As much as the man born Archibald Leach tried to explain to people that he wasn’t who they thought he was in Hollywood classics like His Girl Friday (1939), North by Northwest (1959) and Charade (1963), few, if any, were buying it. How could someone so effortlessly debonair on the big screen, so utterly comfortable in his skin, so perfect as a leading man, be anything but that in real life?

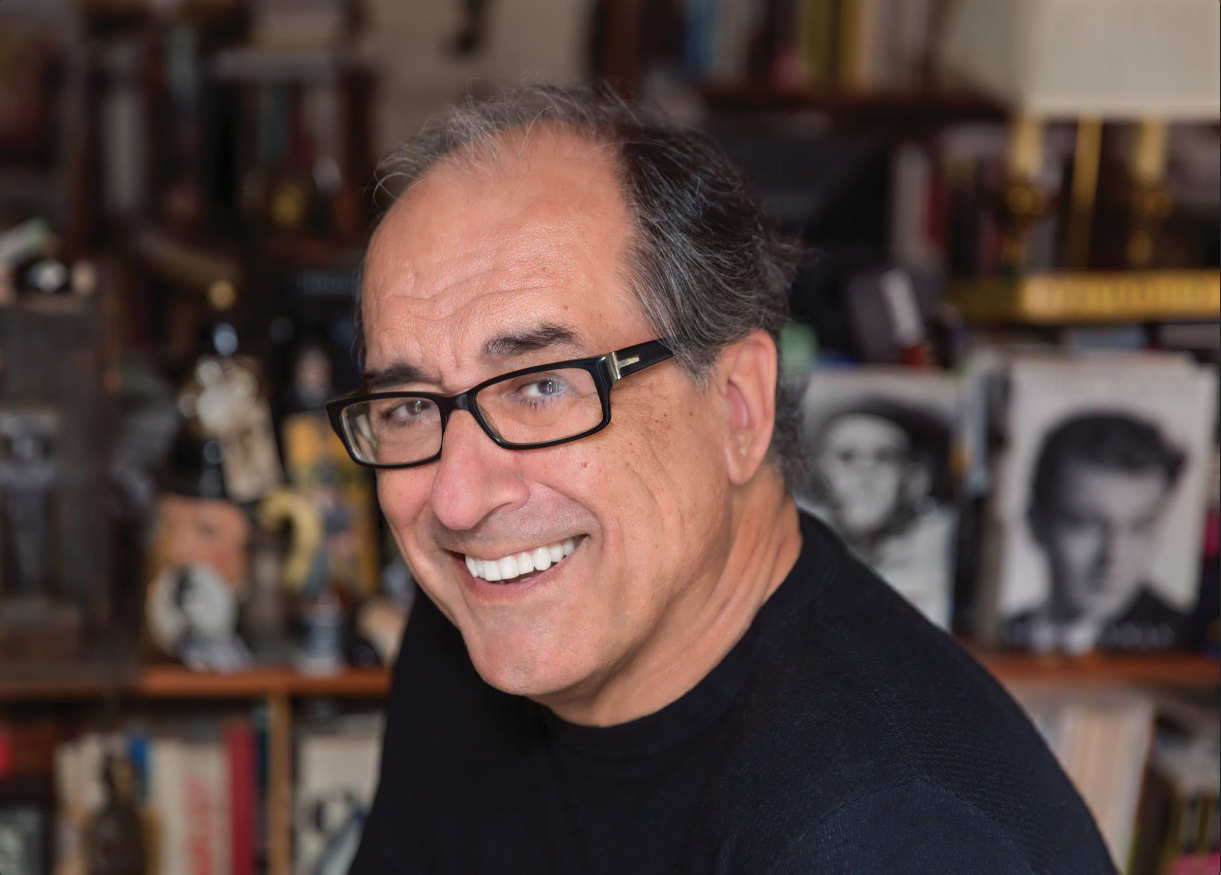

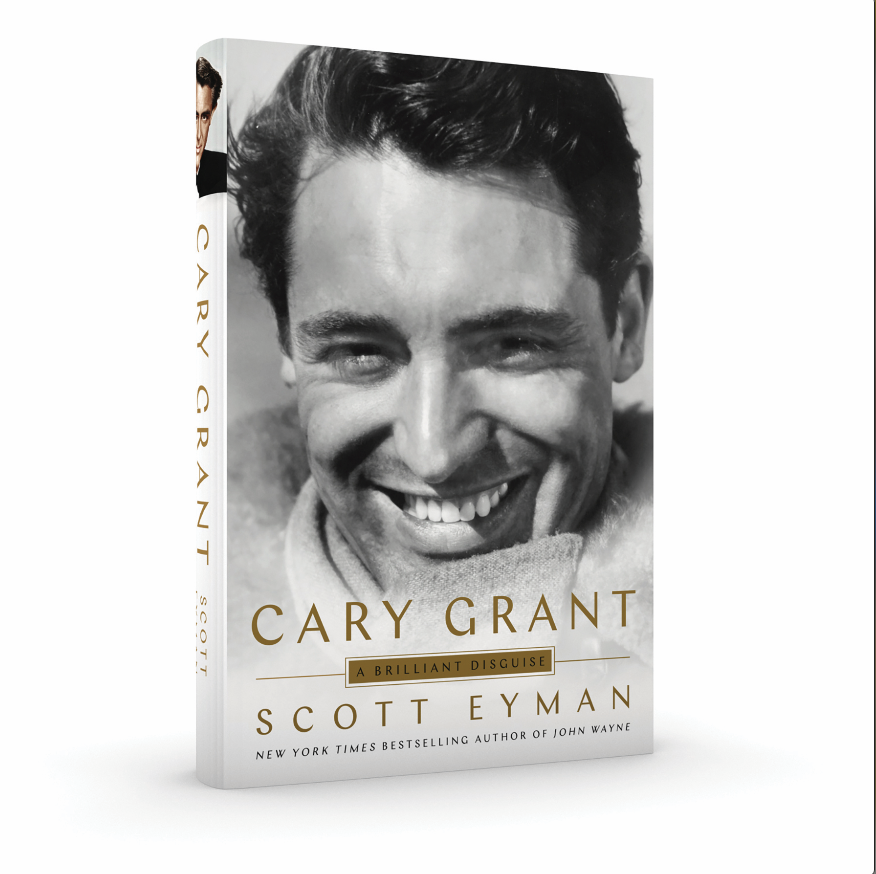

But looks, even when they belong to Cary Grant, can be deceiving. As local film historian and best-selling author Scott Eyman details in his recently released book, Cary Grant: A Brilliant Disguise, the legendary actor worried throughout his four decades in film that he would be exposed.

“I think he had imposter syndrome for much of his life,” says Eyman, who’s also authored books about John Wayne, Louis B. Mayer, Cecil B. DeMille and the friendship between Henry Fonda and Jimmy Stewart. “Because he knew he wasn’t Cary Grant.”

In A Brilliant Disguise, Eyman unpacks exactly what that means, part of a fascinating journey through Leach’s traumatic childhood in Bristol, England, and eventually to Southern California, where Cary Grant became a Hollywood icon, starring in more than 70 movies between 1932 and 1966. Eyman spoke to Lifestyle about some of what he unearthed about Grant, who died in 1986 at age 82.

You’ve been quoted as saying that part of what makes Cary Grant so interesting is that he still resonates with audiences. What is it about him and his work that transcends his era?

He’s not just one thing. He’s a brilliant physical comedian. On the one hand, he’s got very loose-limbed body language, which derives from his past as a professional acrobat. On the other hand, he’s got that raised eyebrow thing where he’s observing the madness around him with a certain distance, even though he’s part of the madness.

Then you have the duality of this underlying bleakness that comes out in dramatic parts, where he has this haunted quality. I think a lot of his acting skills derives from his control of his body. In dramas, his body language is 180 degrees from his body language in comedies. He’s very rigid, he keeps his arms to his side. He turns his whole torso rather than just his neck. So, he’s a very thoughtful actor in terms of the completion of a performance.

A lot of stars of that era perfected a single persona. Clark Gable is kind of a raffish, tomcat guy who can get all the women, and he knows it. And he played that part, more or less consistently, for 35 years. That was the goal in those days—to devise and perfect a persona. Grant colored within those lines to an extent, but he also had these startling departures—and hints of something going on underneath the surface, even in sometimes bland films.

And, of course, he’s gorgeous. Let’s not forget that. The thing about Grant is that his looks don’t date. Most movie stars are more like fashions. What resonated with audiences in the 1940s is not necessarily what resonated with audiences in the ’60s. You had this transition from movie stars being very beautiful, with exceptions like Edward G. Robinson, to movie stars who were often homely and looked like the person on the street—like Dustin Hoffman. Grant’s looks, while he’s stunning, seem to transcend periods in the same way that Edith Head’s fashions tend to transcend periods.

Grant, you’ve noted, was elusive to pin down compared to other Hollywood stars you’ve written about—in large part due to his difficult childhood. As you peeled that onion, what were some of the ways that his early experiences manifested themselves in the persona he became?

A lot of people who have early poverty are tight with a dollar, but he was tight about small things. For instance, he would lend people he loved thousands of dollars. But he would keep the rubber bands that wrapped around the Los Angeles Times every day. He had a drawer filled with those rubber bands. He would keep half-eaten sandwiches in the refrigerator, things like that. Little economies, which actually are kind of charming.

His father was an alcoholic. His mother, Elsie, was institutionalized when Grant was 11. He thought she was dead until he was [in his early 30s], when his father told him that, “Oh, by the way, your mother’s alive.” His mother had been difficult before she was institutionalized. She had lost a child, around the age of 1, before Grant was born. As a result, she hovered over Archie Leach. She wouldn’t let him out of her sight. She told him that nobody else cared about him but her. And then she disappeared one day. After Grant found out [two decades later] that she was institutionalized, he got her out of the asylum and set her up in a house in Bristol. But she was never 100 percent.

He tried desperately to connect with her, but she really wasn’t interested in a connection with him, or anybody. … I talked to a friend of his that accompanied Grant three times on yearly trips to England to see his mother. They were always very distressing for him. … [On one trip], after an hour or two, he gave up trying to talk to her, and they went back to the car. Grant sat in the backseat and goes, “I don’t know how much longer I can do this.” His friend says, “Well, she’s had a rough life. Maybe with time.” And Grant says, “I don’t have any time.” At this point, he’s in his 60s and his mother was in her middle 80s. It was a shadow that hovered over him his entire life.

So, in Grant’s experience, love had too high of a price. His relationships were all seduction, retreat. Seduction, retreat. He didn’t really trust love. And it never came back to him in the amount he needed it. So, he would seduce women, and then he would back away. There was no consistent day-in, day-out response from him to his love interest. His relationships tended to break up because the signal kept fading out. And I think that’s a result of his childhood and his indoctrination by his mother.

Pauline Kael once wrote that Grant was “the most publicly seduced male the world has known.” Is what you’re describing part of the attraction? That he was so unavailable?

On screen, he usually devised it so that the female character would pursue him; Bringing Up Baby and His Girl Friday being the classic examples. … He rarely evinces desire for a woman in his films. Even Grace Kelly pursues him in To Catch a Thief.

In life, he would pursue women. But he wouldn’t be consistent about it. Once the deed was done—and they had sex, or she moved in, or they got married—then he would kind of disappear into himself. The woman is wondering, “What did I do wrong?”

Nothing really. But this happened over and over and over. It happened with wives, it happened with mistresses. That was the way he was.

What do you think that Alfred Hitchcock drew out of Grant that made their collaborations so interesting?

Hitchcock drew out the bleakness in him. Grant had a very bleak early life; his childhood was dreadful by any stretch of the imagination. The only Englishman I can think of who had a worse childhood was Charlie Chaplin. So, Grant could tap into that when he had to, but I don’t think it was his favorite thing. I think it was difficult for him to access the fear and anxiety that he had as a child—and it was hard for him to dispel it once he accessed it.

But Grant and Hitchcock also understood each other on a deeper level. They were both lower-middle-class Englishmen of whom nothing was expected. Hitchcock also understood that Grant was a professional charmer. There’s a moment in the book where Hitchcock is speaking to a class of writers at Oxford, and he’s talking about how the camera reveals character. People felt Grace Kelly was likable, and, it’s true, Grace Kelly was a very likable person. But they rejected Tippi Hedren because, in fact, she was not terribly likable. Hitchcock said there’s only one actor who’s so greatly gifted that he can appear likable when, in fact, he’s not. And someone in the class said, “Cary Grant?” And he said, “Exactly.”

So, Hitchcock understood the gap between who Grant was offstage and who he was when he flipped the switch on—because he had to deal with him when he flipped the switch; they made four pictures together [Suspicion in 1941; Notorious, 1946; To Catch a Thief, 1955; North by Northwest, 1959]. And if you read the correspondences from the production managers and assistant directors, it wasn’t easy. Grant was a touchy, difficult actor who worried a great deal about everything.

Hitchcock understood that—and put up with it—because Grant, to him, was the perfect leading man for an Alfred Hitchcock movie. Just as John Ford thought John Wayne was the perfect leading man for him. When you find that guy, or that woman, who perfectly embodies what you want to put on the screen, you stick with them—unless they’re absolutely crazy.

Grant wasn’t crazy, he was just a handful.

When Grant quit show business at age 62, he quit for good. Is there anything in your research that suggests he had regrets about that?

He never doubted it for a minute. I think, if he had it to do over again, he would have quit sooner. The proximate cause was the birth of his daughter. He adored children, he wanted children all his life. And he never had them until he married Dyan Cannon and they had Jennifer [in February 1966; two years later, Grant and Cannon divorced].

But he also had been a little bit bored for some time. And it shows up in some of his choices, like That Touch of Mink [a 1962 romantic comedy with Doris Day], where he was clearly disengaged. … And a stiff like Walk, Don’t Run [a 1966 comedy], which unfortunately is his last film and doesn’t have a breath of life in it.

He also was worried about his looks and working with actresses that were 35 years younger than he was. It didn’t bother him in life, but it bothered him in terms of the juxtaposition on screen. He thought he was pushing his luck.

How did Grant become involved with LSD? What were you able to discover about the effects of those sessions on him?

He went into it because nothing else had worked. He had spent 50 years trying to assimilate Archie Leach and Cary Grant. Psychotherapy hadn’t worked. It took too long, and it wasn’t a good fit for his psychology.

So, he was looking for something—anything—that might help. It’s the late 1950s when he starts using it; back then, it was still a legal substance. A lot of people in Los Angeles had been using it since the 1940s. And Grant found that it helped.

At one point, early on, in one of the first trips he took, he [defecated] all over the floor. Not metaphorically. Literally. He came to see that as a transcendent moment because it symbolized for him what he had to get rid of. He had to get rid of his past. He had to get rid of being hung up about his mother and their inability to make a connection. He had to get rid of being hung up about Archie Leach. He once said, “Cary Grant really didn’t have any problems. Archie Leach had problems.” He was no longer Archie Leach—except, of course, he was. In his mind, he still was Archie Leach.

According to him, acid made all the difference. Grant did well over 100 trips. At first, they were supervised. Later on, he would do it at the house, without supervision. And he would advise other people about doing it. He thought it was positive and that almost anybody could benefit from it.

For Grant, it helped to unify him. It helped to relax him. And it helped him accept who he was. Outwardly, it didn’t affect his nervousness or his anxiety about the scripts. And the people that worked with him before and after acid didn’t really notice that much difference; he was still a pain in the ass.

But inside, he felt better.

Featured image: An RKO publicity photo of Cary Grant connected to his 1941 film, Suspicion