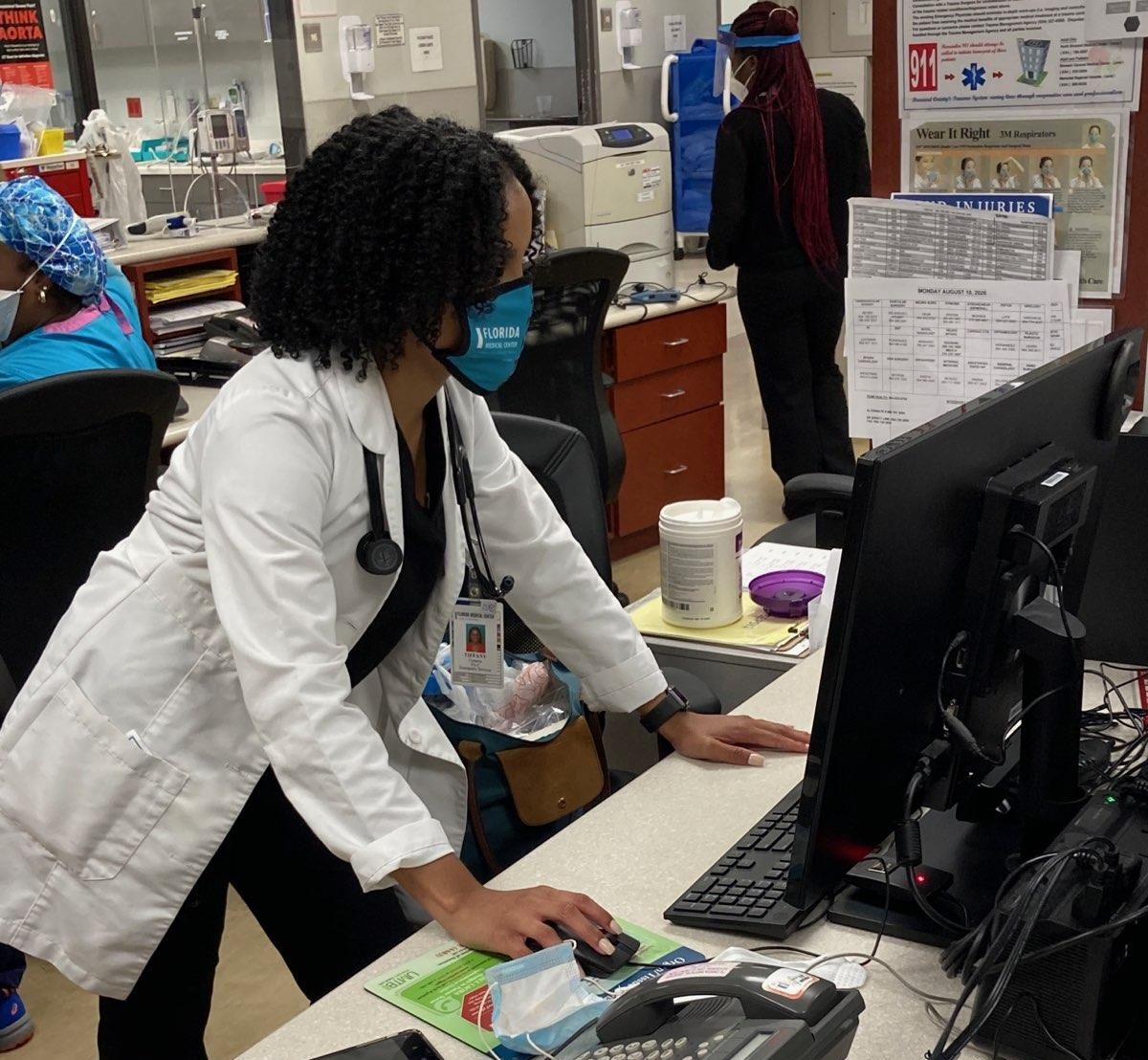

Tiffany Comerie

Physician Assistant, Emergency Room, Florida Medical Center

Background: Tiffany Comerie grew up in Coconut Creek after moving from Jamaica when she was 6 years old. The Coconut Creek High School graduate majored in biology at Florida Atlantic University, where she decided to become a physician assistant. She attended Nova Southeastern University and moved back to Creek in 2013. She has worked in the emergency room of Florida Medical Center in Lauderdale Lakes since 2014.

Pandemic story: At age 7, Comerie’s body wasn’t producing enough platelets. She had to have platelet infusions, she bruised easily and she spent holidays at Joe DiMaggio Children’s Hospital. Doctors don’t know why the condition, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, occurs, but Comerie knows that it gave her a certainty that drove the rest of her life.

“That’s kind of how my path was shaped—because of what I experienced and the fact that I was in and out of hospitals, and I interacted with so many medical providers during that time,” says the Creek resident, now 31. “I felt like they did so much for me when I was younger. That’s where I got my push to be in medicine.”

Today, the physician assistant and her team at the ER of Florida Medical Center are plagued by the mysteries of COVID-19, which Comerie started following in February. From March through June, Comerie says the ER’s increase in volume came mostly from those living in nursing homes and assisted living facilities. Then, the spike arrived at the end of June, when, for the first time since she started working there in 2014, Comerie saw the ER reach capacity several times.

That’s also when she saw more younger patients, people in their 20s, 30s and 40s, including a 19-year-old who developed myocarditis as a result of the virus.

“At moments, it could be very stressful, especially when … there were just patients everywhere, and you have to choose, at that point, who is the most important, and who needs to be assessed first. And everybody else has to just wait.

“It was very hectic trying to keep the COVID versus non-COVID [separated]. We started testing everyone that was admitted, whether it was for a COVID reason or not. We saw a lot of positives in people who were not there for COVID symptoms. That was a little scary because you don’t even know if this person with a laceration has COVID. So you have to then protect yourself from everybody.”

As Comerie saw more and more people become ill, she started dealing with feelings about her own health. Could she get sick with the virus? Could she be asymptomatic and infect others, even though she was wearing personal protective equipment? She avoided visiting her mother and her 85-year-old grandmother in Palm Beach County as well as a pregnant friend and her sister, who also lives in Creek.

At the hospital, the more personal parts of care were also difficult to deal with: seeing patients close to her age and watching them videochat with their families when visitors weren’t allowed in the hospital—all while not knowing what could happen in the next 48 hours.

“With some people I was concerned about, I’d get to my shift and say, ‘Let me see what’s going on with this patient.’ And then I would see that they passed away. I would be like, ‘But they were fine.’ That was to me the hardest: I left here and you were alive. You were kicking. I came back, and now you’re gone. …

“The hardest part was just knowing that you did everything for that patient, and it still wasn’t enough for them.”

To deal with the life-and-death realities of the pandemic, Comerie says she mentally walks herself through the day before physically doing so, giving herself a pep talk in the mirror every morning. She tells herself, “Tiffany, you can do this. … You’re still going to work every day doing what you can to the best of your ability.”

On the sleepless nights when Comerie wonders if she did everything she could do for a patient that day, she looks at the positives: the patients who still need her, the ones who were able to go back home to their families—and the knowledge that “this will get better.” Maybe not normal. But better.

In the meantime, she’s not backing down.

“Even if I’m putting myself at risk, I always want to help. I think this is what I was made for: to help people. …”