The gaudy career statistics that Dan Marino posted during his 17 seasons as quarterback of the Miami Dolphins (including 420 touchdowns and more than 61,000 yards passing) were never meant to endure in the pass-happy National Football League. However, the same can’t be said for the formidable numbers—and lasting impact—connected to the Hall of Fame quarterback’s nonprofit organization.

In serving more than 500,000 individuals and families since its inception in 1992, the Dan Marino Foundation has helped to change the national conversation around developmental disabilities. What started as a frustrating search for resources and answers by Marino and wife Claire after their second son, Michael, was diagnosed with autism, has evolved into an innovative and multifaceted effort to not only raise awareness but to provide every-day solutions.

Along the way, the foundation has moved the needle through a variety of successful initiatives, including the Marino Autism Research Institute, launched in 2005 to support joint studies between the University of Miami and Vanderbilt University in Nashville. In Fort Lauderdale, the Marino Campus continues to prepare young adults with developmental disabilities for employment and independent living through post-secondary schooling. On the technology front, along with the premiere of online learning next spring, the foundation currently boasts an interactive tool that allows individuals to practice and become more confident at job interviewing.

On the heels of its recent fundraising announcement—the advance sale for a Dan Marino Campus specialty license plate (see sidebar below)—Marino and the foundation’s CEO, Mary Partin, spoke with Lifestyle about the organization’s three-decade journey as well as the ongoing challenges facing those with developmental disabilities.

What do you remember about three decades ago when Michael was diagnosed as far as the resources available to you and Claire?

Dan: We knew something was up because Claire’s mother was a former nurse. She felt like we needed to get Michael checked out. There’s was something going on, and we had no idea. We went to the University of Miami, and we got the diagnosis of autism. I remember coming home and trying to look up information. We soon realized that we had hardly anything [in terms of resources], except what the doctors were telling us.

Didn’t your search for help lead to the launch of the Dan Marino Foundation?

Dan: Yes, it did. We started the foundation [in part] just to help as far as creating recognition about autism. I remember the budget for the national [organization] connected to autism back then was something like $5,000 for advertising. I couldn’t believe it. As parents, Claire and I wanted to do whatever we could to not only create awareness, but also to find ways to give Michael and other children with developmental issues their best chance at success.

Mary: That’s really the impetus behind the Dan Marino Outpatient Center. Fortunately, Dan and Claire were able to [seek out] different specialists. But they really wanted to bring those kinds of services here to South Florida. That began their work with Miami Children’s Hospital in Weston to build the Dan Marino Outpatient Center in 1998. [Note: The hospital was renamed the Nicklaus Children’s Hospital in 2017; the Marino Center was the first facility to offer comprehensive services to children with neurodevelopmental challenges.]

Dan: What we wanted to create is a place where it’s like one-stop shopping; you can get a diagnosis, treatments, information, all in one place. We realized that [such a place] was nowhere to be found in South Florida. That’s where that all started, and it was really Claire’s idea. We eventually developed it into what it is now. And I believe it’s been a huge success.

I have mothers and dads who talk to me about how the facility has changed their lives and [the lives of their children with developmental disabilities]. And it makes you feel so proud because [the work of the foundation] has given those families an opportunity to let their kids develop in life.

How did creating that early awareness help to change the conversation around developmental disabilities?

Mary: It’s worth remembering that, back when the foundation first started, there was such a stigma about autism. People were not talking about it. But during that time, Dan and Claire did a commercial with Michael that had such an impact.

Dan: It was a commercial that we did with the NFL for the United Way; it would play during the Sunday games or during Monday Night Football. I think it really helped to raise awareness around the country.

Mary: I still have people come up to me and say that commercial was a defining moment. They knew something was wrong with their child, but they couldn’t figure it out. After seeing Claire and Dan share their story, people were more willing to seek help for their kids. The early intervention is what it’s all about. It makes such a difference.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2020 report from the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network indicated that 1 in 54 8-year-old children were identified as on the spectrum. The Marino Foundation notes that 1 of every 7 people in the U.S. has a developmental disability. Why is that statistic so crucial as it pertains to the foundation’s work?

Mary: It’s important because it really broadens the scope of the message. Autism is [one of many] developmental disabilities. Everything that we’re doing for people with autism translates to any developmental disability. In fact, when it comes to later-life issues—like the employment programs we have—we’ve actually transitioned that into working with kids who’ve aged out of foster care, as well as young adults in the juvenile justice system.

That’s why we use that statistic. These days, many people know someone with autism. But even broader than that, they know someone with a developmental challenge—so that plays into how many people can be affected.

Why was it important for the foundation to start focusing on employment and independence of young adults on the spectrum—and did Michael’s journey into adulthood influence that?

Dan: After kids finish high school, how are they going to transition into [adult] life? As Michael went through that [period], we realized that we wanted to have a place—a campus or programs—to help kids get jobs, teach them life skills, all those things that will be important as adults. Just having that support is so important to these kids as they begin to go out in the community. And we see all the time how much they love [working and contributing].

Mary: Ten years after opening the Dan Marino Outpatient Center, the parents and families we had been serving were calling and saying, “I have a 17-year-old who has transitioned from school, and now he’s home sitting on the couch.” There were just no opportunities. Less than 8% of American companies hire people with disabilities. [Note: Prior to the pandemic, estimates typically placed the unemployment rate in the United States for college-educated people with autism at roughly 85%.]

But we knew these young people had the ability to work and add to the workplace. And that really began the transition and looking at that focus. We haven’t forgotten about the Dan Marino Center; there are 29,000 visits annually in Weston. But we needed to look at the needs.

In the same way that, 30 years ago, nobody was talking about autism in general, we found that there were no programs and no dollars being applied toward employment for young people with developmental disabilities. No training, no job interview coaching. We’ve always wanted to put our dollars where they’re going to have the biggest bang for the buck.

So, we started with summer employment programs, and then we did career services, where we assisted young people with attaining competitive employment. That led to the opening of the Marino Campus in 2013 [the post-secondary school that offers that bridge to employment].

What are the misconceptions that you still confront from employers reluctant to hire someone on the spectrum?

Mary: [Some employers] think that it’s going to add to their insurance premiums because this person has a disability. Or they think the person will be less productive. Or they’re going to take more days off. Or they worry about needing technology modifications and the expenses [associated with that].

But the reality is that there a study by Accenture, a global professional services company, that showed that companies saw great improvements when hiring people with disabilities—like 72% more productivity, 30% higher profit margin. Regarding the culture of a company, there’s also something about introducing people with different abilities into a work site that changes how people feel. There’s no science to it, but people seem to get nicer or more empathetic.

Do you think Michael’s own involvement in the foundation has had an impact on him?

Dan: I think it’s been extremely positive from the beginning. We’ve been blessed that Mike has really developed into a very high functioning kid on the spectrum. If you’ve ever been around him, you wouldn’t think he ever had an issue. But his impact really has been as [an example] to other kids.

Mary: He’s a role model now. Michael is married, and he has his own life. And that means a lot for people working toward that kind of independence.

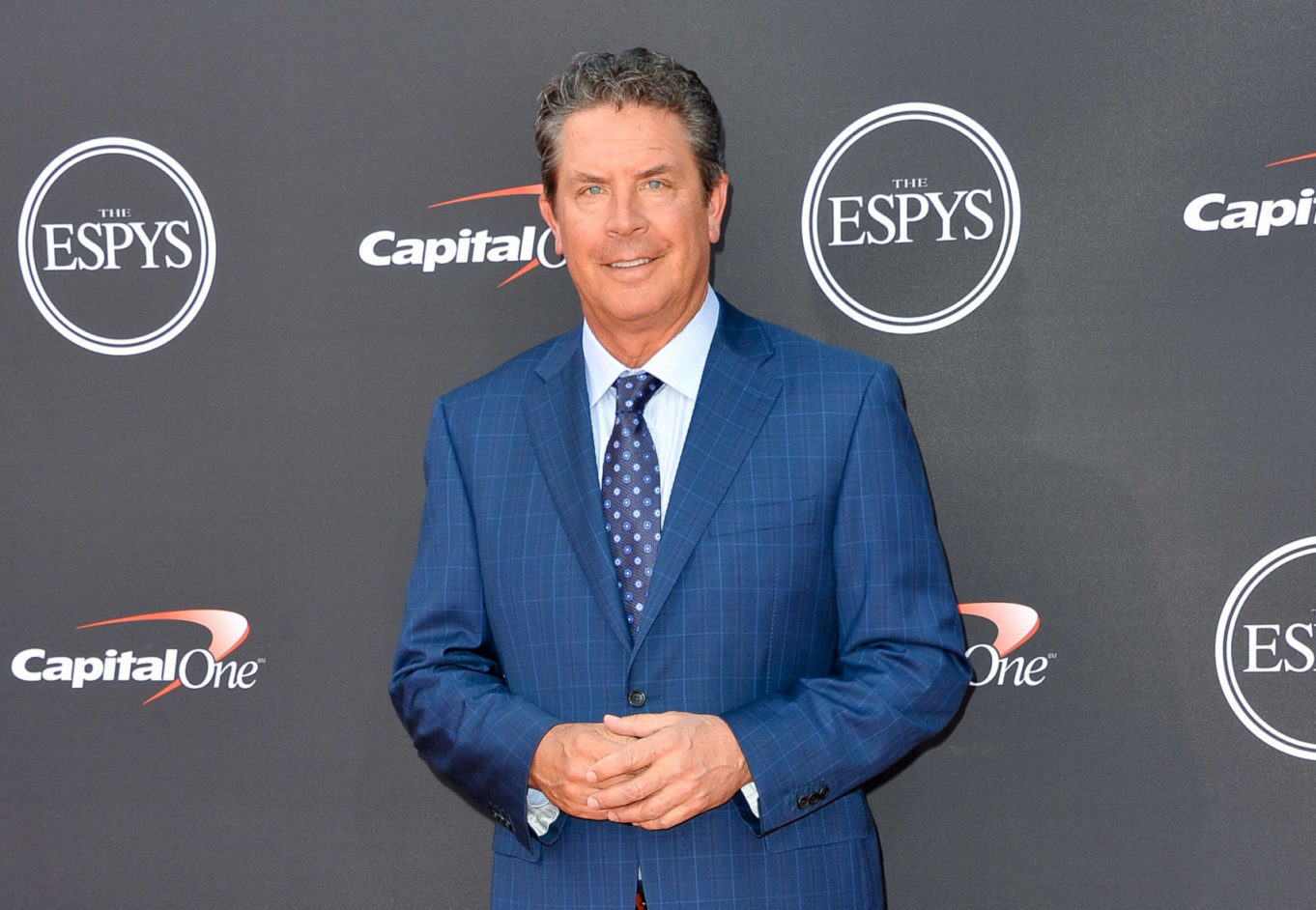

Featured image: Dan Marino attends The 2018 ESPYS at Microsoft Theater on July 18, 2018, in Los Angeles. (Photo by Allen Berezovsky/FilmMagic)

Talking Football

It wouldn’t be an interview with Dan Marino without questions related to the sport that made No. 13 famous in South Florida.

On Coach Don Shula’s death in May: “I actually spent a lot of time with him over the last couple years at alumni functions or [charity events] where we worked together. He’s going to be missed. He was a superstar. And he was really special to me as a young man, not only by the example he set, but also how he trusted me at 21 to take charge of his offense. Overall, we spent like 13 seasons together. I used to joke with Claire that I spent more time with Coach Shula than I did with her in those days.”

On seeing Tom Brady play into his 40s and wondering if he should have played longer: “I think about that a lot. I probably could have, and I didn’t. Probably because I felt like I was going to just be a Dolphin forever. But I could have played a couple more years. … The rules have changed now, and, healthwise, guys take care of their bodies differently than we did 20 years ago. So, they’re going to be able to play a little longer. It’s great. I love what they’re doing.”

Dan Marino Campus Specialty Plate

Dan Marino Campus Specialty Plate

As part of its ongoing fundraising efforts, the Dan Marino Foundation has launched a license plate that features the former Miami Dolphins quarterback in action. The foundation must secure a minimum 3,000 vouchers before sales, per Florida Department of Highway Safety and Motor Vehicles guidelines, to manufacture the specialty plate. The first 1,000 people who order the voucher will be entered into a drawing; 10 people will be randomly selected to receive a football signed by the Hall of Famer.

The Foundation wants to spread the proceeds connected to the annual use fees for a specialty plate across a variety of needs facing young adults with developmental disabilities, including the purchase of technology like computer eye trackers for students with degenerative diseases that severely limit the use of their arms and hands.

“Another example is transportation,” says Mary Partin, CEO of the Foundation. “Less than 11 percent of our students drive. We have kids who get a job at [a restaurant], and they may work until midnight. But there’s no public transportation for them at that time of night. So, we’re able to supply dollars for them to Uber home.”

Advance-sale vouchers are available at marinocampuslicenseplate.com (South Florida Ford dealers everywhere also are promoting the plate).