The nation has reached a crossroads.

The nation has reached a crossroads.

Revolution is still in the air. Fierce tribalism stains our discourse. We’re in debt to other countries. And the specter of disease is never far from our thoughts.

Fortunately, for the United States, the presidency is in the best possible hands. That’s because the year is 1789. And George Washington has a plan.

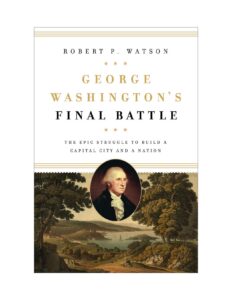

Part of that plan, as chronicled by Robert Watson in his latest work, George Washington’s Final Battle, involves the push by our country’s first president to establish a capital city on the Potomac—a project that the famed commander in chief of the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War intuitively sensed could help bridge divides and infuse our fledgling democracy with a sense of national pride.

But it wasn’t easy. As the distinguished professor of American history at Lynn University submits, the epic struggle to bring the capital city to fruition drew on a variety of skills not always associated with depictions of Washington.

In scenes throughout the book, Watson brings to life Washington’s gifts as a master of theatrics, someone who would stage dramatic moments for maximum effect on those in the room; and as a savvy politician who knew how to lobby and, when necessary, exert pressure to flip votes. Most impressively, Washington has foresight that other founders—like Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton—fail to have about the importance of a capital city.

It’s also a story that, for obvious reasons, resonates with the modern-day battles being waged in our government. Though Watson penned the book—he’s written more than 40 during his prolific career as an author—before the storming of the Capitol, he has plenty to say about that incident as well as another current phenomenon for which Washington has become a lightning rod.

What piqued your interest about Washington’s push for a capital city—and what does it reveal about him that might surprise people?

There were sides of Washington’s personality that I’ve always felt that history has largely missed. We see Washington monolithically, as this stoic image. He’s more monument than man; he’s more myth than flesh and blood. He doesn’t say much. He’s a big man; he stands there, he has his sword, and he’s going to let that do the talking.

But what we miss in the depiction is that Washington was a visionary.

Of all the framers, Washington is the one who’s not well-read, not well-traveled, and not well-educated. He was the only one who had calluses on his hands from living outside, fighting Indians, surveying and farming. He also doesn’t have the military training. He loses more battles than he wins. He’s making it up as he goes along through the Revolutionary War. He has to be creative. He has to hit and run. He has to use guerrilla tactics.

So, Washington was able to think outside the box. As a result, he connects the dots when the other founders don’t. He understands, for starters, that our government is weak and [in debt; several European countries floated loans to the United States during the war]. It could still collapse. Second, we have no credibility in the eyes of Europe; we’re backwater frontiersmen to them. For us to trade and work with Europe, we need to be seen as serious. Third, we have a North and South rift that’s already bitter. And fourth, there’s no spirit of Americanism yet. People identify with their respective states.

How do we resolve these problems? We build a great, glorious capital city. We locate it halfway between the North and South; it looks like Rome, and it’s bigger than Paris and London. We get credibility in the eyes of Europe. We unite the North and South. The government now becomes legitimate and strong.

What a vision—and Washington [creates it] out of nothing. We literally hack the capital city out of the woods.

How important is the architecture and landscape of the capital city when it comes to reflecting the ideals of Americanism?

Washington understood the politics of architecture. For example, he wanted the Capitol and the president’s house to be [on opposite ends of Pennsylvania Avenue] to symbolize the separation of powers.

Washington finds Pierre L’Enfant, who was in the Revolutionary War, so they knew one another. L’Enfant was classically trained as an engineer and architect—and he was great on the battlefield. He’s also a megalomaniac. But Washington knows that L’Enfant’s vision is his vision. L’Enfant is ultimately fired from the project, but his original design is really the city today. Grand boulevards that intersect at angles. Monuments and memorials. He hired Scottish stonemasons to add embellishments to the White House. It gives it this feel of Rome, or the Acropolis in Athens.

It’s all symbolic. And it’s meant to imbue the people with a sense of national pride. I don’t think John Adams or Alexander Hamilton or Ben Franklin understood the politics of architecture. Washington did. And it’s genius.

As you were planning to write this book, did you consider how it might resonate amid our political climate?

When I started the book, I was aware that the argument over the capital city would resonate and have legitimacy today. I’ve stood by this my whole career: Of course, we’re objective. And of course, historians follow the facts. But if I spend every day for a year reading diaries, researching [and living with the material], I feel I’ve earned the right to advocate a little bit. Not grotesque partisan advocacy, but advocacy in that I want people to read the book on both sides of the political aisle and go, “We’re being tribal, we’re being partisan, and look what happened back then.”

In this book, I tried to draw parallels. There were several cases, over the debates on the capital city, where the South literally said: We will not compromise, and we will walk out if we don’t get the capital. Here we were, trying to build a nation. We had fought a war. Soldiers had died. And people were really going to say, I refuse to sit down with you and cooperate? I hit that hard, because to me it sounds like Ted Cruz and AOC [Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez]. It sounds like Marco Rubio and Bernie Sanders.

I also wanted people to understand that we should all be proud of our capital city—the tree-lined mall, the museums, the touching memorials. That should be something that we can all unite behind.

As someone who lived with this material for as long as you did, and who understands everything that went into creating the capital city, how did the events of Jan. 6 hit you personally?

I’m still not over it. You know when something happens in your life, and you feel like you’re kicked in the stomach? Like when you lose a friend?

Watching Jan. 6 unfold made me sick, but I couldn’t stop watching it.

For one, I love the capital city. I’m nerdy about it. I taught at Georgetown. My son is a junior at American University. [In pre-COVID times] I’d go to D.C. several times a year to visit the Library of Congress and National Archives to do my work.

Second, this is what I do for a living. [With this book], I lived with [the story of Washington and the capital city] for a year, every day. It was devastating to think of the U.S. Capitol, this temple of liberty and democracy, being [overrun]. It’s majestic, and it embodies who we are.

I remember calling my son that day. I’m a pretty chill person. But I told him that if I were in Congress, or if I were one of the aides, I wouldn’t have left the congressional chambers. I would have broken off one of the table legs, and I would’ve stood my ground.

That’s my building. I would have barricaded the door, and the first person with horns on his head and a Confederate flag, they would have gotten it over the head. That’s not being blustery. That’s what it means to me.

In the subsequent weeks, we’ve seen more disturbing information come out. We’ve seen people dismiss it, and we’ve seen people politicize it. To me, it’s still a fresh, open wound.

How do you reconcile Washington’s importance to the American experiment with a cancel culture that takes issue with the fact that he owned slaves?

On the one hand, the cardinal rule in history is you don’t take a 2021 mindset and apply it to 1776. It’s like taking an American mindset and applying it to France or Nigeria or Argentina. It’s square pegs in a round hole.

That said, there are certain things—genocide, murder, slavery—that transcend the centuries. And they’re bad no matter when, no matter where, no matter what.

Regarding the cancel culture, if a CEO says something blatantly racist, blatantly antisemitic, they should resign. It’s going to be a distraction for the organization, and they’re in a position of responsibility. As a professor, if I spew homophobia and racism in the classroom, I shouldn’t be in front of impressionable 19-year-olds. But if the local plumber or the local baker says something, I don’t care. I don’t want the cancel culture to go that way. And I don’t want it to be knee-jerk.

With Washington, we need to look at things in their entirety. If you look at winning the revolution, creating a nation, preserving our democracy damn-near single-handedly … Yes, slavery is unforgivable. But, we’d be drinking tea today if it weren’t for George Washington.