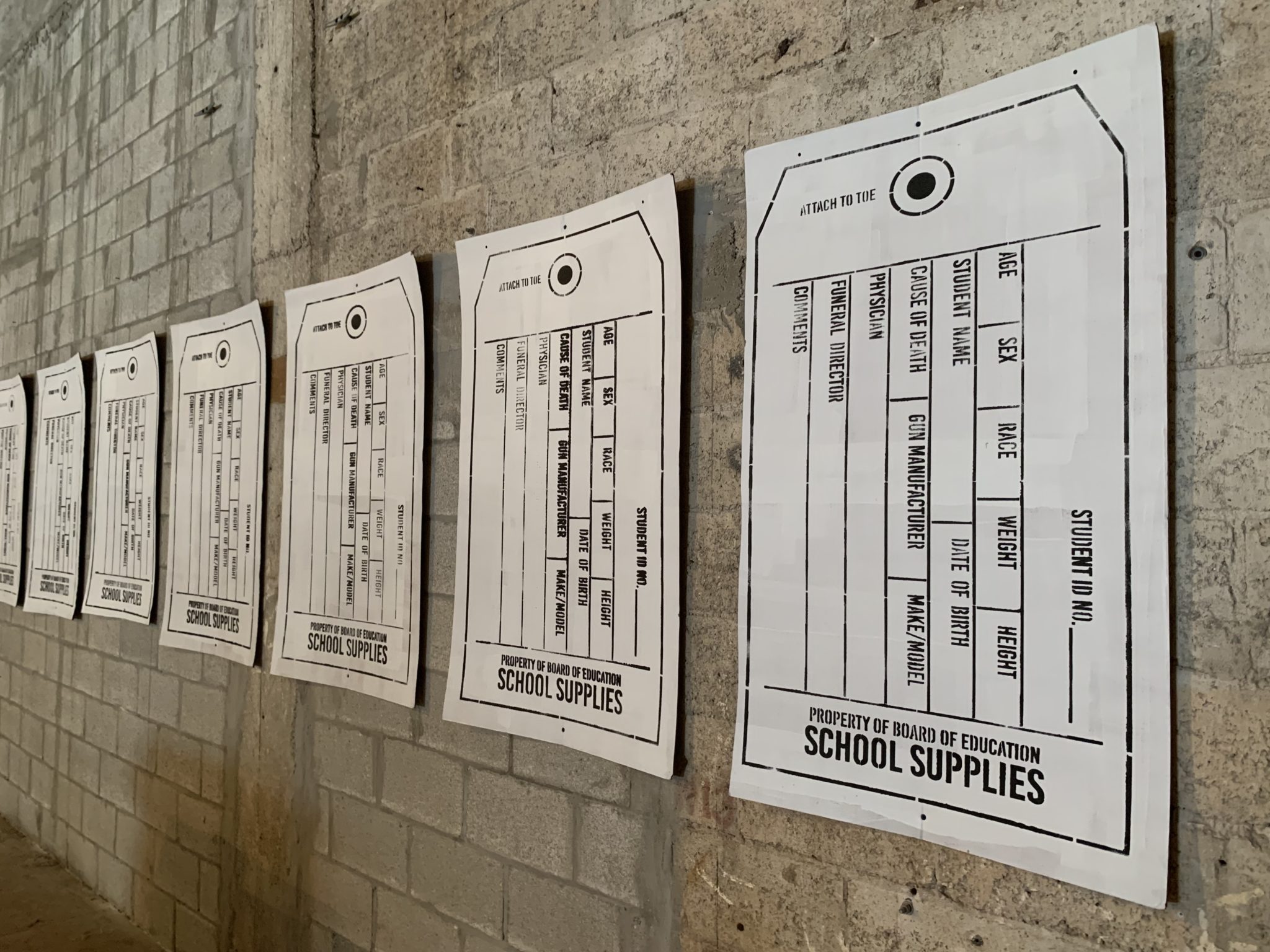

His crusade against gun violence includes large installations of body bags (opposite page) to honor young victims of mass shootings. This summer, he exhibited in FATVillage adjacent to Manuel Oliver, whose son Joaquin was killed during the 2018 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland.

“All my work has always concentrated on having a cultural context,” says Barrero, who earned a bachelor’s degree in fine arts from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. “It’s more like a page of a diary where the themes change based on current events, and I document my thoughts, my responses, to the life I’m exposed to. Everything comes firsthand.”

His current work focuses on the idea that American democracy was built by and for white people. To that end, Barrero is teaming up with fellow SAIC alum Sonia Baez-Hernandez to curate “CONstitutionX: Our Human Rights.” It is a “con” to believe the U.S. government has evolved to serve the needs of a diverse public, says Barrero, an ethnic mix of Chinese, Cuban, African Hispanic and American Indian.

“The Constitution does not pertain to us,” he says, noting his show comes from a “personal perspective because all these things affect me and people like me.”

[blockquote text=”“I’ve always participated in any protest that deals with elevating social consciousness.”” show_quote_icon=”yes”]

Barrero’s social activism is a commentary on the evolution of power. “The idea of incarcerating ethnic groups is not foreign to this country and not a new development,” he says, recalling his trips to the immigrant detention center in Homestead.

Barrero’s social activism is a commentary on the evolution of power. “The idea of incarcerating ethnic groups is not foreign to this country and not a new development,” he says, recalling his trips to the immigrant detention center in Homestead.

A full appreciation of this extensive show requires historical knowledge, especially concerning the Southern border itself. A couple of centuries ago, who was “legal” and who wasn’t could change based on treaties and wars. Indeed, Mexico ceded Arizona, California, western Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, and Texas to the United States with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican-American War in 1848. “I have identified the myth of America. Everything we assume is American was appropriated,” he says.

For the show’s finale, Barrero is borrowing from his AIDS-era repertoire. The Fabulous Fascist Fashion Show features teenage girls in quinceañera dresses who will walk the runway holding protest signs: “I don’t belong in a cage. I should be celebrating my 15th birthday.”

As disturbing as those images might be, Barrero is not a cynic. Future generations are not necessarily doomed to fight villains who judge people by color.

“While most of us seem convinced that we are stepping backwards, we are actually skyrocketing within the context of getting to know each other,” he says. “If you look at history, we’re advancing because these issues are becoming part of our daily discussions. Getting to resolve means breaking the ice and talking about it.”

Visit theboxgallery.info for more of Barrero’s work.