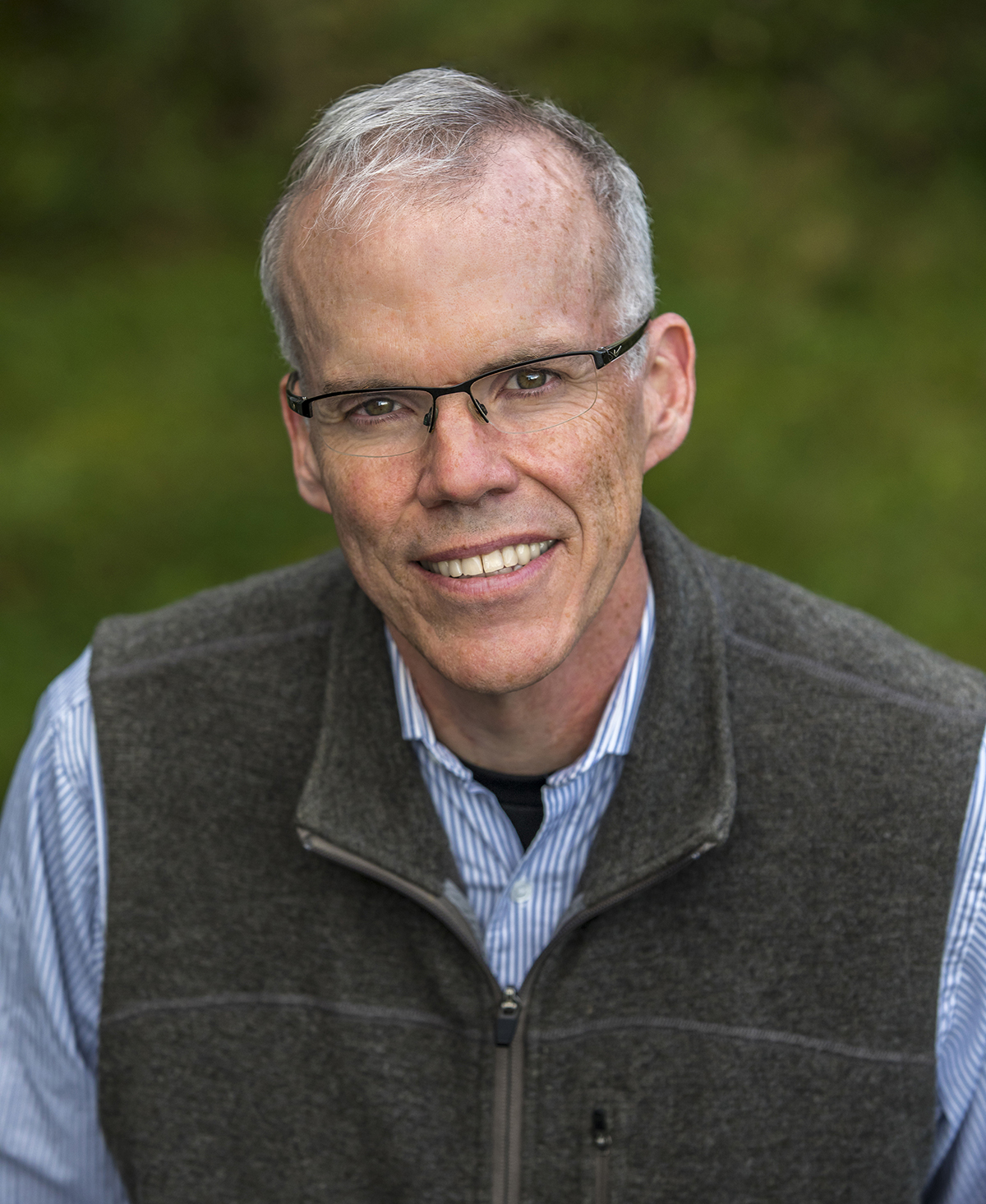

What started at age 54 as a New Year’s resolution has evolved into a life-altering linguistic exploration that continues to bear significant fruit. In 2017, having already stepped down as CEO of Levenger after 27 years, Steve Leveen launched America the Bilingual, a passion project that celebrates the pursuit of bilingualism in America—and touts its potential to empower and unite our citizenry.

What started at age 54 as a New Year’s resolution has evolved into a life-altering linguistic exploration that continues to bear significant fruit. In 2017, having already stepped down as CEO of Levenger after 27 years, Steve Leveen launched America the Bilingual, a passion project that celebrates the pursuit of bilingualism in America—and touts its potential to empower and unite our citizenry.

Earlier this year, Leveen published America’s Bilingual Century, a thoughtful, entertaining and scholarly work that encompasses 12 years of research and expert interviews. In it, he seeks to enlighten Americans about bilingualism by sharing his own journey, detailing the advantages of speaking multiple languages, and debunking 12 language myths.

Leveen had plenty more to say about the subject during an interview with Lifestyle for the June issue (first of two parts).

Beyond learning another language, has bilingualism opened you up in ways that, perhaps, you didn’t anticipate?

Learning another language as an adult requires [an acceptance] to be vulnerable. You have to be willing to speak like a child again—and to get the help of adults who know that language. As [research professor and best-selling author] Brené Brown has shown the world with her work on this topic, being vulnerable is to exhibit an unusual power. People may think it’s showing weakness.

But it’s actually a very powerful thing, both for yourself and for others. It’s inspiring when an adult is willing to say, “Hey, how do you do this? Can you help me?”

Learning another language is also enjoyable because it opens you up to the world—and to an appreciation of others that you may not get if you limit yourself to only one language.

The concept of fear is prevalent in some of the myths about bilingualism that you debunk, including people who feel they’re just not good at learning languages. Is the challenge for those people simply taking that first step?

It can be. I think the bigger challenge for people is that they don’t want to be stupid.

As an adult, we can understand this. Who wants to come across as making lots of mistakes? We pride ourselves as adults on not doing that. I interviewed Luis von Ahn, the founder of [the language-learning platform] Duolingo. He said that 20% of language learners have no problem [making mistakes]. They’re the ones who learn quickly. Eighty percent of us have a big problem with coming across as sounding silly. And we learn more slowly.

My advice to people is to use Duolingo, use other software, and read and watch television in your newly adopted language. Do all those things. But recognize that language is meant to be used in the wild. The purpose of Duolingo is to get people comfortable enough so that they start having real conversations with real people. That’s why we’re learning another language in the first place.

In the book, you quote comedian Trevor Noah, who says that when you make an effort to learn a language, you’re saying, “I understand that you have a culture.” On the flip side, what message is sent when people don’t bother to pick up a phrase or two when traveling to a foreign country?

It’s the opposite of what Trevor Noah said. It’s saying your language and culture is not important, thus, you’re not important. That’s something I didn’t realize when I started on this research. I was sort of embarrassed to use phrasebook language. I thought, why go out of my way to sound like an idiot?

But after interviewing so many bilinguals, I found that the more languages that they spoke, the more they were sure to use phrasebook expressions and niceties, the polite expressions of “thank you,” and “good morning, and “good evening”—phrases that I call the buds of bilingualism. They go so far. You might say, never has so much goodwill been generated by so few words.

It’s interesting how language, for a variety of reasons, has the potential to become an emotional topic in this country. Why is that?

I think part of it is that we have this old narrative that says, you must forget your languages. When some Americans hear other languages being spoken in the country, or when they see billboards on [Interstate] 95 in Spanish, they mistakenly assume that the [non-native speakers] can’t understand English. What they don’t understand is that, in almost all cases, these people can speak English. There are just certain realms of their lives where they prefer to speak Spanish.

One of the things that makes the United States unique is that we are a nation of immigrants. And the old narrative that we had as a nation was that to become a proper American, it was necessary to throw off the language or languages that you came to this country with, and speak English—and only English.

And that’s what American immigrants did, particularly in the first part of the 20th century. It was the practical thing to do. You and your children were not going to use the heritage language much anymore. The chances of you going back to the home country, when you had to go by ship, were slim to none. And the communication technology of the day consisted of letter writing.

Not only that, but all the education in the United States—which was leading the world in public education in the first half of the 20th century—was conducted in English. So, immigrant parents and grandparents were very gratified to see their children become the most educated members of their family and becoming literate in English.

But the equation changed around the 1960s when inexpensive air travel became prevalent, and communication technology started to improve. Today, the practical thing for immigrant parents is to keep the heritage language alive—because they can return to their original country. Cousins can speak to cousins. And communication technology today is ubiquitous, free and in real time. So, for today’s immigrants, it makes sense to raise their children to be bilingual. They’ll have better opportunities and better careers with that skill.

Americans are a practical bunch. We always have been, sometimes to the amazement of Europeans. And the practical thing today is to raise your children as bilingual for the advantages. The really thrilling part to me is that it’s not just immigrant parents who understand this. It’s all parents. Native-born parents also recognize that there are advantages for their children to be bilingual. So, immigrant parents and native-born parents are united in this sense. That’s why they’re clamoring for dual language schools, and so on.