For an organization that deals with some of life’s grittiest real-world dramas, ChildNet sure knows a thing or two about circus-like feats. As the lead agency for community-based care in Broward (since 2002) and Palm Beach counties (since 2012), the esteemed nonprofit organization manages to keep hundreds of child-welfare plates spinning at any one time.

In layman’s terms, as president and CEO Larry Rein explains, ChildNet is responsible for every youth in the two counties who’s been adjudicated “dependent” by a circuit court—meaning, without proper care—following an investigation of abuse, abandonment or neglect. According to the Florida Department of Children and Families, ChildNet was serving a combined 2,100 children and young adults with out-of-home care needs in Broward and Palm Beach counties as of Feb. 28.

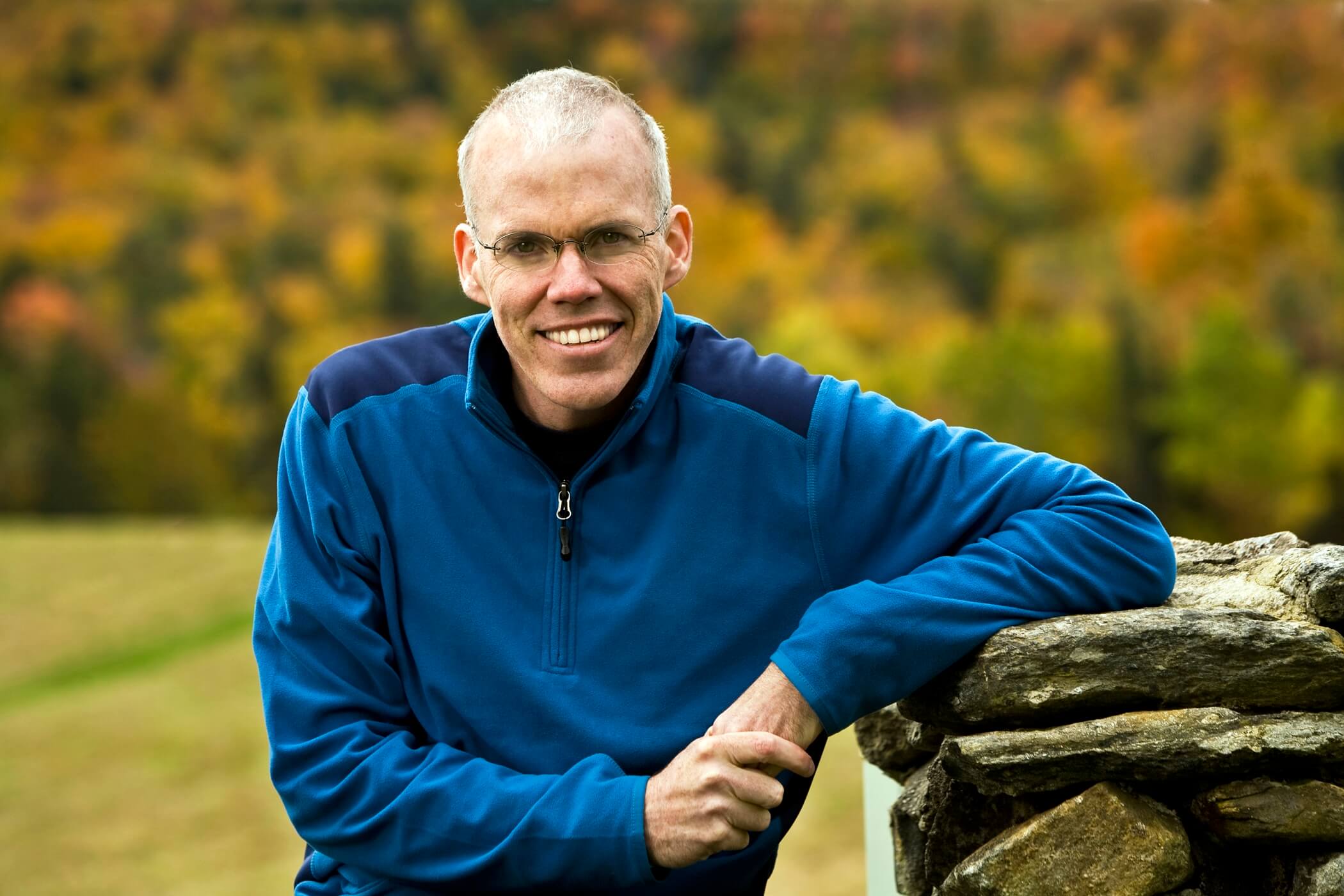

“Essentially, we’re the umbrella organization that manages a system made up of other nonprofits and service groups [involved in child welfare],” says Rein, one of South Florida’s most ardent advocates when it comes to community-based care. “We have about 230 case managers between the two counties. We also subcontract with different organizations to recruit foster parents, to train and license them, to operate shelters, to operate group-care programs, to arrange adoptions, to do independent living services, to provide behavioral health-care services, and to prepare kids for when they transition out of foster care at 18.

“We coordinate that entire system.”

If it all sounds daunting, it can be at times. But thanks to Rein’s tireless and innovative efforts, ChildNet continues to expand its web of support and services—making a difference, along the way, for countless children and teens. Lifestyle spoke to Rein for its issue in May, which is National Foster Care Month.

In this edited version of the Q&A, Rein addresses a continued challenge for ChildNet; check out the May digital edition of Lifestyle for the full interview.

The transition into adulthood for foster care youth remains a core challenge for the system. What steps can ChildNet take to make an impact?

The support to kids in terms of transitioning out of foster care has improved dramatically over the last 20 years in Florida. Still, we have so much further to go.

I’m in the middle of a project that’s focused totally on this. There are a lot of organizations, especially in Broward, that provide services for kids to prepare them to transition to adulthood—for both foster care teens and kids not necessarily in foster care.

We’re in the process of trying to determine exactly how effective these services really are. Are we sending our kids to the right program? And are those programs meeting the unique needs of ChildNet’s foster-care children? We just began a deep dive into this issue. This is bigger than ChildNet; it’s throughout the social service industry.

I don’t think we go deep enough into being sure we’re doing the best and the most that we possibly can for these kids. People sometimes assume because they’ve been doing it one way for years, that’s the only way to do it. And I think people get a bit stale. We’re trying to be sure that we’re giving our kids exactly what they need. If we’re not, then we need to figure out what they need—and go create it.

When your head hits the pillow, is that the issue that keeps you up at night?

This isn’t true of every foster-care teenager, but there are some who’ve had incredibly challenging lives. Many of those kids have long delinquency histories, as well as foster-care history. They probably have little, if any, relationship with family at this point. So, their needs are enormous. That’s what I’m concerned about. Are the people providing the services up to really doing what we need for these kids?

I feel we’ve done a good job over the past two decades. But the thing we haven’t done as well is to provide for those kids, the most challenging teenagers.

So, we did a little pilot program in Palm Beach, our Oak Street project. It was [an idea] by me and a circuit court judge. We had four of the most challenged young men in the dependency system—all four have long delinquency records—living in a home with a lot of staff, a lot of community support, and a lot of educational support. Over the past few years, we saw an incredible drop in the number of arrests—to virtually none. An incredible increase in their attendance at school. A tremendous increase in their performance in school. And a decrease into their admissions for mental health issues and residential treatment.

All in all, it’s been a rousing success.

But now, in the last six months, we’ve had our first “graduates” turn 18. At 18, the system is set up to provide them some support, but they’re no longer dependent—and we can only use certain funds provided through the federal government to help support them. There are some programs for them that will provide support, but it’s not the same level of support that they’re used to.

For all the success we’ve had in the last two years in turning their lives around, we’re now seeing that they’ve floundered since they’ve left the [Oak Street] program.

We do a lot of great stuff for the typical child [in the system]. I think we prepare them for independent living. But for these more challenged teens, we need to start a lot earlier at getting them ready to be on their own. And then, after they leave us, there needs to be far more support for them than there currently is in terms of supervision, and an adult to connect with and really depend upon.

Nobody has been able to figure out a way to serve the really tough cases. We’re having these discussions now. We’re trying to replicate the Oak Street project in Broward with a home for boys, and soon we’re going to open a home for girls.

I’ve been trying to get legislative appropriation, because I don’t have it in my budget to do another home. We got it through the state legislature last year, but the governor vetoed it. Hopefully, it’ll work this year. But the cost is enormous.