Think back to when you were 5: You might have been able to walk safely to school, unaccompanied by your parents; perhaps you were free to run around the neighborhood or play in the backyard until Mom called you home.

Think back to when you were 5: You might have been able to walk safely to school, unaccompanied by your parents; perhaps you were free to run around the neighborhood or play in the backyard until Mom called you home.

Darius V. Daughtry also has memories from that time. One is seared into his mind.

He had gone with teenagers to an empty house two doors from his grandmother’s. Like many adolescents, the kids wanted to exercise their independence and play music. Going inside for a few hours seemed harmless. That is, until the Fort Lauderdale police came and rounded them up.

“The handcuffs were too big for my wrists, and they called me a little [racist expletive] for doing nothing,” recalls Daughtry, a teacher, writer and advocate for social justice. “It was kids hanging out. In America, it’s OK unless those kids are black, unless they are poor, or [part of] the Latinx community. Certain groups are criminalized for otherwise normal behaviors.”

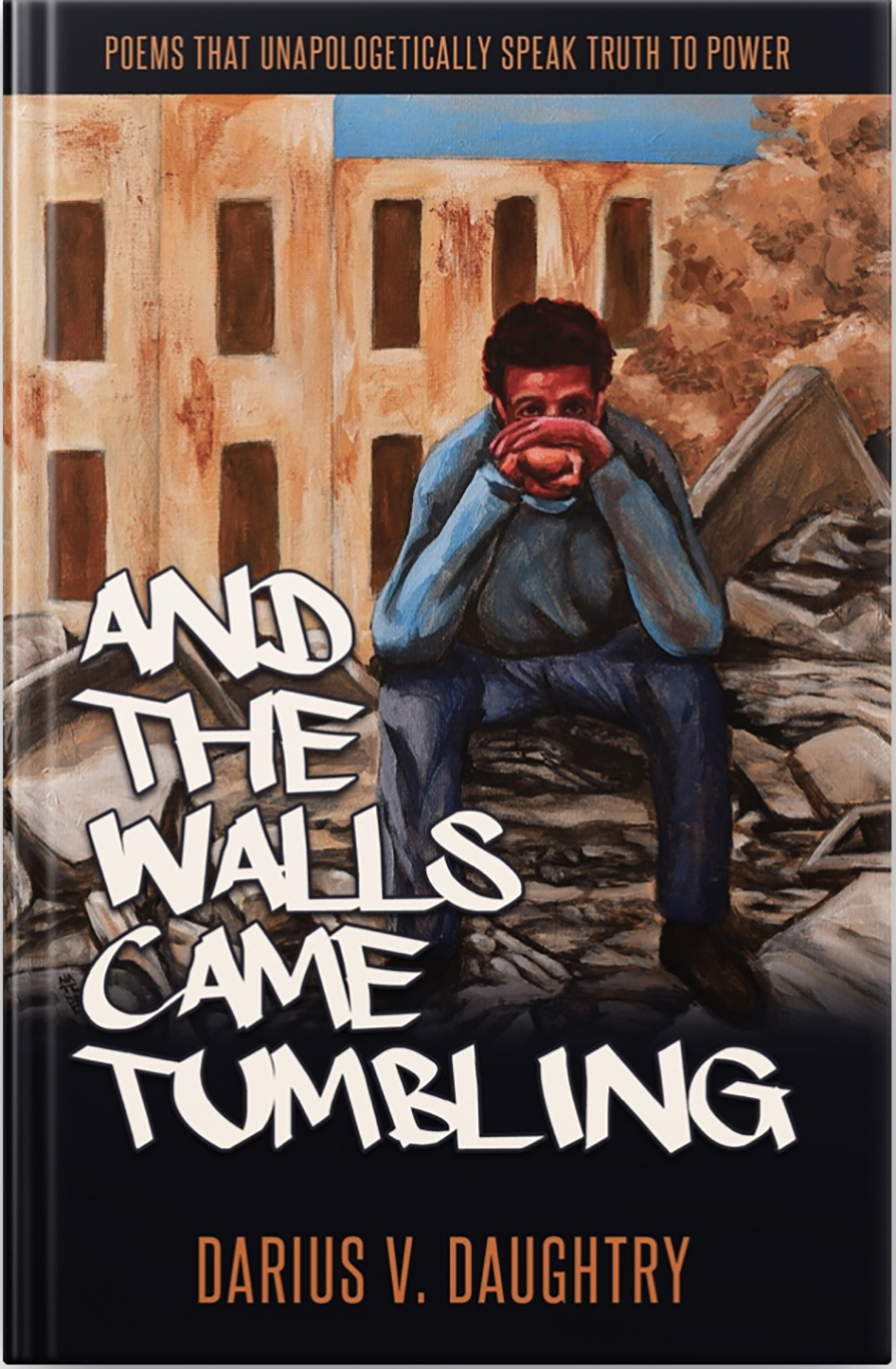

The more he’s seen and experienced over the years, the more he’s convinced that American systems—capitalism, the courts, democracy—work for white people, who created them on the backs of slave labor. These injustices transform into free verse in his first book of poetry, And the Walls Came Tumbling, published earlier this year by Omiokun Books.

When he unveiled the book in January, he held a party in the Project Space in FATVillage. Tall, broad and full of smiles, he diffused his energy across the warehouse as he danced onto the stage to Marvin Gaye’s “Got to Give It Up.” People moved and sang to celebrate his achievement.

But he and the audience also were there to celebrate a triumph of a more-existential kind. As a black man, he has survived arrests and harassment. He sat on the stage to read poems to his niece and nephew, reminding them life isn’t fair, it’s dangerous, but they are beautiful. The rawness of his words, their pristine placement on the page, speak to high art that emerges from his own trauma as much as it does the album on which “Got to Give It Up” appears.

“[Gaye] is lamenting the experiences, the sorrows and violence that exist in inner-city communities, the violence during the [Vietnam] War … drug use and environmental devastation,” says Daughtry about the 1971 album “What’s Going On.”

“He’s a man known as a soulful, sexy singer, but he’s saying, ‘I am an artist making great experimental things, but I’m going to stand up and sing about things that really matter.’ My charge as an artist is to shed some light on some [expletive].”

[blockquote text=”I was born of “Fight the Power” & “F— the Police.”

But they try to beat “Don’t Worry, Be Happy” into the brown boy.

Into the “don’t move or make a sound, boy.”

Into the 8 barrels pointed, 8 pins locked, 8 trigger fingers cocked,

now, get on the ground, boy.

—Excerpt from “P.E. and N.W.A. = ME,” from And the Walls Came Tumbling” show_quote_icon=”yes”]

So profound are the poet’s connections to the musician, that he jokes about being his son. Spiritually, it certainly seems that Daughtry is a living legacy. As founder and executive director of Art Prevails Project, a nonprofit partly funded by the Broward County Cultural Division, he provides numerous storytelling opportunities for people of color.

“The Happening: A Theatrical Mixtape” is a multidisciplinary theatrical performance rooted in social issues such as misogyny and daily violence in poor communities. “Speak No Evil” is Daughtry’s short play centering on a dystopian reality where freedom of expression has been outlawed—“which was kind of scary with how real that was,” he says in reference to President Donald Trump’s demonization of professional journalists and critics.

Daughtry also points to the president’s remarks that there were some “nice people” among the white nationalists carrying torches at the deadly 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia.

“If you don’t react, I can’t tell the difference. In my book, you are them,” he says. “You might not punch me in the face and call me a monkey, but if a person does and you keep walking by and act like it didn’t happen, you might as well have punched me in the face and called me a monkey. I see you as the same ilk.”

Visit dariusdaughtry.com for more of Daughtry’s work. He will be reading from his book in late November at the Miami Book Fair; check out miamibookfair.com for the date and details.

Lead photo by Eduardo Schneider